Sacred and Religious Sites

7 min readEach ethnic group in northwest Yunnan had its own spiritual beliefLsystem, often involving some form of deity worship represented by animals, plants, or special places in the natural world around them. Likeeverything else about the culture and environment of northwest Yunnan, these indigenous religions have been in a constant state of flux over the centuries. For example, Khawa Karpo, now one of the most revered deities in Tibetan Buddhism, was originally a god(and sacred mountain) to the pre-Buddhist Bon religion of ancient Tibet. Some of these spiritual changes live on in the written and oral histories of Yunnan’s ethnic peoples. But two major waves of upheaval took place in the past 150 years that have placed many traditional religious practices and beliefs in jeopardy or resulted in their loss.The first was the large influx of foreign Christian missionaries in the mid-1800s, and the second was the establishment of the new China a century later.

Christians first entered China more than 1,000 years ago, but events in the mid-19th century resulted in the influx of thousands of missionaries. Great Britain’s victory in the First Opium War and the many”unequal treaties”imposed by foreign powers that followed, reduced China to semicolonial status for a century. Under the protection of the Western powers, Christian misionaries went on to play a major role in the Westernization of China in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.This enormous colonial wave crashed by 1953, by which time all foreign missionaries had left China following the communist triumph in the civil war.Formerly relegated to a few coastal cities, the unequal treaties specifically forced the Qing to admit Western missionaries to the interior of the country, including Yunnan. Christian missionaries provided the first modern medical services in the province. They opened the first schools for the lower classes and campaigned against the horrendous practice of foot binding in women.But the ultimate measure of success was the number of locals converted to Christianity. In this endeavor they appeared to have mixed results. Non-missionary Westerners traveling through Yunnan nearly always wrote admiringly of missionaries’ perseverance in very difcult, sometimes hostile conditions.

They also commented on how little impact they appeared to have in converting the locals of northwest Yunnan. But it appears that there were differences in the degree to which an ethnic group was open to conversion.Despite toiling for decades in Lijiang, several mission groups could notconvert a single Naxi. The Lisu of the Nu River valley were on the other end of the conversion spectrum. Protestant missionaries were successful in converting substantial numbers and that legacy lives on in the valley today. In between were the Tibetans; converts appeared to be localized around villages with churches and missions.One of the more fascinating of the missionary stories was that of the Catholics from the Societe des Missions Etrangeres du Paris (Paris Foreign Missions Society), established in 1658 and still in existence. In the early1840s, the Mision received an assignment from Pope Gregory XVI to enter Tibet and introduce Christianity, which ended up being one of their most difficult and dangerous tasks. Ten priests were murdered over this time. Ten more died there naturally, leaving France as young men, proselytizing on the Tibetan frontier for decades, and never returning home. In 1929, the Paris Foreign Misions leader realized they were not making headway among theTibetans, so he went before Pope Pius XI, who thought the monks of Grand Saint Bernard could help.

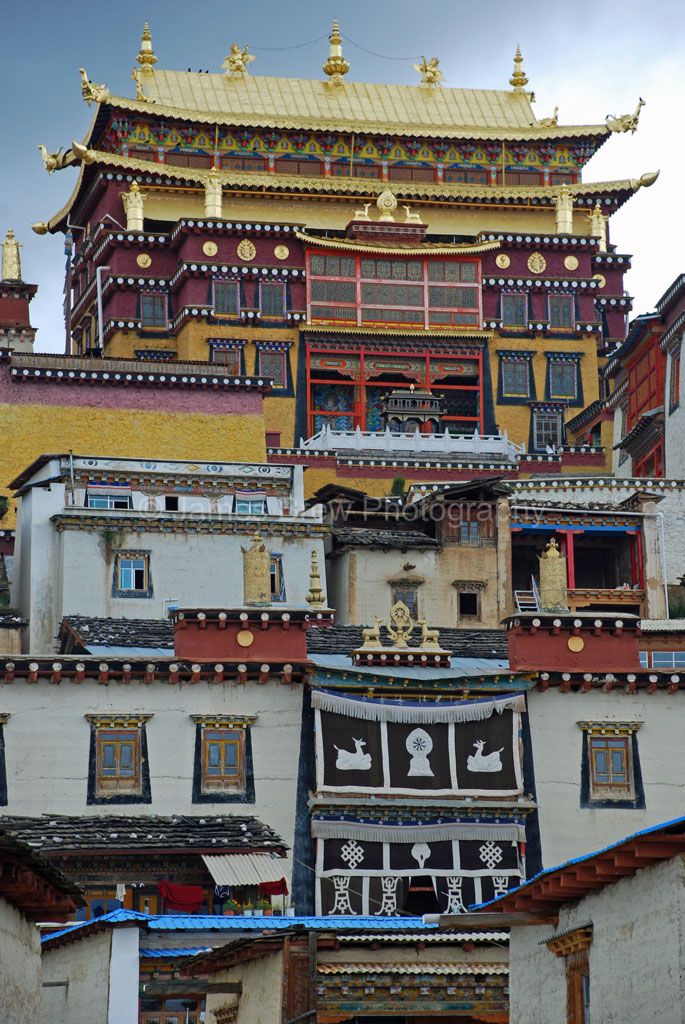

Famous for their Alpine hospice high on the Swiss-Italian border, the Pope thought these mountain-savy priests would be up for the task, and they supplemented French priests starting in 1930. Some of them were also murdered before all were expelled completely from China in the early 1950s.The second big upheaval started with the communist triumph in the Chinese civil war in 1949 and establishment of a new government that was officially atheist and discouraged any religious practice. The Chinese people later became violently anti-religious during the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Then policies changed in the early 1980s allowing for more religious freedom. Tibetan Buddhism survives today across a large swath of China, but other religions didn’t fair so well. The Naxi Dongba and Yi Bimo practices just barely survived in a few ancient practitioners, although both are experiencing a modest revival today. Others, especially the less-formalized animist beliefs of some mountain peoples, faded and have probably been lost to tides of Christianity and atheism.It is difficult to capture the intangible elements of spirituality on film, but many Western explorers were able to photograph the structural manifestations of these belief systems, such as stupas, temples, churches, and monasteries. I did document changes in one intangible spiritual element, the mountain worship of Tibetan Buddhists. Many important Tibetan deities reside in mountains.As mentioned earlier, one of the most sacred is Khawa Karpo. Throngs of pilgrims from across the Tibetan world circumambulate the mountain each year to gain karma for a reincarnated position in their next life that is better than their current one. In photographs, the worship of mountain gods is captured indirectly through images of the pilgrimage route.

But two major waves of upheaval took place in the past 150 years that have placed many traditional religious practices and beliefs in jeopardy or resulted in their loss.The first was the large influx of foreign Christian missionaries in the mid-1800s, and the second was the establishment of the new China a century later. Christians first entered China more than 1,000 years ago, but events in the mid-19th century resulted in the influx of thousands of missionaries. Great Britain’s victory in the First Opium War and the many”unequal treaties”imposed by foreign powers that followed, reduced China to semicolonial status for a century. Under the protection of the Western powers, Christian misionaries went on to play a major role in the Westernization of China in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.This enormous colonial wave crashed by 1953, by which time all foreign missionaries had left China following the communist triumph in the civil war.Formerly relegated to a few coastal cities, the unequal treaties specifically forced the Qing to admit Western missionaries to the interior of the country, including Yunnan. Christian missionaries provided the first modern medical services in the province. They opened the first schools for the lower classes and campaigned against the horrendous practice of foot binding in women.But the ultimate measure of success was the number of locals converted to Christianity. In this endeavor they appeared to have mixed results. Non-missionary Westerners traveling through Yunnan nearly always wrote admiringly of missionaries’ perseverance in very difcult, sometimes hostile conditions. They also commented on how little impact they appeared to have in converting the locals of northwest Yunnan. But it appears that there were differences in the degree to which an ethnic group was open to conversion.Despite toiling for decades in Lijiang, several mission groups could notconvert a single Naxi. The Lisu of the Nu River valley were on the other end of the conversion spectrum. Protestant missionaries were successful in converting substantial numbers and that legacy lives on in the valley today.

In between were the Tibetans; converts appeared to be localized around villages with churches and missions.One of the more fascinating of the missionary stories was that of the Catholics from the Societe des Missions Etrangeres du Paris (Paris Foreign Missions Society), established in 1658 and still in existence. In the early1840s, the Mision received an assignment from Pope Gregory XVI to enter Tibet and introduce Christianity, which ended up being one of their most difficult and dangerous tasks. Ten priests were murdered over this time. Ten more died there naturally, leaving France as young men, proselytizing on the Tibetan frontier for decades, and never returning home. In 1929, the Paris Foreign Misions leader realized they were not making headway among theTibetans, so he went before Pope Pius XI, who thought the monks of Grand Saint Bernard could help. Famous for their Alpine hospice high on the Swiss-Italian border, the Pope thought these mountain-savy priests would be up for the task, and they supplemented French priests starting in 1930. Some of them were also murdered before all were expelled completely from China in the early 1950s.The second big upheaval started with the communist triumph in the Chinese civil war in 1949 and establishment of a new government that was officially atheist and discouraged any religious practice.

The Chinese people later became violently anti-religious during the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Then policies changed in the early 1980s allowing for more religious freedom. Tibetan Buddhism survives today across a large swath of China, but other religions didn’t fair so well. The Naxi Dongba and Yi Bimo practices just barely survived in a few ancient practitioners, although both are experiencing a modest revival today. Others, especially the less-formalized animist beliefs of some mountain peoples, faded and have probably been lost to tides of Christianity and atheism.It is difficult to capture the intangible elements of spirituality on film, but many Western explorers were able to photograph the structural manifestations of these belief systems, such as stupas, temples, churches, and monasteries.I did document changes in one intangible spiritual element, the mountain worship of Tibetan Buddhists. Many important Tibetan deities reside in mountains.As mentioned earlier, one of the most sacred is Khawa Karpo. Throngs of pilgrims from across the Tibetan world circumambulate the mountain each year to gain karma for a reincarnated position in their next life that is better than their current one. In photographs, the worship of mountain gods is captured indirectly through images of the pilgrimage route.