Kunqu and the Spirit of Chinese Culture

8 min readKunqu opera is China’s oldest existing dramatic art form. As such, it embodies the spirit of traditional Chinese culture in many ways. It is well known that Confucianism, established by Kongzi(Confucius)(551-479 BC), provided China’s mainstream state ideology since the Han Dynasty(202 BC-220 AD).

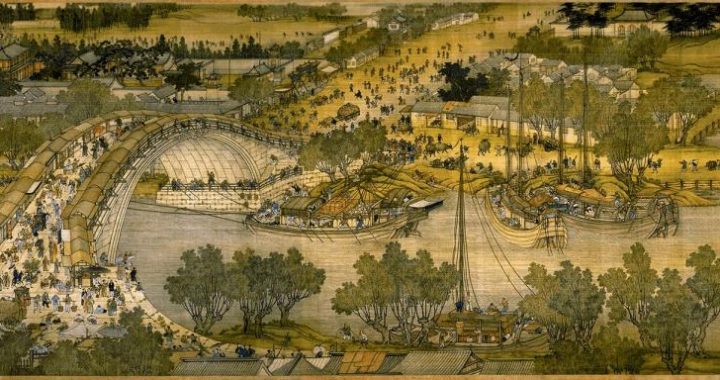

The systematic enforcement of Confucian ideology deeply influenced the attitudes and daily life of the Chinese people. Confucianism was concerned with the practical workings of society, viewing all things from a humanist perspective. The Confucian standard of morality was enforced in both government and private life, creating an orderly society in which upper and lower classes lived in harmony. The Chi-nese cultural elite had a strong sense of social responsibility. They actively participated in politics and were highly concerned with national affairs. This sensibility naturally found its way into their works of art and culture reflecting the real life. Although the Kunqu operas of the literati were formulistic in both writing and performance, they still used art to realistically represent life and society.

(Among the Nomads), performance still

Confucianism provided an important philosophical strand that runs through all Kunqu works. Kunqu operas are full of praise for exemplars of Confucian morality, including loyal and upright officials, filial sons and daughters, faithful spouses and lovers, and courageous champions of truth and justice.

Kunqu opera was a vehicle for disseminating Confucian ideology to the masses, with the goal of pro-moting a healthy and orderly society. In Muyang Ji(Among the Nomads), Han Dynasty minister Su Wu goes to the land of the Xiongnu(the Huns) to carry out peace talks. Recognizing his abilities, the king of the Xiongnu tries every means to force him to defect to their side. But Su Wu staunchlymaintains his convictions, and after nineteen years of trial and hardship, makes his way back to the land of the Han. Yueli Ji(The Leaping Carp) features an irascible mother-in-law who continually ha-rasses her daughter-in-law Pang Sanniang, finally driving her out of the house. But even then, Pang Sanniang patiently bears her grief, maintaining her filial respect for her mother-in-law despite her hardship. In the end the mother-in-law is moved by Pang Sanniang’s pure heart, and the shattered family is reunited. Jinchai Ji(The Story of the Hairpin) tells the story of Wang Shipeng(1112-1171AD and Qian Yulian, an impoverished husband and wife. After Wang Shipeng achieves first place in the imperial examinations and leaves for his post as a government official, he is unable to communicate with his Qian Yulian, leading to a misunderstanding between the two. Even so, they remain staunchly faithful to each other, and are finally reunited. In BayiJi(Eight Righteous People), the upright minister Zhao Dun of the State of Jin is betrayed by a treacherous court official.A group of righteous people, led by Cheng Ying, use their life and blood to protect the last surviving member of the Zhao family. In the end, justice triumphs.

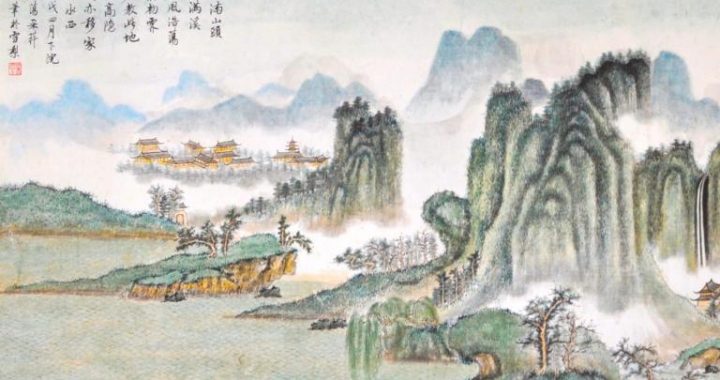

Zhao Wuniang and Cai Bojie in Pipa Ji(The Story of the Pipa)

The classic example of Confucian ideology in Kunqu opera is Pipa Ji(The Story of the Pipa)by Gao Ming.This story about the joys and sorrows of an ordinary family holds an important place in the history of Chinese drama.(See Appendix 1 for plot synopsis.)The playwright,Gao Ming,was a committed proponent of Confucian ideology.He felt that if a work did not successfully instruct its audience in ethics and morality,it was not worthy of acknowledgement,no matter how brilliant it was artistically.The characters in Pipa Ji(The Story of the Pipa)are therefore exemplars of Confucian moral-ity.They include Cai Bojie,who gives his unconditional loyalty and obedience to the emperor and his parents;Zhao Wuniang and Miss Niu,who comply with every stricture of feudal morality;and Zhang Guangcai,who selflessly helps others.Gao Ming hoped that by taking these characters as models for their own lives,his audiences would be inspired to work together to create an ideal society.

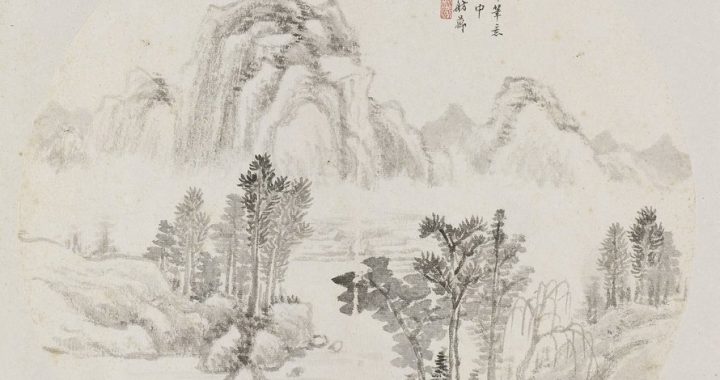

Taoism,exemplified by Laozi(580-500 BC)and Zhuangzi(369-286 BC),contributed another important component to the spirit of traditional Chinese culture.Taoist philosophy looks beyond the affairs of hu-manity and society to take a more cosmic perspective,holding that all things in the world are embod-iments of a universal whole and that everything should work with natural forces.Taoism transcends the practical in its approach to the material world.This profound philosophy provided a huge source of inspiration to Chinese art.Under its influence,Chinese artists selflessly dedicated themselves to the process of creation,striving to raise their consciousness and achieve true personal liberation through their art.Taoist philosophy supplemented the deficiencies in Confucian ideology,bringing Chinese art closer to the lives of the people,increasing its emotional content,and investing it with soul.

Kunqu opera Jingchai Ji(The Story of the Hairpin), performance still The spirit of Taoism combined with Kunqu to produce a richly subjective performing art form. Every-thing on the Kunqu stage is imbued with poetic significance. The performers rely on evocative gestures and elegant singing to convey the plot and express the characters’ state of mind. No elaborate stage sets are used. Rather, the presence of houses, horses, carts, boats are indicated by simple symbolic props and the performers’ gestures, singing, and recitation. Even the passage of time is communicated through stylized movements.A few circuits around the stage may indicate that a character has trav-eled several kilometers, across several provinces, or maybe only from the back to the front courtyard.

When a character sings or rests for a while, it may indicate the passage of a few minutes,a few hours, or even an entire night. This type of stagecraft, in which the performers create a virtual world through their gestures, speech, and singing on an essentially empty stage, is very similar to that of England’s popular Shakespearean theater. In his work The Defence of Poesie(published 1595 AD), English poet and critic Sir Phillip Sydney(1554-1586 AD) discusses his views on stagecraft in the following pas-sages: you shall have Asia of the one side, and Africa of the other, and so many other under Kingdoms, that the Player when he comes in, must ever begin with telling where he is, or else the tale will not be conceived.

Now you shall have three Ladies walk to gather flowers, and then we must believe the stage to be a gar-den. By and by we heard news of shipwreck in the same place, then we are too blame if we accept it not for a Rock. Upon the back of that, comes out a hideous monster with fire and smoke, and then the mis-erable beholders are bound to take it for a Cave: while in the meantime two Armies fly in, represented with four swords and bucklers, and then what hard heart will not receive it for a pitched field. There are great similarities between the stagecraft of Kunqu and Shakespearean theater. The difference is that the lack of scenery and props in Shakespearean theater was the result of the limitations of the theaters of the day. As these conditions improved, this type of acting gradually faded away. The empty stage of Kunqu opera, on the other hand, was a vivid embodiment of the spirit of Chinese culture, and was a long-lasting element of Chinese theater.

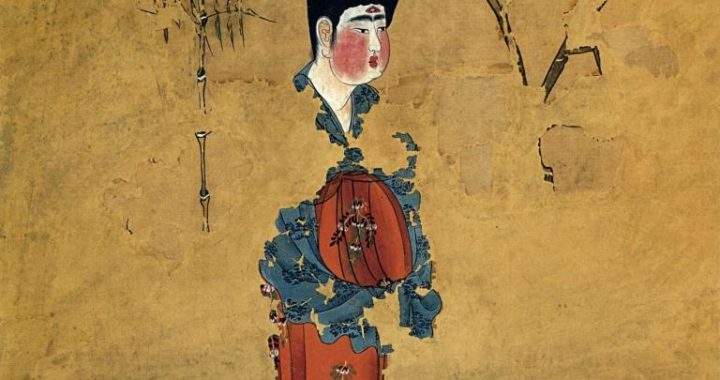

Kunqu opera Baishezhuan(The Legend of White Snake), performance still Vivid and realistic portrayals of life and society were fundamental to Kunqu opera. But Kunqu attached even more importance to its depiction of the interior world. Kunqu performances go far beyondin-consequential external details to directly grapple with the spirit of the characters, delving deep to portray emotion through a set of highly expressive, stylized gestures. This type of acting from the heart directly touches the emotions of the audience, enabling them to perceive the essence of the dramain the blink of an eye. In 1929, the great Chinese opera star Mei Lanfang(1894-1961 AD) brought his troupe to tour the United States. His performance of the Kunqu opera selection Ci Hu (Killing the Tige General) made a deep impression on American audiences. This opera tells the story of FeiZhen’e,a palace serving maid. After a rebel army enters the capital, Fei Zhen’e impersonates a princess andmarries the general of the invading army. On her wedding night, she stabs the general to death, and then kills herself. The influential American drama critic Stark Young(1881-1963 AD) was particularly impressed with Mei Lanfang’s performance. Mei Lanfang’s son Mei Shaowu paraphrases Stark Young’s reactions in his biography of his father, Wo de Fuqin Mei Lanfang (My Father Mei Lanfang):

“I noticed particularly that throughout Mei Lanfang’s performance his bodily motion is entirely har-monious and integrated. When he gestures with his right hand, not only does the movement emanate from his right shoulder, but it encompasses his left shoulder as well, so that his entire frame moves in a perfectly corresponding rhythm. The movements of his head, exquisitely balanced on his neck, are so subtle that they may be overlooked by the audience, just as we often overlook the fine lines and sur-face detail that imbue a great sculpture with life…… At one point in the opera, Fei Zhen’e casts off her crown and imperial python robe. Wearing a long white robe and blue vest with a white underskirt and long white sleeves, she flees in terror from the enraged Tiger General. As her long water sleeves flutter like the wings of a dove taking flight, you can almost hear the beating of wings. It is hard to believe that such consummate artistry as Mei Lanfang’s can truly exist. And yet every aspect of his performance is based in conventions of expression that are at once natural and highly refined. Even the position of everything on the stage is precisely determined and may not be altered…… Mei Lanfang invests these stylized conventions and symbols with such significance that they become the essence of that which they portray……. These superbly versatile methods of expression enable Chinese opera to freely ex-plore the deepest truths of the human condition and convey the pure essence of being. Chinese opera offers a unique representation of reality, affirming that it is not necessary to rely on surface appear-ances to express the human spirit.”

Mei Lanfang performs in Ci Hu (Killing the Tiger General), performance still; United States,1929 Kunqu intimately merges narrative and emotion, reproduction and representation, to refine life intoa highly stylized but beautiful performing art form. Transcending the narrow bounds of realism andformalism, Kunqu is a uniquely Asian art form. Combining truthful representation, evolved ethics, and aesthetic ideals, this ancient dramatic art represents the epitome of Chinese culture.