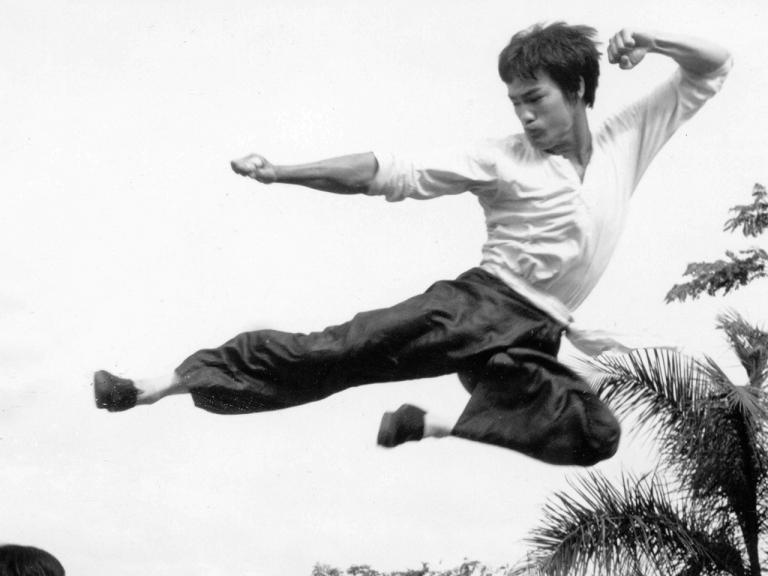

Bruce Lee’s Shaolin Way

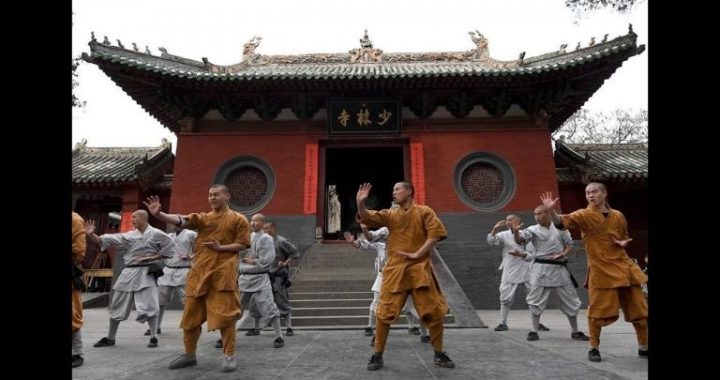

8 min readIn order to understand the full impact and achievement of Bruce Lee’s later life and work, it’s important to understand the roots from which it grew. Martial art was introduced to sixth-century China by an Indian monk, Bodhidharma – known in China as Da Mo – a member of the warrior caste who had entered the priesthood and then sought to spread the teachings of the Buddha. While crossing the mountains of northern China on foot, he came across the monastery at Shaolin. While there Bodhidharma saw how unhealthy and lethargic the scholarly monks had become. They didn’t take kindly to being told this and refused to allow the wandering priest to stay there, so Bodhidharma retired to a nearby cave to meditate.

Legend has it that he stayed there for nine years, other accounts say that it was only forty days, but the generally accepted period is three months. During his time in the cave Bodhidharma helped many of the local people and news of this reached Shaolin. As a result, when he returned to the monastery he was allowed in. Bodhidharma explained to the monks that as the body, mind and spirit function as one, any imbalance in this interdependent system will lead to illness, so he devised a series of exercises designed to extract chi (life force) from the air by moving consciously in coordination with the breathing, in a prototype of what we might now recognize as chi kung. These exercises also had the effect of reconnecting the monks with the natural world and soon they developed a series of exercises derived from watching the movement of animals, which became the basis of Shaolin kung fu.

These ‘animal forms’ were not only the basis of the method the Shaolinmonks used to stimulate and rebalance the body-mind system, they also became a fighting method which they used to protect themselves from bandits while on their travels to market or other monasteries. The Shaolin way of life flourished for over a thousand years until, in the eighteenth century, the Manchus seized power in China, even though they represented only a small minority of the population. Positions of authority were only open to ‘Manchurian candidates’, and to keep the Han majority under control, the Manchus imposed severe restrictions on them. The Han males were required to shave their foreheads and wear their hair in a pigtail so as to make them more easily identifiable, while the women had to bind their feet to restrict their movements. There were even limits on the number of knives a Han household could own.

Surprisingly the Manchus allowed the continuation of Han monastic life, and as a result the Shaolin monastery became a natural home for dissidents and a hotbed of rebellious plotting. Because it took eighteen years to train a fully fledged Shaolin martial artist, it was not a realistic method of training revolutionaries to take on the Manchu soldiers. To overcome this the five most knowledgeable elders of the Shaolin temple, who have entered legend as ‘the Venerable Five’, devised a fighting style to overcome all the other known styles and which was faster to learn. The elders, each a master of his own discipline, pooled their knowledge in order to create, or perhaps reveal, a set of root fighting principles. The first thing they did was to note the two essential aspects of any martial art: its yin or yang qualities. Firstly there were hard external (yang) styles that tended to commit the body’s placement before a kick or punch could be landed. This generated a lot of power but left the practitioner inflexible. Secondly there were the soft internal (yin) styles, where the body’s weight and commitment are more adaptable, elusive and spontaneous, but which tend to lack power. The elders reasoned that to get the best of both worlds they needed to develop techniques that could be landed quickly and unpredictably, yet with power.

This new fighting method involved strikes thrown with total commitment, but which could be halted abruptly and instantly re-thrown from another angle. They also determined that this new method would best suit close-range fighting. Long-range kicks and swinging punches from an opponent would be frustrated through a system of jams, straight-line deflecting strikes, simultaneous blocks and strikes and mobile and adaptable footwork patterns. Once in close-fighting range the second aspect of this new method wouldreveal itself where physical contact with the opponent’s limbs would trigger the right moves spontaneously. The Shaolin elders renamed the hall in which this fighting method was evolved as the Wing Chun hall: wing chun translating variously as ‘hope for the future’ or ‘eternal springtime’. This expressed their hope for the evolution of the Shaolin martial arts as well as their hope of defeating the Manchu rulers. But in 1768, before this new method could be put into practice, the Manchus raided the Shaolin temple and destroyed it. The only one of the five elders to survive was a nun, Ng Mui. While in hiding Ng Mui continued to refine and develop this new fighting method, calling it wing chun in remembrance of its original intention. Soon after coming out of hiding, Ng Mui met Yim the daughter of a bean- curd seller in a local market. The nun learned that the girl was having trouble from a local gangster who demanded that she marry him.

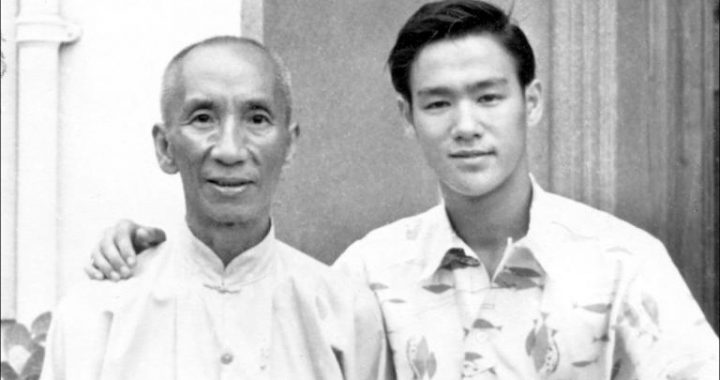

The gangster had threatened to ruin Yim’s father if she didn’t comply. The nun listened to the story and then advised a course of action. Knowing that she had perfected a fighting method that was both ruthlessly efficient and rapidly taught, she advised the girl to tell the gangster she would marry him, but only if he could defeat her in a fight. In those days it took several months to arrange a marriage, giving them time to implement Ng Mui’s plan, and as Yim was a small, delicate girl, the gangster readily took up the challenge. At the appointed time, when the fight took place, the burly gangster attacked the young girl with a wild roundhouse punch which she blocked as she made a simultaneous counter strike, knocking the bully unconscious with her first blow. Yim’s father asked Ng Mui if she would take care of his daughter and so the girl followed her new guardian to a nunnery. There Ng Mui renamed the girl Wing Chun, knowing that she was to be the future of the art. Yim Wing Chun stayed with Ng Mui until the nun died, then later married a salt merchant and taught him the art. After a further six links in the chain the art passed to Yip Man, who taught William Cheung who introduced Bruce Lee to it. Yip Man began to learn the art of wing chun at the age of thirteen, but didn’t begin teaching it until he was nearly sixty. At the age of thirteen, the young Bruce Lee began training under him. Although he was a mild-mannered and slightly built man standing only five-and-a-half feet tall, Yip Man was aformer policeman and cut an imposing figure.

He also held definite opinions. He shunned Western clothing, would not pose for publicity photographs and felt strongly that only the Chinese should be taught wing chun. Bruce Lee was attracted to the style because of its economy and directness and its emphasis on developing energy. As he said, it gave the ‘maximum of anguish with the minimum of movement’. Where Shaolin kung fu had thirty-eight forms (practice routines) wing chun has only three: the sil lum tao (Cantonese for ‘Shaolin way’), chum kil (‘searching for the opening’) and the deadly bil jee (‘stabbing fingers’). Wing chun is based on the principle that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. For example, it has none of the big circular movements of tai chi. Although there are kicks in wing chun, none is landed higher than the opponent’s waist; the emphasis is on gaining position for close-in fighting. All attacks are directed straight at the central axis of the opponent’s body, just as it is one’s own axis which is defended. Crucial to the effectiveness of wing chun is the unique training practice of chi sao or ‘sticking hands’. The initial objective is to not lose touch with your opponent – you don’t push so hard that you move him, but you don’t hold back so much that you lose contact, hence ‘sticking’. Chi sao is not so much an actual fighting technique as a practice designed to help one develop sensitivity to the shifting balance of physical forces in a fight. This is based on the fact that when two people make a physical connection, an actual point of contact exists.

With sufficient practice, it is at this point that any move, or even intended move, can be felt instinctively, a response which is called the contact reflex. This is similar to the experience of a fisherman who doesn’t have to see the fish nibbling the bait at the end of his line to know he has a bite. While developing this reflex action to the point where it has become not just second nature but first nature, the student passes through various levels of chi sao training. At each stage the student must progress from predetermined moves to random moves until, at the advanced stage, he or she can practise while blindfolded. It’s important to understand that while the practice routines of chi sao do not apply to combat situations, the awareness and coordination they develop are essential. Chi sao gave Bruce Lee his first practical experience of the interplay of the energies yin and yang, the active and yielding forces. Wing chun has one further unique training method in which a woodendummy representing the opponent is used to simulate almost all conceivable combat situations in 108 practice moves. The wooden dummy also has the effect of toughening and conditioning the hands, the student is able to lock out when striking it, using the kind of power that might injure a sparring partner or cause injury to his or her own joints when working alone.

Every day after school, Bruce Lee headed straight to Yip Man’s class, anticipating training by practising his kicks on the trees that he passed on the way. Even after training, Bruce would still thump the chair next to him as he sat at the dinner table at home. Before long William Cheung began to hear complaints from some of the older students who were coming off worse in their training encounters with Bruce. He recalls: They were upset because he was progressing so fast. I noticed that even when he was talking he was always doing some kind of arm or leg movement. That’s when I realized that he was serious about kung fu.