Poetry in Song

4 min readKunqu librettos are comprised of prose, local dialect, and poetry. Prose and dialect are used primarilyfor dialogues and soliloquies, while poetry is used mainly for song lyrics. It may be said that poetry and music form the soul of Kunqu. The elegant and mellifluous melodies of Kunqu opera were widely admired by the literati and gentry. The highly poetic and evocative Kunqu lyrics are well suited to this kind of music. The content and structure of Kunqu arias are closely coordinated, with a successful vocal performance perfectly embodying the poetry of the lyrics. Kunqu lyrics, like traditional Chinese poetry, are highly subjective. Kunqu singing therefore is highly reliant on emotive expression, much like the arias of Western opera.

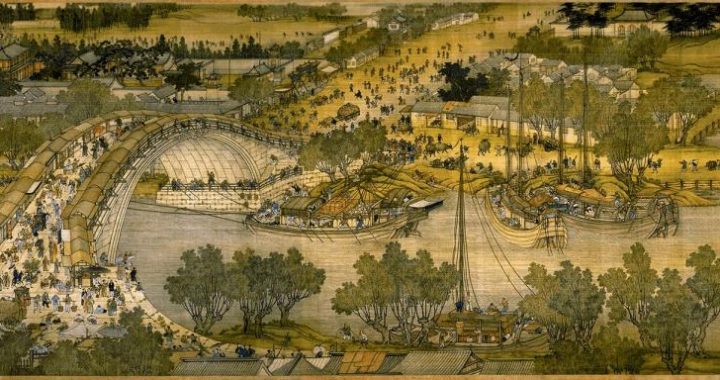

In Dan Dao Hui(Meeting the Enemy Alone), General Guan Yu (c.163-219 AD) of Shu, who is defending the city of Jingzhou, is invited to attend a feast by the leader of the army of Wu. Although he knows that his opponent plans to detain him and invade Jingzhou, he fearlessly sets out to the meeting. As he rides in a boat along the Yangtze River to the meeting, he recalls the alliance twenty years earlier between Shu and Wu and their mutual defeat of the great general Cao Cao(155-220 AD). Thinking of their former friendship, he cannot help but be overcome with emotion. The aria that he sings is a mag-nificently moving piece of poetry that evokes the audience’s deep sympathy for this ancient hero: Kunqu opera Dan Dao Hui(Meeting the Enemy Alone), performance still The waves pile high as the river flows east; my boat’s swept along by the western wind.

Ijust left the nine-towered Palace; already I’m deep in the lair of the beasts.

Boldly I bear my broadsword to the feast, as if it’s no more than a village fair.The waves still roll and the mountains remain, but where’s my old ally GeneralZhou?

All is ashes and smoke on the wind.

I sigh for General Huang Gai of my past; our fleet that van-quished Cao Cao is gone.

The river still storms as it did that day, turbulent as my grief-stricken heart.

Surely this is not water that flows, but heroes’ blood unstaunched twenty years.

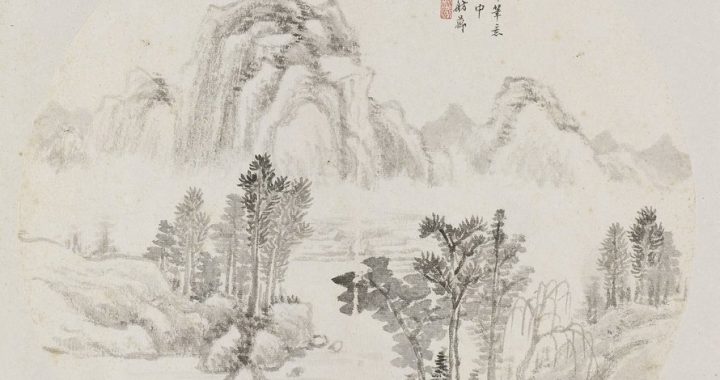

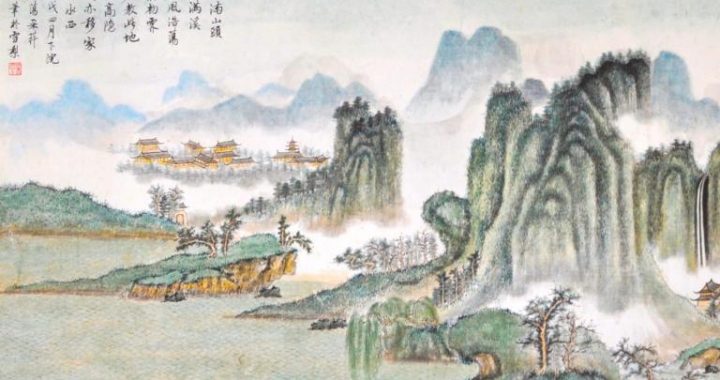

Most Kunqu lyrics are so elegant that they may be read as lyric poetry. The scene “Wen Ling(The Sound of Bells)”from the opera Changshengdian (The Palace of Eternity) offers an example. As Emperor Tang Minghuangg flees from a palace coup, he stops along a mountain road to seek shelter froma storm. Hearing the sound of bells coming from a distant mountain cabin, his thoughts turn to his dead lover, Yang Yuhuan. The gloomy weather and his grief blend as he sings the following mournful aria: Emperor Tang Minghuangg in Changshengdian(The Palace of Eternity)Hearing bells on a desolate wind, my heart goes dark and skips a beat.

Far away through mountains and trees, rising and falling with wind and rain, Bells interspersed with the drops of the falling rain, bring tears of blood to my anxious heart.

Here in this bleak and lonely place, my thoughts are drawnto my lover’s grave.

Leaves of poplar trees lashed by the rain, her soul must be so cold and alone.

Spirit lights burn above her tomb, fireflies dance in the drip ping grass.

I’m filled with remorse for what I’ ve done, alone in the world with no reason to live Hear me, beloved, the time will come, when I will join you beyond that vale.

The mountains are silent but for the bells; their sound join the tears that fill my heart.

The road through the mountains rises and falls, like my shat-tered soul that is never at rest.

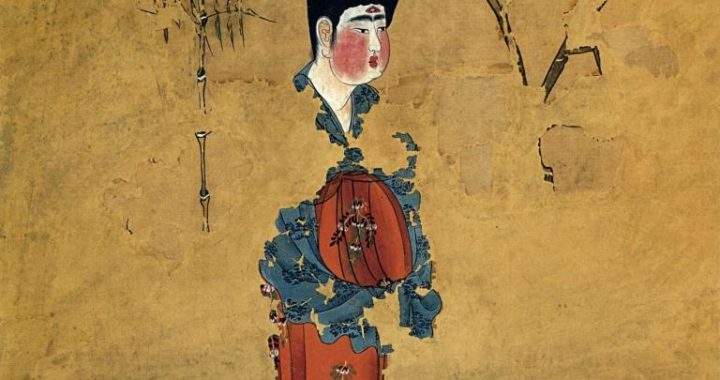

For the writers of Kunqu opera, producing poetic lyrics was not difficult. The difficulty lay in writing lyrics that would express the characters’ emotions, as well as be comprehensible to the common people who comprised the bulk of Kunqu audiences. As a result,a number of Kunqu dramatists startedto study the language of the people and write lyrics characterized by the use of the vernacular. In PipaJi(The Story of the Pipa), there is a scene in which the heroine, Zhao Wuniang, tries to eat rice husks to stave off starvation. The aria she sings serves to further the plot, while also vividly expressing her state of mind. This simple and unadorned aria, imbued with the flavor of folk music, was widely popular:

Zhao Wuniang in Kunqu opera Pipa Ji: Chi Kang

(The story of the Pipa: Eating Chaff)

I retch out my guts till tears fill my eyes, choking on chaf still stuck in my throat.

You rice husks have suffered as much as me, threshed and winnowed and cast aside Like me in sore straits, our hardships too many to count.

The wretched must eat the bitterest food; it doubles our pain and hard to swallow.

Chaff was meant to be one with grain, but winnowed it’s blown away by the wind The lowly and noble, like me and my husband, never to see each other again.

My husband, you are polished rice, lost far away where I’ ll never find you.

The wretched chaff is like me, and how can chaff relieve star-vation?

Now my husband’s gone, how can a delicate woman like me care for his aged parents.

Solely from the standpoint of its lyrics and music, Kunqu can be considered to be an outstanding type of poetic drama, on a par with all the other famous operatic forms of the world.