The story of Dunhuang painting wall

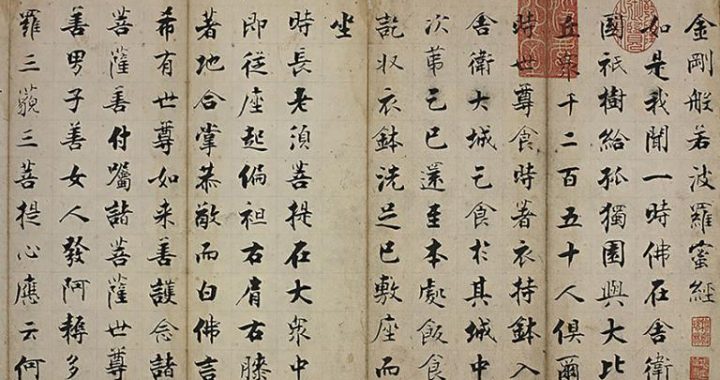

6 min readAmong the large number of economic documents unearthed from the Library Cave, there are many stories of social life in the Tang and Five Dynasties Dunhuang.P.3257,a document of civil law in the reign of Cao Yuanzhong of the Return-to-Allegiance Army Regime, shows us a lawsuit for land ownership.

On a certain day of the twelfth month of 945(the 2nd year of Kaiyun of the Later Jin), to support herself,a widow named Ah Long filed her complaint directly to Cao Yuanzhong, governor of Shazhou, against Suo Fonu for the 22 mu of land the latter had occupied for over ten years. On the 17th day of the same month, Cao Yuanzhong referred the case to an officer named Wang Wentong to carry out investigations.

Soon Wang found out the details: Ah Long’s son Suo Yicheng was exiled to Guazhou on the 19th day of the third lunar month over ten years before because of an offence. They had had 22 mu of ancestral land granted according to the number offamily members. Suo Yicheng contracted the land to his uncle Suo Huaiyi with the condition that the latter get all the harvest but pay the required tax on land and undertake related corvee. Another clansman Suo Jinjun settled in his childhood atNanshan among the nomadic Tuyuhun tribes and he was not taken into considerationwhen the family was broken up and their property had been divided. Not long afterSuo Yicheng’s exile, Suo Jinjun returned to Shazhou with two horses he had stolen from Nanshan and was rewarded by the Return-to-Allegiance Army Regime for one of th horse given to the government. He settled himself and applied for his share of land and the government determined for him to take over 22 mu of the total land contracted to Suo Huaiyi who had gone herding horses for the government and was not informed of the matter. He did not claim the land since it was not his from the ver beginning. Therefore, Ah Long intended to go to the local authorities to argue for the land ownership, but considering that she was a family member of a criminal, she did not do so for fear of being reprimanded.

Having long been among the Nanshan tribes and being poor at farming, Suo Jinjun could not endure the hardship at Dunhuang and went back to Nanshan several months later. His land was succeeded by his nephew Suo Fonu. Now, Suo Yicheng died in Guazhou. Ah Long was old and her grandson Suo Xingtong was still very young. They went begging and depended on each other for survival. Therefore, Ah Long handed up her letter of complaint and claimed the land of 22 mu.

After investigation and evidence collecting, Wang Wentong submitted to Commissioner Cao the following 5 files: Ah Long’s petition, rent contract betweenSuo Yicheng and Suo Huaiyi, and the notes of inquisition of Suo Fonu, Ah Long and Suo Huaiyi. On the 22nd day of the 12th month the same year, the commissioner gave his verdict which maintained the previous official solution and meanwhile showed his concern over the weak: the land which had been given to Suo Jinjun was not to be claimed, but since Suo Jinjun had gone back to Nanshan, Ah Long and her grandson would enjoy the right of land use and harvest. For such a common civil dispute over landownership, the trial underwent a complete series of procedures: lodging a complaint, placing on file for investigation, carrying out investigation and collecting evidence, judgment, and settlement and was given close attention by the commissioner, and it can be seen that the economic life and social stability in Dunhuang was intimately related.

The mode of investigation and evidence collecting in this case is worthy ofattention. It is similar to the trial of civil cases in modern times, namely, chiefly by means of inquiry of the parties concerned. In this case, both written evidence(rent contract) and interested parties were available. All statements were signed, so that a complete system of evidence was constituted. The legal system reflected in this contract, including the system of land, evidence, and the power of contract, has provided us with proof in comprehensively understanding traditional Chinese culture of law and deeply experience its characteristics.

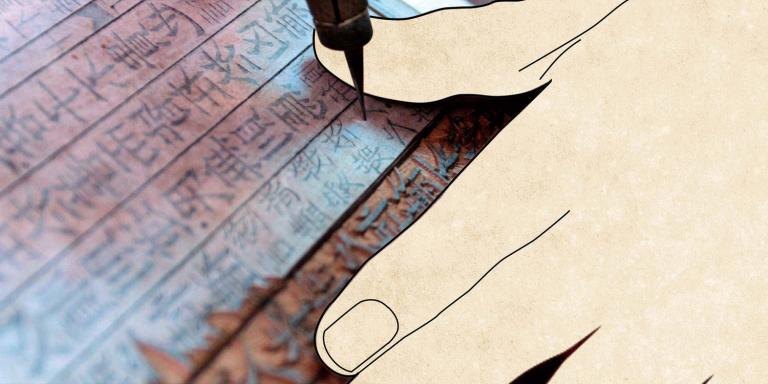

The main body of law in the Tang dynasty is composed of lu(law), ling (decree), ge (regulation) and shi (rule), of which only Tang dynasty li and ltishu (annotation on law) are completely preserved to this day, and the other types were lost after the Song dynasty. Therefore, the Dunhuang manuscripts, though fragmentary, have provided precious data for us to understand the true appearance oi legal documents of the Tang, and important materials of reference for the compilation of the other formats of legal documents of this period. For example, Kaiyuan Shui Bu Shi (Rules for Bureau of Waterways and Irregation in the Reign of Kaiyuan) prescribed detailedly rules of administration of water channels and bridges and the relevant responsibilities of governments of all levels. It has offered precious data for the understanding of the administrative system of water conservancy in the Tang and made up for the insufficiency of records contained in Tang Liu Dian (Six Institutions of Tang Dynasty, New History of Tang Dynasty and 01d History of Tang Dynasty. Meanwhile, it enables us to have a specific understanding of the content and form of shi and offers us templates with which we can search for other items of the same genre.

There are over 300 documents similar to the contract of Houjin Kaiyun Er Nian (945) Shi’ er Yue Hexi Guiyijun Zuo Mabu Yaya Wang Wentong Tongdie Ji Youguan Wenshu (Certificates and Official Documents by Wang Wentong, Official of the Hexi Return-to-Allegiance Army in the 12th Month of the Second Year of Kaiyun (945), Later Jin Dynasty)(P.3257) with very rich content, including contracts of business deals, loans, employment, tenancy and mortgage, voucher, certificate of family division, and certificate of divorce. They were mostly used contracts with real names. They are first-hand data reflecting the contemporary social and economic conditions and are therefore of irreplaceable value for the understanding of the economic conditions of ancient China.

Economic documents in the Dunhuang manuscripts also include shoushi(household report), account, household register, chaikebu(corvee registration), the most important first-hand data for the study of ancient land system and economicrelations. In the Tang dynasty, every household had to faithfully declare its population, land area, location of habitation, and other information, which were collected by villages and neighborhoods who reported to their prefectures and counties. These documents are termed shoushi. Basing on these documents, local authorities compiled household registers once every three years. Both shoushi and registers recorded much more complicated information than the current householdregisters, so they are of important value to the research of ancient population, land and corvee systems.

Chaikebu was account designed by a county to record corvees, which were examined and checked by the county magistrate and used as basis to dispatch official services. Examples in the Dunhuang manuscripts are Tang Tianbao Nian Jian Dunhuang Jun Dunhuang Xian Chaikebu(Corvee Registration of Dunhuang County, Dunhuang Prefecture in the Years of Tianbao, Tang Dynasty) and Tang Dali Nian Jian Shazhou Dunhuang Xian Chaikebu (Corvee Registration of Dunhuang County, Shazhou Prefecture in the Years of Dali, Tang Dynasty), compiled according to villages, the first section of which records those who were dead or absent, and the second section consists of those present, their name, age, identity, and services they had fulfilled. The discovery of these documents provided very important data for the study of corvee in the Tang dynasty.