Game of Death 22 Enter the Dragon of Bruce Lee

17 min readIn 1967, when Bruce was given the opportunity to meet the basketball giant Big Lew Alcindor, he jumped at it. He had to – Big Lew was over seven feet tall, and Bruce was intrigued as to how he might fight a man of that height. Big Lew became one of Bruce’s celebrity pupils, and when he later converted to Islam he took the name Kareem Abdul Jabbar. As the ace centre for the Milwaukee Bucks, and later the Los Angeles Lakers, he became one of the top players in the game.

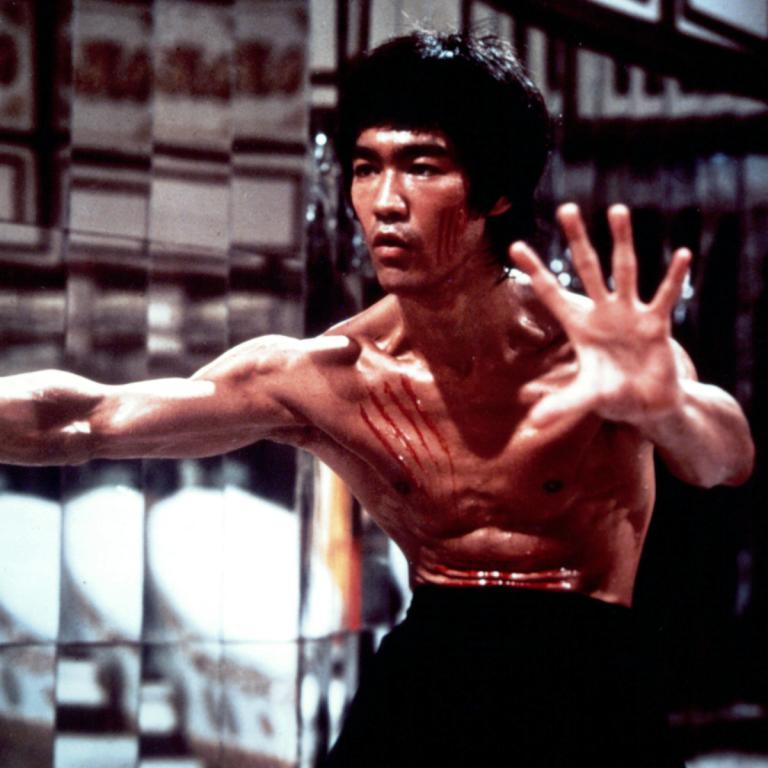

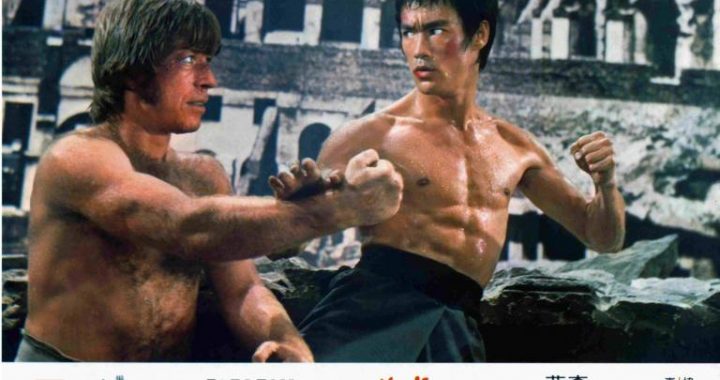

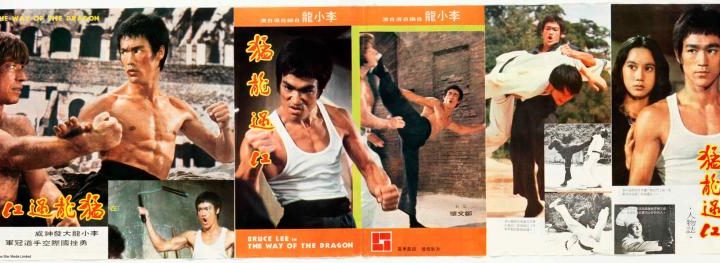

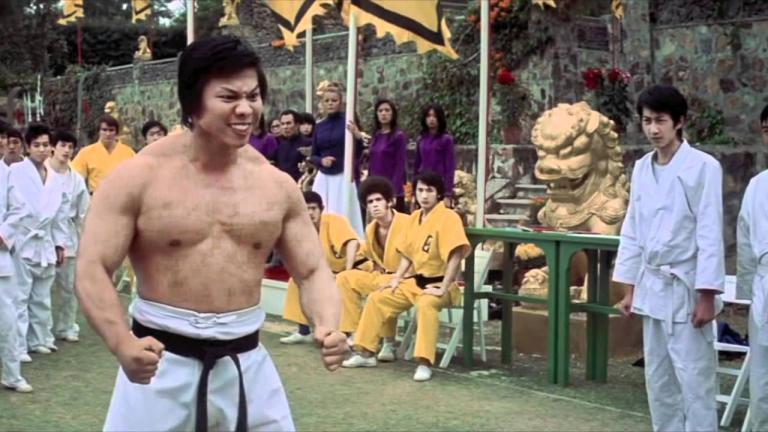

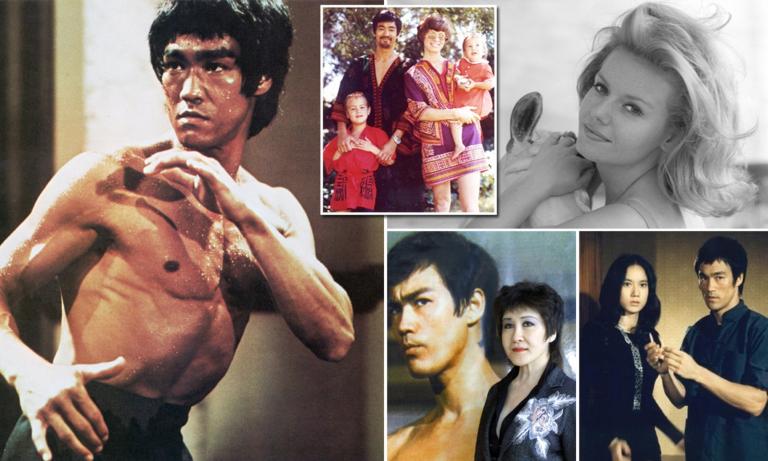

With Way of the Dragon completed, an exhausted Bruce planned to take a short rest, but in the spring of 1972 – after Fist of Fury was released – when Bruce heard that Jabbar was in Hong Kong, he swiftly arranged some action scenes to be filmed for Game of Death. There was no script for Game of Death as yet, but Bruce had enough of an idea of the story to be able to take advantage of Jabbar’s visit, and the two of them spent a week sparring and acting out fight scenes in front of the cameras. To make sure the action was convincing, Bruce rehearsed one particular kick nearly 300 times. The result is some intriguing and strangely elegant footage of Bruce fighting a man who towers above him. In Bruce’s mind the opening shot of the film was also clear; his notes read: As the film opens we see a wide expanse of snow. Then the camera closes in on a clump of trees while the sounds of a strong gale fill the screen. There is a huge tree in the centre of the screen, covered in thick snow. Suddenly there is a loud snap and the branch of the tree falls to the ground. It cannot yield to the force of the snow, so it breaks. Then the camera moves to a willow tree, which is bending with the wind. Because it adapts to the environment, it survives. What I want to say is that a man has to be flexible and adaptable, otherwise he will be destroyed. The rest of the story had been evolving in Bruce’s imagination ever sincehe’d stood on the northern border of India and looked out on the pagodas of Nepal. A national treasure is stolen and placed on the top floor of a pagoda on an island off the coast of Korea. As the hero, Bruce Lee has to recover the treasure. Outside, the pagoda is defended by a band of fighters, led by a hulk of a man, while inside each floor is defended by a master of a particular martial art. The pagoda is a training school for martial artists of different traditions, where each floor is given over to students of different forms of combat. The climax of the film occurs on the uppermost floor where Lee, the master of ‘anything that works’, fights Jabbar, the master of ‘no style’, a giant who fights unpredictably. Here all the rule books are thrown out as each man relies entirely on his wits and natural native fighting skills. This, the final scene, entitled ‘The Temple of the Unknown’, was now in the can. Bruce Lee was determined that expertise and quality would be the hallmark of this film. He intended to assemble the most talented array of fighters available and had already called on Dan Inosanto to be the guardian of one of the floors. Dan practised escrima, together with its variants kali and arnis, the ancient Filipino art of stick fighting.

The art was named by the Spanish conquerors – escrima is Spanish for ‘skirmish’ – who soon realized its effectiveness and banned it. In the northern Philippines, the movements were kept alive by practitioners who disguised it as a dance, while in the south, where the native Muslims expelled the Europeans, the art continued to flourish. Bruce forwarded a China Airlines ticket to Inosanto, who flew out as soon as he could make a break in his schedule. Linda met him at Kai Tak airport because Bruce couldn’t have gone there without being mobbed. Within a couple of days they were working out their moves, using a video machine to check the action after each take, a technique Bruce pioneered in his Green Hornet days. Over several days, they worked out the basis of their episode, which was entitled ‘The Temple of the Tiger’. Three weapons are used during this confrontation. First, Inosanto uses the double sticks while Bruce uses a Chinese bako, a thin whip-like bamboo. As the two face off, Inosanto taps out a traditional challenge with his stick. Bruce’s mocking response is the ‘rat-tat-ta-tat-tat’ knock of the postman.

After Bruce disarms Inosanto, they pick up nunchakas for a duel to the death. Inosanto had originally introduced Bruce to the weapon; but the resulting footage of this scene shows that Bruce had mastered it better than his teacher. Inosanto recalls that shortly after he met Bruce in 1964, he showed him afew basic escrima techniques. At the time Bruce hadn’t been much impressed and Inosanto had thought no more of it. On this visit to Hong Kong, eight years later, when the subject came up, Bruce told Dan what he liked and didn’t like about what he’d seen of escrima. ‘I was flabbergasted when he grabbed the sticks and said, “OK, now I’ll show you what I would do,” ’ says Inosanto. ‘I watched him closely, and with no previous background or training he ad-libbed a style of escrima he could never have known existed. Shocked, I yelled out, “Hey, that’s larga mano!” Bruce said, “I don’t know what you call it, but this is my method.” ’ Inosanto adds that Game of Death was intended to illustrate the same point: ‘Bruce wanted to show imagination rising above tradition.’ So while Inosanto was dressed in the traditional Muslim costume and headband, Bruce wore a modern yellow and black catsuit. Bruce had revelled in the free hand he had in making Way of the Dragon. Now, in Game of Death, he continued to improvise as he went along, taking advantage of the fact that the sound would be dubbed on later. Like a silent film director of old, he even shouted directions to his actors as the cameras were rolling. Bruce forgot all about resting as he enthusiastically planned further duels. A third combat scene was filmed with Chi Hon Joi, a seventh-degree black belt in the Korean art of hapkido, which relies on high kicks. While filming their scene, the Korean had a rigorous enough time of it to comment that he didn’t want to act in any more movies with Bruce Lee. Bruce’s pointed response was that he was considering re-shooting the scene, this time with a female martial artist called Angela Mao.

Bruce’s disparaging comment to Chi Hon Joi related to an earlier incident. When Bruce had been finishing scenes for Way of the Dragon in Hong Kong, another film Hapkido, aka Lady Kung Fu, was being made there with some up-and-coming martial artists called Carter Wong, Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung. The female lead in the film was Angela Mao, who was being taught hapkido by the film’s star, Wong In Sik, who said he wanted to ‘give her an edge’ over Chinese martial arts actresses. Wong In Sik had apparently been hitting his Chinese stuntmen without any holding back, saying he wanted to show that the Korean art was by far the most powerful and effective. Word of this had got to Bruce, who arranged to bring in the Korean for Way of the Dragon. Bruce then gave him a robust demonstration of the Chinese arts that left him in no doubt of the error of his ways. In doing the same to Chi HonJoi, Bruce had been making doubly sure his point had not been missed. For Game of Death, at a later stage Bruce was planning to include Betty Ting Pei and the Australian actor George Lazenby, but neither they nor Bruce had any idea what their roles would be. Lazenby, like Bruce Lee, had shot to fame overnight – in Lazenby’s case, from doing chocolate bar commercials to replacing Sean Connery as James Bond in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service – but Lazenby hadn’t been a great success as Bond and his career was in the doldrums. Fortunately the film had only just opened in Hong Kong and Lazenby had chosen exactly the right time to go knocking on Raymond Chow’s door. Taky Kimura, who was also asked to play a role in Game of Death but declined, says, ‘He sent me a plane ticket to go to Hong Kong but I said, “I’ve got three left feet and you know it. You don’t need me. Do me a favour, I’m not looking for fame and fortune, I’m happy to see you doing well.” He said, “I’m the director and producer; everyone looks good in my films.” I said, “I guess I can’t refuse.” I recognized the feeling behind what he was doing. But in October the import business I had started was just about to go and I wasn’t able to go to Hong Kong. Then Linda called me and said don’t bother, something else was breaking and Game of Death was being put on the back burner.’ At the time, Taky Kimura was also going through a severe personal crisis which left him emotionally devastated and haunted by the idea of suicide: ‘I lost two brothers a month apart and then my wife left me,’ he explains. ‘Bruce said, “Taky, I haven’t met your wife, but I’ve counselled you before. You must do everything in your power to solve the thing but, at some point in time, you may just have to walk on.” I’d lost everything. When people tell you things like that, there’s not always a lot of pith in it, but coming from him . . .’ From wherever he happened to be in the world, Bruce would call to give support to his friend, saying, ‘Walk on, Taky. Just walk on.’ When Bruce’s old friend Doug Palmer arrived on a visit to Hong Kong with his wife, he managed to track Bruce down via Golden Harvest, who passed on a message. Palmer’s notes recall: Five minutes later the phone in our hotel room rang. ‘You son of a gun,’ Bruce yelled when I answered. ‘What are you doing in Hong Kong?’ He and Linda came and picked us up and took usback to the huge house he was having work done on in an exclusive part of town called Kowloon Tong. The lot had a high wall around it with broken glass and spikes set in the top. He had made it, but fame had a price. His kids had to be escorted to and from school so they would not be kidnapped. My wife, Noriko, had to use the toilet; Bruce produced a bunch of keys to unlock the bathroom – apparently he had to keep every room in the house locked to guard against theft by the workmen. While we were at his house, Bruce was looking through his mail and he read a letter from his old friend, James Lee, in Oakland. I could see Bruce frowning as he read, then I heard him whisper to Linda to send James five hundred dollars. Bruce told me later that James was dying of cancer.

Later we went out to dinner. When we stopped at a light, people on the street or in adjacent cars would gawk in at him. The restaurant was full and we had no reservation, but they soon produced a table. I’m not sure if anyone else in the place got their dinner because every waiter was hovering near our table. The next day we visited the movie studio where Bruce was filming Game of Death. He had recently brought Kareem Abdul Jabbar over to Hong Kong to shoot a fight scene, which had a very powerful David and Goliath quality about it. Bruce was very happy about the way the scene had turned out, in contrast to a more recent one where he had flown in a martial artist from Korea and was very disappointed with the calibre of the man’s performance. Bruce also had a few stories to tell about Kareem Abdul Jabbar. When he arrived in Hong Kong, Kareem let it be known that he was very interested in having ‘a date’. Bruce tried to arrange something for him. When the girl showed up and was introduced to Kareem, she flat refused. No one had told her how big Kareem was. Kareem became very angry. ‘He’s very sensitive about his height, you know,’ said Bruce, chuckling. In May 1972, Bruce Lee’s boyhood friend Unicorn met with Tang Di, a representative of the Sing Hoi Film Company, at the Peninsular Hotel. With the sudden popularity of martial arts films, the company decided it wanted to get in on the act. As Tang discreetly put it to Unicorn, ‘Frankly speaking, your name, of course, won’t sell; but if you have “another” who can help you, the film will not only sell, it will earn a lot of money.’ In short, Bruce Lee’s involvement in the picture was the condition that would secure the starring role for Unicorn. Bruce gave Unicorn the role of the head waiter in Way of the Dragon, but when Unicorn had presented the idea to Bruce, suggesting that he might do the fight choreography, he didn’t expect him to go for it. After all, the budget for the film was so low it was close to the earth’s core. Bruce replied that, although he realized he was being manipulated, he would do what he could to help, but when Bruce attended a publicity bash for the film at the Miramar Hotel in Kowloon, he got all the attention and had to ask the press photographers not to ignore Unicorn.

As filming started in August 1972, it soon became obvious that Unicorn was out of his depth as a leading actor and again Bruce had to step in. Aswell as supervising the action, Bruce came up with several script ideas, spending a day at the set while the cameras rolled. When the film – imaginatively titled Fist of Unicorn – was released soon afterwards, Bruce Lee was not only credited as the martial arts advisor but was given star billing. Footage of Bruce arriving on the set and of him rehearsing the actors had been contrived to fit a new storyline. Bruce could only issue a legal letter condemning the sorry project, and although Bruce’s friendship with Unicorn continued, the incident increased his wariness of others. As for Unicorn, one reviewer wrote, ‘One only has to witness his stolid approach to every scene, his constipated countenance, resplendent as it is with a neck that is evidently part of his chin, and eyebrows modelled on Roger Moore at their tugging fishhook best.’ Bruce Lee’s superstar status made him vulnerable to all kinds of exploitation. His name was used to endorse products he’d never heard of, much less used, while quotes attributed to him were used to hype films he’d never seen. Producers advertised offers to him in the pages of the Hong Kong press, while seeking only to generate publicity for themselves and increase their prestige by some kind of association, however tenuous. The situation in which he now found himself had changed so quickly that a normal life was no longer possible. As the press became ever more ridiculous in its excesses, Bruce used to wake up to find parts of a previous evening’s conversation in a restaurant splashed across the newspapers, and headlines like BRUCE LEE LINKED TO MASS MURDER because his friend Kareem Abdul Jabbar had rented a house in the US whose occupants had recently been killed. In the 1960s, audiences had tired of Shaw’s musical epics and begun flocking to see samurai movies. Without missing a beat, Run Run Shaw switched production from the sentimental to the bloody, but soon samurai movies came to a messy end, quickened by a series of speeches made by Chinese leader Chou En Lai attacking Japanese imperialism. With no gunfighting or sword-fighting tradition to base his films on, Shaw set out to revive kung fu films, starting with The Chinese Boxer, a film whose appeal was a combination of national feeling, secret societies and action. This was quickly followed by King Boxer, The Killer and The New One-Armed Swordsman, starring Wang Yu, who became kung fu’s top star by beating Shaw’s contract system and hiring himself out on a film-by-film basis whereby he was able tocommand a fee of $20,000 per film. These movies broke out of the Oriental market to find success around the world, and the Hong Kong press started calling Shaw ‘Mr Kung Fu’.

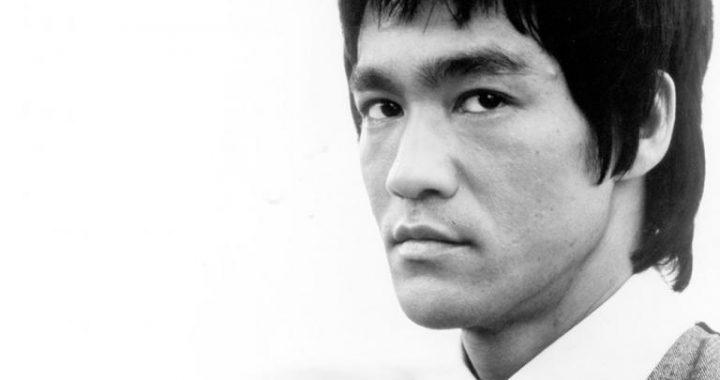

But audiences were quick to realize that there was a new kid on the block who was the genre’s natural star. Ironically, Shaw had opened the door for his most bitter rival to better him. When Newsweek wrote about the emerging phenomenon, the story was headlined: BRUCE LEE: THE BRIGHT STAR RISING IN THE EAST. The LA Times columnist Robert Elegant also wrote an article heralding Bruce, and Raymond Chow lost no time in setting up US distribution. In his office at Golden Harvest, Bruce Lee was besieged with offers that continued to arrive daily. The only reminder of his past struggles was a pair of broken spectacles, which he kept to remind him of the time he couldn’t afford to have them fixed. They were the same spectacles he’d worn when he’d disguised himself as a telephone repairman in Fist of Fury. Now he was in an almost unprecedented position for any movie actor, let alone a Chinese one. He was potentially the highest-paid actor in the world, and could work in Europe, the US or the Orient, plus he was a partner in his own production company. Some years after Bruce Lee first came to Fred Weintraub’s attention, the Warners executive was still trying to secure him a starring role. Weintraub says, ‘When I kept failing to get a feature going for Bruce, I told him to go to Hong Kong and make a film I could show people. He eventually sent me a print of The Big Boss and I went to Richard Ma [Warners head of Asian distribution] with it because he was the only one who understood the genre. I also arranged a private showing for Ted Ashley and he said, “Try and get something going.” ’ When Bruce completed Fist of Fury, Weintraub was again sent a print. Now, along with box-office figures from the Mandarin circuit, Warners realized that Fred Weintraub might be on to something, though he adds, ‘There still wasn’t a lot of enthusiasm for it. Nobody believed it would ever get done.’ At the time of Nixon’s high-profile visit to China, awareness of Asian culture was stirring in America, and Richard Ma thought it might be just the time to expose kung fu films to a wider audience. Rather than give money to Run Run Shaw by taking his films, Ma suggested an original project, saying he knew a guy by the name of Bruce Lee. Ma had a hard time trying toconvince his senior executives that this was a good idea, even though the budget for the proposed film was roughly equal to what they’d spend on a TV pilot episode. Fortunately, Warners president Ted Ashley was convinced, so Fred Weintraub and Paul Heller were appointed co-producers and a subsidiary company, Sequoia, was set up to manage the project. Scriptwriter Michael Allin was hired to write a martial arts film to be called Blood and Steel and Weintraub set off for Hong Kong to do a deal whereby Sequoia and Concord, the production company Bruce set up with Raymond Chow, would co-produce the picture. This proved not to be the simple formality Weintraub had hoped for, and after two weeks in Hong Kong, he still didn’t have Chow’s signature on a contract. Although Weintraub found Bruce to be in favour of the project, he could never seem to get the two Concord partners together in the same room at the same time. Raymond Chow seemed to be dragging his heels, sensing that he was losing control.

Weintraub was about to call it a day, return home and ditch the project, but the evening before he was due to return to the US he decided to give it one last shot. That evening he managed to get Bruce and Raymond to go to a restaurant, and after dinner Weintraub told Bruce that Raymond Chow was right to protect him and that the attempt to go international wasn’t worth risking the successful career he had built up in Hong Kong. Weintraub said that it was all academic anyway as he couldn’t make a deal. Bruce looked over at Chow and said, ‘Make the deal,’ so Chow could only smile and add that he thought it was a wonderful idea. In October 1972, Bruce Lee and Raymond Chow flew to the US to finalize the details and meet with the actors and director with whom Bruce was to work. In his room at the Beverly Wilshire hotel Bruce had hardly unpacked his suitcase before he called Steve McQueen to tell him that he was to star in his own US-made film. Bruce wasn’t about to take a chance that McQueen might have missed the many interviews in which he’d reminded McQueen that he was just as famous now. Bruce Lee then called Stirling Silliphant. Part of a deal Silliphant had just done with 20th Century Fox included the script of The Silent Flute. The writer thought Bruce would be delighted, but Bruce hadn’t forgotten about India, and far from giving his blessing to the film being made, he told thewriter he was now worth a million dollars and that they couldn’t afford him any more, even though Coburn and Silliphant had done more than most to help Bruce when he’d been struggling. Bruce then suggested that if The Silent Flute were ever made, James Coburn would have to accept second billing. Using the very same words that had stung him so many years ago, he added, ‘And why should I carry him on my shoulders?’ All of Bruce Lee’s closest friends belonged to the period of his life when he was first and foremost a martial artist. Now, because of his success, he was experiencing a shift in his relationship with many of them, like Unicorn.

He realized that these old friendships were changing or fading away, but in enjoying his success, even at the cost of alienating the few people who had genuinely helped him, he was now driving some of them away. Perhaps Bruce’s behaviour was partly due to the blow he’d taken when he realized that one of his greatest friends, James Lee, was dying of black lung, an occupational disease of the welding trade. James had been given only weeks to live when Bruce invited him to Hong Kong for the premier of Way of the Dragon, hoping that James would at least see the city and that Bruce would see his old friend before he died. Sadly James wasn’t able to share in Bruce’s success as he was far too unwell to travel, and he died on 28 December 1972, leaving Bruce emotionally devastated. Two days later, as Bruce grieved, Way of the Dragon opened and, almost unnoticed, surpassed his prediction that it would make $HK5 million by earning $HK5.5 million in the first three weeks of its opening run. Bruce knew that a good deal of his success was due to his friend’s help and encouragement with his conditioning and training. At times, James Lee had been more like a father to him than his own father.