The Soul of Dunhuang Murals

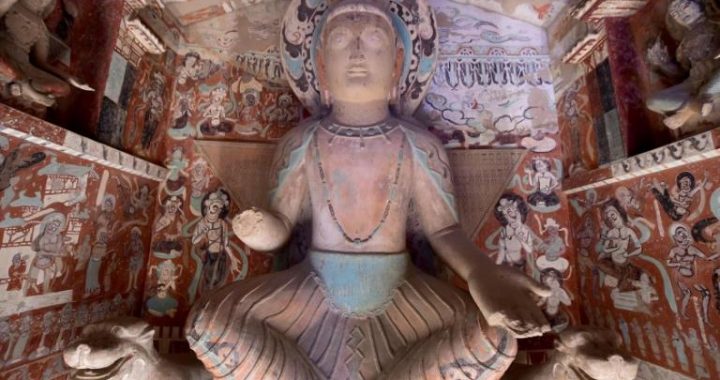

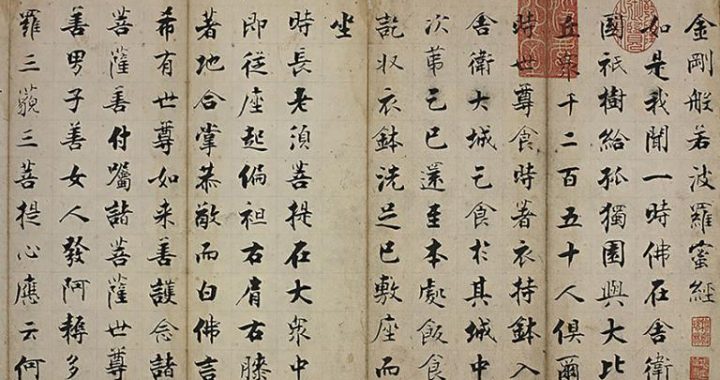

9 min readIn the murals of Dunhuang, flying apsaras can be regarded as the most colorful and dynamic. They are called “the soul of Dunhuang murals.”In Sanskrit, apsara is Gandharva, also named the gods of fragrance and music. It is one of the eight classes of supernatural being who appear in pictures of sermons accompanied by celestial symphony and dancing flowers. The huge variety of flying apsaras are definitely the product of Chinese Buddhism and are called as a whole “celestial singers and dancers.”

A1l ancient civilizations had their own image of a flying deity. In Greek civilization, it is angels, boys or girls with wings on the arms. In ancient China, we had feathered man, with feathers on his arms that enable him to fly; therefore i is also called flying immortal. In India they had both haloed figures on clouds and double-winged angels. The flying apsaras of Dunhuang are borrowed from India. When apsaras entered grottoes in Qiuci, they became clumsy short figures with round faceand beautiful eyes, and remained bare-footed and naked above the waist, with Persian scarf but without cloud, thus the special style of the Western Regions was formed.

After arriving at Dunhuang, they blended gradually with feathered men and were transformed gradually by the end of the 5th century into flying immortals with an oblong face, long brows, small eyes, hair coiled up into a bun, bare above the waist, long scarves draping over shoulders, haloless, graceful and flying with clouds. And this is the Dunhuang style Chinese apsaras.

The painting of flying apsaras started in the Sixteen States and did not stopuntil the Yuan dynasty.A number of over 6,000 have been preserved now. In over 1,000 years’ history, there had been constant variations in carriage, conception, style, and taste due to the replacement of dynasties, the transfer of power, the flourishing of economic development, and the frequent communication between Chinese and Western Regions cultures. Artists of different times created flying apsaras of different stylistic features.

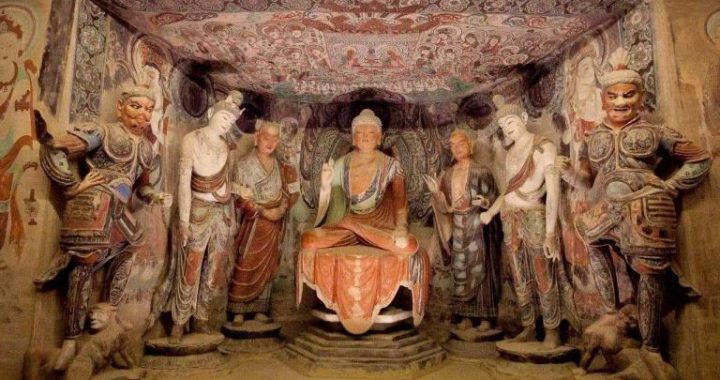

In the period of approximately 170 years (366-535) from the Northern Liang of the Sixteen States to the Northern Wei, the flying apsaras were deeply influenced b the style of India and the Western Regions: tubby in stature, half naked above the waist, wearing long skirts,a ribbon winding over both arms, either with palms put together or in a gesture of scattering flowers, stiff in V-or U-shaped body, similar to the early apsaras in the grottoes of India and Qiuci, Xinjiang in mould, countenance, posture, coloring, and painting technique. Discoloration resulting fromthe technique of shading turned the nose bridges and pupils white. Current extant caves of the Northern Liang at the Mogao Grottoes are only three in number; the fewflying apsaras typical of the Northern Liang style are found in the jatakas on the north wall of Cave 275.

The flying apsaras in the Northern Wei period basically keep their features of the Western Regions with some obvious changes in the direction of sinicization. They are taller in stature with some having legs twice as long as the torso, the ribbons are longer with their ends becoming sharp angles so that the crudity caused by stiff joints is hidden; nevertheless, they still lack flexibility in spite of the added energy. Flying apsaras in this period are characterized by one leg striding forward while the other turning up from behind and thus look exaggerated and rich in pleasing qualities. As Dunhuang was less restrained by the Central Plains, being far away from it, but more influenced by the proximity to the Western Regions,a fewflying apsaras are nudes, and this adds to the charm of murals. The most typical cases of the Northern Wei style are the pair apsaras above the story painting on the north wall of Cave 254 and another pair over the picture of sermon in the rear section of north wall in Cave 260.

Dunhuang apsaras in the 80-odd years (535-618) from the Western Wei to Sui experienced mutual integration of the Buddhist devas with the Taoist featheredbeings and the apsaras of the Western Regions with the flying immortals of the Central Plains as well as innovation, so the works in this period are the combination of Chinese and Western Regions elements. Flying apsaras in the style of the Western Regions inherited the style of mould and painting of the Northern Wei whose representative work can be found in the quadruple apsaras in the upper part of niche on the west wall of Cave 249, while flying apsaras in the style of the Central Plains came into existence when Yuan Rong,a member of the imperial clan, became governor of Guazhou(present-day Dunhuang).

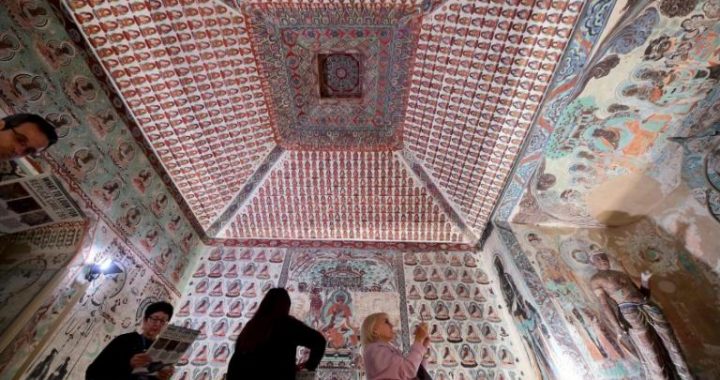

They are painted by means of line drawing of the Central Plains without the application of shading of the Western Regions so that the figures appear slim andhandsome with loose robes and exquisite ribbons and their gestures seem light and gracefu1. On the ceiling of Cave 249, King Father of the East and Queen Mother of the West, traditional Chinese figures in fairy tales, share the same grotto with the Buddhist Asura, the traditional Chinese Scarlet Bird and Black Turtle fly side by side with the Buddhist apsaras, vajra-warriors, so that no one can tell which are the Indian deities and which are the Chinese immortals. Buddhism gave full play tits advantage of compatibility and gradually integrated with traditional Chinese culture in order to be adjusted to the fresh cultural environment, while Chinese culture also borrowed the Buddhist art and progressed in the direction of perfection. The most representative work of it is the dozen of flying apsaras in the upper part of south wall in Cave 285.

The Northern Zhou was a minority national regime set up by the Xianbei in the northwest. Though short-lived, it constructed many caves at Mogao. The Xianbei rulers believed in Buddhism and had friendly relations with the Western Regions. The flying apsaras of both styles gradually intermingled and the effect was straightforward and appeared lively and rhythmic with the reflection of solid color background.A novel approach of shading was formed in this period, the style of theCentral Plains, namely a gradual change of value from a center outward, unlike thatof the Western Regions in exactly the opposite direction. During this period,a lot of music and dance apsaras appeared, playing various musical instruments while flying toward the Buddha. An effect of motion and adornment was realized by changing the colors of dress and ribbons. The most typical cases are found in Cave 290 and Cave 428.

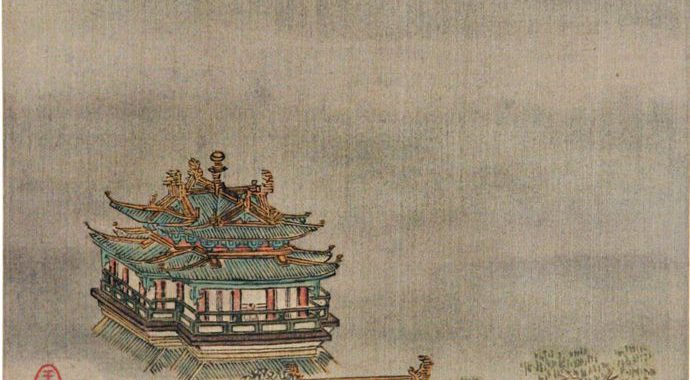

The Sui emperors were fond of flying apsaras. For this reason, paintings of this subject reached its climax. They were painted on ceilings and walls, and in niches and sermons. Groups of apsaras soar freely in different poses and with different expressions. Music and dance apsaras in celestial palaces and pavilions soar high into the air and hover around a cave. Some are in the style of the Western Regions, some in that of the Central Plains, while others reflect the combination of both.

The painters were in total command of representational skills of flying apsaras sothat they could treat different cases and various forms as they chose. Some apsaras are full round in feature, while others are delicate and pretty. Some of them are strong and others slender. Some wear sleeveless short skirts, and others wear longskirts with broad sleeves. Some are with coronet on the head, and others tie their hair into a knot. Once in a while, apsaras in the form of a monk is also found. Theysoar in various manners but all appear free and relaxed. Some spring up; others fal down. Some fly with the wind while others against it. Some soar singly, and others in groups. On the whole, the painting of flying apsaras served as a link between past and future; it was a period of communication, integration, exploration and innovation with the general tendency of sinicization and had laid the foundation for the complete Chinese style of flying apsaras in the Tang dynasty. The most typical case in this period can be found in Cave 427 and Cave 404.

The Tang dynasty witnessed the height of splendors of apsaras in Dunhuang whose artistic image reached the stage of maturation and perfection. The Tang is a dynasty in which large-scale sutra illustrations, an element of which being apsaras, are found the most in quantity and occupying almost all walls of the Mogao caves buil in this period. In these sutra illustrations, flying apsaras usually attend sermons, scattering flowers, singing and dancing, worshipping, and paying their respect; or they add to the joy of the Buddhist world of Western and Oriental Pure Lands. They hover over the head of the Buddha or over the realm of pure land. Some land slowly on colorful clouds, while others raise their heads and arms and spring up. Some fling into the air with fresh flowers in their hands, and others soar across holding flower trays. The apsaras are wingless, and for flight they do not depend on clouds but on their fluttering robes, skirts and ribbons, just as described in the great Tang poet Li Bai’s ode to flying immortal:”With lotus flowers in hands they walklightly in the Heaven; with colorful skirts dragging broad ribbons they soar up.”

The most typical works of the earlier days of the Tang are the pair apsaras in Cave 321 of the early-Tang and the quadruple apsaras in Cave 320 of the high-Tang periods. Whether collectively or individually, apsaras in this period are fully represented as clever and lively young ladies. Every twinkle and smile and every action cannot but show their natural simplicity and youthful vigor.

By the late-Tang period, beautiful human figures became plump. And flying apsaras now also grew short of the previous spirit of progress in motion and mood of freedom and joy in posture. In its place were grace, elegance and dignity reflected by maturity and lightness and relaxation in movement; however, immodest expression of solemnity results in the lack of energy. The artistic mould of dress and adornment was shifted from gorgeousness to simplicity, and their expression was no longer stimulated and joyful but calm and sad. The most representative work of this period is the flying apsaras above the Illustration of the Nirvana Sutra on the west wall of Cave 158 of the mid-Tang period. They soar around the bodhi tree canopy, some holding flower trays, some holding jewels, some holding censers, others playing flutes, or scattering flowers, or worshipping toward the Buddha. They are quiet in expression and slow in movement. There is no sense of joy; instead, there is rather an appearance of sorrow revealed in the solemn expression. It is a religious state of mind of shared sorrow between the divine and the mortal.

In the 460 or more years (907-1368) from the Five Dynasties to the Yuan, the painting of apsaras in Dunhuang inherited the flavor of the Tang style. There was n innovation dynamically or uniqueness in emotional expressions and the developmentwas toward formulization. This is the period of decline for the painting of flying apsaras in Dunhuang. In the Five Dynasties and Northern Song, Dunhuang was under the control of the Cao’s Return-to-Allegiance Army Regime in Hexi. The Caos took theirfaith in Buddhism and, therefore, built a large number of caves at Mogao and Yulin, renovated many others, established art academy and employed some well-known painters then, so the murals were relatively uniform in style. However, without the powerful cultural influence of the Central Plains, these paintings evidently showed the tendency of conservatism and decline.

Representative works can be found in Cave 16 of the Yulin Grottoes and Cave 327 of the Mogao Grottoes. Apsaras of the Mogao Grottoes in the Western Xia are characterized by the integration of Tangut human features and folk customs,a representative case is found in the boy apsara in Cave 97. In the Yuan dynasty, the Mongolians ruled Dunhuang, but they built or renovated few caves at Mogao and Yulin.

Esoteric Buddhism was popular in this period. It was divided into two sects: the Tibetan and the Han. In the Tibetan tradition of Esoteric Buddhism, there is no apsara; while in the Han tradition, not many are found. The most representative works in this context are found in the four apsaras above the Illustration of Thousand-Armed Thousand-Eyed Avalokitesvara Sutra on the north and south walls of Cave 3, particularly the pair on the north wall, which are ideal in mould with solemn facial expression and realistic depiction. However, they are short and childlike with round face and appear incapable of flight.

Dunhuang apsaras have experienced over 1,000 years’ history and demonstrated the features of different times and various national styles. Many graceful images, joyful realms and permanent life force of art are still appealing. As is pointed out in”Apsaras in Human World”by Duan Wenjie, late President of Dunhuang Academy,

“They did not die with their times. They still survive, living in new songs and dances, murals, trademarks, advertisements, or everywhere. It should be said that they have come down to the human world from the celestial kingdom, living in our hearts and constantly revealing to us enlightenment and enjoyment of beauty.”