Impacts of Climate Change in Shangri-La

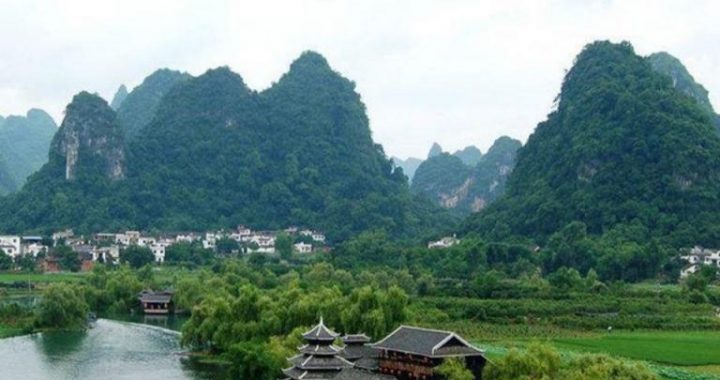

4 min readQome of the most dramatic and observable effects of rapid changes in the) Earth’s climate system occur at high latitudes in the Arctic and Antarctic.Shrinking sea ice and retreating glaciers get the most media coverage, but effects also extend to a broad range of social and ecological changes in villages, infrastructure, and wildlife. Since thermal thresholds dominate so many physical and ecological processes at high latitudes, these systems are changing faster than in the mid-latitudes where most of us live. It is the same in mountains, the high-elevation analogs to high latitudes. The largest mountain mass of them all is the Himalayan-Tibetan Plateau complex, which is often considered the Earth’s Third Pole. It appears to be changing just as quickly as the north and south polar regions, with effects that are visible and measurable, influencing both biological richness and people’s livelihoods.

When I went to work in Yunnan in 2000,I vaguely understood climate change to be a potential consideration for designing conservation projects.For a person from the mid-latitudes and mid-elevations of Idaho, climate change was still somewhat abstract to me. But while living in Deqin I saw first-hand the rapid retreat of the Mingyong Glacier in just two years and the consequent impacts on water supply in Mingyong village. Although this was the first indication that something bigger was happening, climate change quickly moved from abstraction to reality as I accumulated repeated images from across the region that documented impacts to human communities and ecological systems, as well as to glaciers.Repeat photography is a common way to illustrate and measure theretreat of glaciers due to climate warming. In fact, the first repeat photo study was conducted in the Tyrolean Alps in 1888 to document glacial change. However, documenting ecological effects with imagery is more difficult than noting change in glaciers. Luckily, in the high elevation systems of northwest Yunnan we have a great visual cue to work with: the upper elevational boundary between the forest zone and the non-forest alpine zone on mountainsides. Termed upper treeline, this natural boundary is chiefly thermally controlled as the low-temperature limit above which trees cannot survive.

It is easy to see and it is a great indicator of a warming climate. In many ways observing treelines over time is the same as documenting glacial change, but we are observing the advance of forests up a mountain instead of their retreat.Visual evidence from photos, of course, is only a manifestation of changes actually taking place in temperature or precipitation. Meteorological data are sparse from this part of the world, but there is a weather station in Deqinthat was established in 1955. It shows that temperatures rose steadily over the period of record, with an especially sharp rise after 1980. This pattern, an abrupt change in the rate of increase after 1980, is seen in climate records around the globe. The annual rate of temperature increase at Deqin is twice the rate observed for China as a whole. Stations at Lijiang and Zhongdianexhibit a similar pattern of temperature increase, but the annual rate of increase has not been as high as at Deqin.In some of the photo sequences that follow,I point out the implications of climate changes for humans. But we are only beginning to understand how human societies will be affected.

For the Himalayan-Tibetan Plateau region, water supply is a critical issue because its glacial-fed rivers support more than 1.5 billion people in 10 countries. Interestingly (and ominously), downstream communities are developing systems for water use and distribution for increasing water supplies as glaciers melt faster. Butwater supply will eventually decline in some basins as their glaciers meltcompletely. When a mountain glacier disappeared in Ecuador recently, civil strife resulted among communities and neighbors reliant on a water source that initially surged, but is now disappearing. The greatest effects in the short term, however, will be noted at high elevations, especially among Tibetans whose livelihoods are directly tied to these rapidly changing ecosystems for medicine, food, and spiritual sustenance. On the other hand, warmer conditions may provide new crop opportunities for cash and subsistence.Wine grapes are now successfully being grown farther up the Lancang River valley in Deqin County than previously. Deqin Tibetans may someday be able to diversify their agriculture to include rice as a summer crop, instead of just the corn they are restricted to now.Rapid climate change also presents disturbing challenges for the booming tourism industry in northwest Yunnan. Yulong Snow Mountain near Lijiang is the site of the largest glacier resort in China, visited by 1.7 million tourists in 2004. The small glacier they are attracted to is retreating at about 20meters per year. Surveys found that about 30 percent of the 3.5 million tourists that visited Lijiang in 2004 would not come if the Yulong glacier were absent. This is a potential direct economic loss to Lijiang of around 800million Chinese yuan(U.S.$134 million) annually. In 2001, Deqin County invested millions of yuan in infrastructure construction that provides tourists with a breathtaking glacier experience. It now appears that its utility may be shorter-lived than officials had hoped.As I’ ve stated elsewhere, most people of northwest Yunnan are poor and, as such, emit very little greenhouse gas pollution. More critically, their livelihoods are closely tied to the natural resources and productivity of the places where they live.

They have a limited ability to move, and their social systems are much less resilient to change than middle-class and urban populations that can draw on food, shelter, and energy resources from acrossthe globe. While there may be some benefits from warming, the rapidity of change at these high elevations does not bode well for such communities. So, here is the major climate lesson I have learned in my years of living, working, and photographing change in the mountains of Yunnan: the people who have contributed the least to the problem are likely to suffer the most.