Shangri-La’s mountain village

14 min readMost people in nothwest Yuan live in smal villges that semingy Like most mountain people in the world, they live in enduring poverty resulting from a combination of low natural productivity and centuries of economic and political marginalization. As poor villagers, they spend most of their time subsisting-procuring the basic necessities of shelter, food, and energy-with little time or opportunity to generate cash income.

In this article we look primarily at shelter and food, aspects of village culture that can be easily observed in repeated images.From these photographs we can infer changes in human population and food production, as well as the addition of modern infrastructure to village development. Many aspects of culture often are not observable by repeat photography because there are no direct visual indicators.I have been lucky in a few instances, however, and include here two sets of photographs that indirectly illustrate shifting ethnic dominance and the persistence of marriage customs during the past century.From a broad perspective, the photographs illustrate cultural adaptations made by the different ethnic groups for survival in a Himalayan landscape.

Unlike contemporary photography, however, repeat photography allows us to explore how these adaptations have persisted both in space and time.For example, some groups have carved out a relatively comfortable niche in the lowlands, such as the Bai people, who have been and still are valley rice farmers. At the other extreme are the Lisu and Yi, who have adapted to life higher in the mountains, braving considerably more marginal conditions in which to make a living.One unusual adaptation is the Tibetan custom of polyandrous marriage, still common in Deqin County. As practiced in Yunnan, two or more brothers are married to one woman. This is not a quaint cultural holdoverfrom a bygone era. Polyandry successfully minimizes land subdivision in alandscape where arable land is at a premium and resources are scarce. One family of brothers, along with their wife, maintains the inherited family holdings without dividing the land base and building more houses.

Evidently this custom, while phased out in many areas, is still advantageous to the Tibetan lifestyle.It is well known that the population of China has mushroomed during the past century. Population change across rural Yunnan is difficult to establish, but in Deqin County it has increased at least four-fold since the1920s. How has a growing population manifested itself in the villages? The single best visual clue is the change in the number of houses. All photo setsshow an increase in village population, even with the prevalence of polyandry in Tibetan areas. Nearly all population growth is from within the village itself, that is, it is not due to immigration or from outside investment.

More striking is the widespread abandonment of non-irrigated crop fields on steep mountain slopes,a process that began more than 50 years ago. It appears then, that villagers are producing more food onless land, perhaps as a result of improvements in crop varieties and farming techniques.Rephotographing village scenes was the most enjoyable aspect of this project. Many villages, once on a main caravan trail, are now off the beaten track, having been bypassed by modern transportation routes. While theymay have seen a few outsiders in the 1930s, today’s residents of Okolo were stunned when we entered their village in April 2003. The elementary school let out class so that children could take in the excitement. Okolo is a Lisu village perched 300 meters (1000 feet) above the Nu River. In the early 20th century most villages in the Nu valley occupied these mid-mountain positions, as the valley bottoms were uninhabitable due to malaria and excessive heat. Herein lies the power of repeat photography to providea factual historical profile.

The modern perception is that these mountain villages have recently been established, are environmentally destructive, and should be relocated to the valley or distant urban centers. The historical record shows that the opposite is true.C.P. FitzGerald left his base in Dali during the winter of 1937-1938on a journey to Tibet. He followed the main caravan route north to the town of Weixi where he was prevented from going further by Lisu bandit activity. Along the way, he photographed this scene from the town of Shigu, a popular stage stop along the route.A building now occupies FitzGerald’s original camera point. We had to move a little to the right, giving a slightly different perspective on this valley full of late winter crops of small grain and rape. The fields became flooded and rice was planted in the summer.A careful look at the valley bottomreveals that the irrigation and crop field patterns are identical in both photos. They remained remarkably stable for 67 years, despite radically varied tenure systems that ranged from communal management to private household responsibility. What did change is the floodplain of the Chongjiang River, flowing through the valley on the right side of the images. The river channel has been straightened and channelized, reducing the floodplain along with the attendant water-holding capacity and species diversity that require an unconstrained river. By this action, Shigu farmers participated in an agricultural practice that was common in riparian landscapes throughout the world during the 20th century.Joseph Rock took the original photograph in the middle of May, just as opium was being harvested from mature poppy fruits. The British introduced opium to China after the Second Opium War(1856-1858), forcing China to legalize its import. They sold opium from India and bought tea from China to bring back to Britain. When the British figured out how to grow tea in India and stopped opium imports to China, local cultivation of opium commenced for the now-addicted population. It was estimated that in 1879, one-third of Yunnan’s arable land was given to opium poppies as a winter crop.

By the 1920s, the government had outlawed opium growing throughout China. In reality, however, independent warlords (called “governors”)controlled many of the outlying provinces and selectively enforced laws as they saw fit. The governor of Yunnan derived most of his income from opium sales, so rather than enforcing the ban, he unofficially encouraged production. Folowing the communist triumph in 1949, the nationwide ban on opium production was enforced and today wheat, pictured in the modern scene, and other food crops have replaced poppies.The Yunnan Plateau is an extensive rolling upland in central Yunnan.Tectonic forces in the underlying limestone created many lakes, including the one pictured here. Lashi Lake lies within an internally drained basin. Water flows in from surrounding mountains and drains out through a subterranean sinkhole on the far side of the valley. In Rock’s day, the lake level fluctuated wildly from what you see in his photo, taken during high water at the endof the monsoons, to nearly empty during the dry season. Several years in a row of low rainfall allowed the villagers to completely reclaim the basin forcrops, as it was in 1934 when Rock saw it again. Today, the lake level is stable throughout the year, controlled by a low dam that prevents outflow from reaching the sump.

The stable lake level ensures that water can be deliveredthrough a tunnel to Lijiang city, helping drive the frenzied growth of this global tourist destination.The small village of Yuhu rose to worldwide prominence in the early20th century as a center of biological exploration. Towering nearby is Yulong Snow Mountain, the first peak of the Himalayas when approached from the east. The name Yuhu is relatively new. Naxi and Western explorers knew the village as Ngu-lu-ko, referring to its position at the”foot of the silverrocks range,”with silver here referring to the snowy glaciers of Yulong Snow Mountain.With a combination of relatively easy access and biological richness, Yulong became a magnet for foreign scientific expeditions, and Yuhu was their headquarters. The Scottish plant collector George Forrest began this legacy in 1905 and used Yuhu as his base for seven expeditions until his death in Yunnan in 1932. Forrest trained many villagers as guides and fieldcollectors used by subsequent explorers. Expeditions were especially common in 1914to 1916. In addition to Forrest, Yuhu hosted the Austrian botanists,Heinrich Handel-Mazzetti and Camillo Schneider, as well as zoologist Roy Chapman Andrews from the American Museum of Natural History. Frank Kingdon-Ward also passed through Yuhu at various times. Last in this prestigious lineup was American botanist Joseph Rock, who periodically lived in Yuhu from 1922 to 1949, at which time communist authorities expelled him.As seen in the 1929 photo, Yuhu was a small village with one set of houses flanking the main street(see also the next set of photographs).Today it appears to have more than quadrupled in size.

Standing out on the left side of the 1929 photograph is a dark grove of pine trees associated with a Buddhist temple. The temple became a school during the Cultural Revolution and was later destroyed.A few dying trees are all that remain of this sacred grove.This scene captures the interior and main street through the oldest partof Yuhu. The 2003 photograph shows Yuhu as a typical modern Naxi village, where electricity and motor vehicle access are now embedded within the traditional village layout. Like so many agricultural practices, however, water distribution has remained the same. The open canal on the right side of the dirt path in 1929 is in the same place in 2003, now running through a concrete trench.There was no major trade route up the Nu River valley in the early20th century. The area was under nominal control of the Chinese, and each village was in conflict with its neighbors to the point at which trails were not maintained between setlements. These were the conditions under which Andre Guibaut and Louis Liotard struggled up the Nu valley during the summer of 1936, passing through the mountainside village of Okolo. We did not find the exact photo point of Guibaut and Liotard, but were able to capture the same general area in our modern retake.The few large crop fields seen in 1936 have clearly been subdivided into smaller units and have expanded into surrounding shrublands.

Not surprisingly, the number of houses has nearly doubled, indicating that thehuman population is much larger today. Interestingly, house construction has changed little. Houses are still largely made of bamboo, especially for structural beams and as woven mats for walls and floors. In fact, Guibaut and Liotard used this photograph to illustrate bamboo cultivation by the Lisu, seen as large plumes in both old and new images. Grass thatch is still the most common roofing material, although some households with higher cash incomes now use corrugated panels as roofs.Then, as now, corn was the primary crop in Okolo fields.A species native to Mexico, corn was introduced to China through Yunnan in the mid-16th century, where it quickly became a staple of mountain tribes. Considering this was less than 100 years from its discovery by Europeans, the speed with which corn reached eastern Asia is rather spectacular. Corn and potatoes, another New World crop, allowed cultivation in mountains as never could have been done with rice. Land cleared for these crops led to substantial increases in deforestation recorded in 17th century Yunnan.Their native lands are confined to the Nu River valley where they are sandwiched between Tibetans on the north and east, Lisu downriver to the south, and the even rarer Dulong people to the east. Add to that a smattering of Han and Naxi who live in the area and you get an extraordinary ethnic mix of people with different values, languages, customs, land use practices, and religions.Although individual villages tend to be ethnically homogeneous, the broader cultural mosaic of the Nu valley is shifting over time. Rock’s 1923portrait is of the Nu village leader of Chala. The modern retake is of our Tibetan guide from the nearby village of Baihanluo.

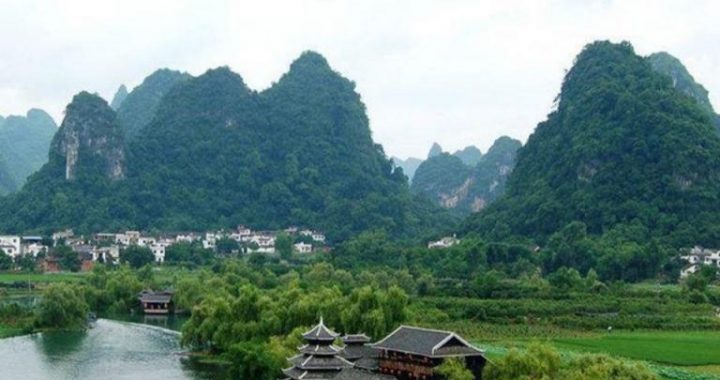

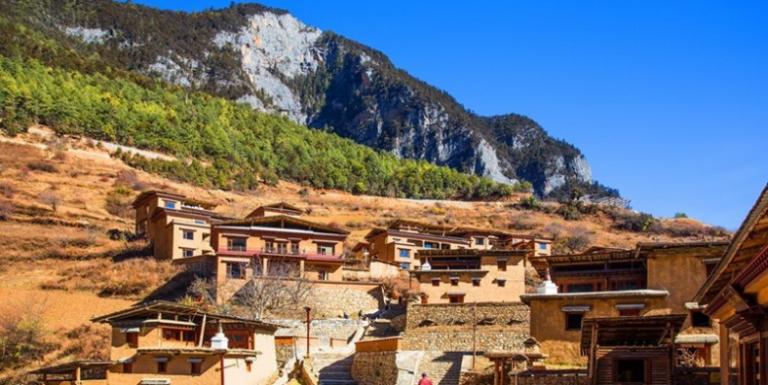

In Rock’s day, both of these villages were inhabited by the Nu, but over 80 years, Baihanluo shifted completely to a Tibetan population. Today, Chala remains inhabited by the Nu.Bai people are a populous group of lowland farmers restricted to western Yunnan. The Lanping valley is typical of Bai farming areas.Their fields yield two crops per year: rice or corn during the summer monsoon season and wheat, barley, or dried beans during the clear, dry winters. In the photos presented here, the fields are between crops, although at opposite ends of this double-cropping cycle: spring 1923 and fall 2004.As with the farming practices of other ethnic groups, the repeat photographs show that the pattern of terraced crop fields in the foreground remained stable during the intervening 81years. In contrast, the small, sloped fields along the base of the low ridge running through the center of the photographs have been abandoned. These abandoned fields have reverted to native shrublands and Yunnan pine forest.All lie along the main caravan route between the tea fields of southern Yunnan and the Tibetan Plateau, known as the Yunnan Tea and Horse Road. Most of these photographs are from Joseph Rock’s 1923 National Geographic Society expedition, but many other early travelers followed this route. They oftencommented in their writings about the stark landscape of this segment ofthe Lancang valley. Contrasting sharply with surrounding forests, the arid shrublands result from a “rain shadow”effect whereby high peaks to the west capture most of the rainfall and prevent it from reaching the canyon bottom.The first photo in this series is of Jongnongding, where the Yunnan Tea and Horse Road is visible traversing the slope in the center of Rock’s photo.Dominating the 1923 photo are the ruins of watchtowers built by Tibetans to ward off invading Naxi troops 500 years ago.The overall impression you get from the early photo is of a village that had just been carved out of the scrubby hillside. Indeed, according to a village elder, Jongnongding is a relatively new village, settled only about 100years ago. Several earlier attempts failed because of an irregular water supply.By 2001, the towers have disappeared under crop fields and the village in the foreground has a settled feel to it, with mature walnut trees and large houses.Dominating the ridge above Jongnongding today are roads, power lines, mobile phone towers, and the barely visible buildings of Yunling Township government, which moved to this site in 1984.Some scenic vistas have universal appeal. Think of the millions of photographs taken of El Capitan from the Tunnel View overlook in YosemiteNational Park, California. So it was along the Tea and Horse Road 100 years ago. After traveling a short distance upriver from Jongnongding, at least four western explorers stopped in almost the same place to photograph Guonian village,a striking oasis nestled in the arid Lancang canyon. Guonian posesses the two critical traits necessary to prosper in such a harsh region: relatively flat ground for terraced crop fields and a nearby mountain stream that provides irrigation water.Overall, little has changed since Emile Roux took the first photograph115 years ago. The Tea and Horse Road, seen traversing the slope in the right-center of all images, is still used as the main access to Guonian. Oneupgrade in transportation infrastructure is a new footbridge that provides easier access to villages acros the Lancang River than the bamboo rope crossing that it probably replaced. Within the village, walnut trees havegrown up and become more numerous. With great effort, villagers were able to divert water onto the slope in the center-left and converted a steep, dry land crop field to a terraced, irrigated one.As a companion to the previous set of Guonian photographs, this close-up illustrates the flat-roofed,”watchtower”style of architecture typical of houses in arid portions of southeastern Tibet. Then, as now, Tibetan houses consist of three stories:a livestock barn on the ground floor, human living quarters on the second floor, and crop drying and storage rooms on the top floor and roof. The most striking change seen here is in the large size of the modern houses compared to those in 1923. This trend is consistent among many repeat photographs of the area. Another very recent architectural trend, seen in the modern photograph, is for wealthy households to add a peaked, tile roof. This style is of Han Chinese origin and is considered a status symbol by local Tibetans. As was seen previously from afar, the walnut trees have grown much larger, now screening the foreground of the modern scene.Like many travelers along this caravan route, Joseph Rock’s expedition spent the night in Guonian,a village of about 10 houses in 1923 and almost twice that many now. Tibetans are very hospitable by nature. Major John Magruder, military attache with the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, passed throughthis valley in 1921 and made an observation that still holds true today:”It is the custom to find sbelter in the frst bouse available, and one enters with the same freedom as if the bouse were a public place. The bouses by day are open to friend and stranger, who roam at will about the place. Milk and buter tea are aluways auailable to the paserby”As Joseph Rock approached Guonian, he photographed the Lancang River as it winds out of the impressive canyon known as Moon Gorge. Aside from the stunning landscape, modern interest in this scene lies in the obvious expansion of irrigated agriculture. Level terraces on both sides of the riverhave been converted to crop fields during the intervening 80 years, irrigated with great effort by water from nearby streams.One stage stop north of Guonian along the Tea and Horse Road is Qizishui village, which lies a short distance from the Lancang up the Jushui River. Rock spent the night here and took this photograph in thelate afternoon, probably soon after arriving. He remarked that the Deqin Tibetans always dress lightly, even in the winter, because it is “always warm inthat dry trench.”In fact, Jushui is a phonetic transliteration of local Tibetan words that mean”warm place.”The two men pictured in the 1923 photograph may have been brothers from the household where Rock lived and likely were in a polyandrous marriage. Either one could be the biological father of the child, although in practice both would be called father. Polyandry is still common among Tibetans of the Lancang Valley, including Qizishui village. The 2002photograph was taken at a house where two brothers are married to the same woman, although the young men pictured are neighbors. Children resulting from the marriage are legal heirs of the oldest brother.Joseph Rock took this photograph looking up the Adong River valley,a major tributary of the Lancang River. The fields of Adong village are spread out below. In his notes for this photograph, Rock points out that the housesare all built on rocky ridges for defensive and economic reasons: defensive because these positions make good lookouts for invading brigands and economic because flat land for cultivation is scarce. While the first motive can be ignored in modern China, the second is still valid. Flat ground is scarce here. As can be seen in the 2005 photograph, however, more(and larger) houses now compose Adong, with many new ones located on prime agricultural land.The Tea and Horse Road splits in Adong. The down-valley route(to the left) takes a westerly course, eventually leading to Lhasa. The route up the Adong River(pictured here) leads over a high pass to Batang, an old Tibetan trading center on the Tibet-Sichuan border. Adong was a center ofTibetan resistance in the late 1950s. Just out of view around the corner, the trail enters a narrow gorge where, in 1959, the army of the powerful Adong landlord clashed with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. The story of this battle is now part of the oral history of the village.