REPEAT PHOTOGRAPHY:FINDING THE PERFECT MATCH

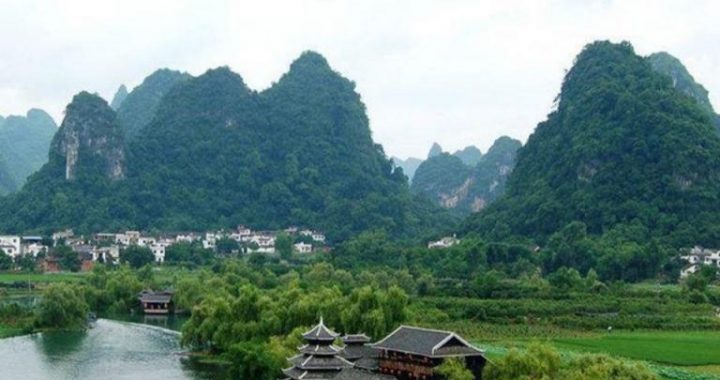

5 min readRepeat photography is simply retaking old photographs from the same photo point and of the same subject, recreating as nearly as possible conditions identical to the original scene. In practice, however, repeat photography is much more exciting than this simple definition sounds. It is especially fun in a place like Yunnan if you have any interest being a historical sleuth, uncovering interesting stories of the past, and visiting remote places that are not on anybody’s itinerary these days.

It all started in April 2001, when I moved to Deqin to start a new conservation project in the Meili Snow Mountains,a joint effort between The Nature Conservancy and the Deqin County government.I was the first foreigner to live in this Tibetan border region since the French missionaries were expelled 50 years earlier.I took with me a National Geographic Magazine article by Joseph Rock about his 1923 expedition “through the great rivertrenches of Asia,”the very country in which I was now living. On weekends, I started hiking around Deqin and relocating the exact spot where Rock stood eight decades before and photographing a modern version of the same scene. It was a technique I had used in the mountains of Idaho in 1977 during a summer job in college. As I started to compile more and more of these repeated scenes, they collectively started to reveal a history about environmental change in Deqin that was previously unknown.

Given the useful information gathered from this small sample around Deqin,I embarked on a more systematic search for old photographs from throughout northwest Yunnan. This led me to sometimes obscure library archives in the United States searching for published sources and to collections of unpublished images in places like Washington D.C., London, Edinburgh, and Vienna. In the end,I compiled almost 1,100 images taken by 42 photographers that could be repeated. The criterion “could be repeated,”means the image contains enough of a view of the landscape thatI would have a realistic chance of finding exactly where the photographer stood. Sadly, that meant that I had to exclude images of people, interiors of villages, close-ups of flowers or vegetation where there was no reasonable chance of relocating the exact photo point. That is not to say that all landscape photo points are easy to relocate. Some photographers provided enough caption detail to make relocation easy. Joseph Rock left amazingly detailed captions, which was fortunate, because half the historical collection was his photos. But most others left only vague location references, at least in the published captions.

There were two essential elements to finding these historical photo points, knowledge of the geography and reconstruction of the historical itineraries.

As to geography,I had the enjoyable advantage of living, working, and traveling widely around the region for several years. With personal knowledge of the geography, plus that of my Chinese colleagues,I could easily map out trips that brought me within the general vicinities of the old photo points. Once there, the scenes often pop right out at you in the vertical terrain and open countryside that is northwest Yunnan. Sometimes the scenes are soiconic even today that I knew instantly where the photo had been taken. It was only a matter of finding exactly where previous photographers stood.

The other element that became critical was reconstructing itineraries of the Western explorers: the routes they traveled and the time of year they were there. Itineraries could often be reconstructed from their writings, because many wrote in a chronological travelogue style, but the best sources were maps that some used to complement their expedition narrative. Joseph Rock again excelled at this with his maps for the U.S. Army Map Service. No matter how rudimentary, maps provided a key piece of information in relocating old photographs. The most difficult aspect of deciphering narrative and mapped itineraries was reconciling the diversity of ways that the French, German, and English speakers represented place names. Difficulty arose from several overlapping factors:(1) place names were in the local ethnic language, most of which had no written form;(2)sometimes there were also Chinese names given to the same places; and (3)there was no standardized way to represent all of this with the Latin alphabet.

Eventually I got a knack for it, however, by using multiple sources and understanding that the French used many vowels in their transliterations, the Germans many consonants, and the English somewhere in between.

Armed with old itineraries, historical maps, and knowledge of the geography,I organized expeditions to relocate sets of images in well-defined areas. In some cases, the scenic areas of yesteryear have been developed into tourist sites, with their scenery well publicized. Those were easy to relocate.

But most often we ended up in out-of-the-way places, traveling to small villages that used to be on the main caravan trails, but became isolated when vehicle roads were constructed on different alignments. Upon entering a village, we consulted with the locals for a couple of reasons. Foremost was that they knew where the old trails were and often recognized the scene in the old photograph. They could easily lead us to the photo points. Second, they were also in the best position to tell us about the history of the village and help interpret the environmental and cultural changes we could see between baseline conditions of the original photos and modern conditions today.

We especially sought out village elders to piece together the land use history around the village.This local knowledge was later used to complement scientific understanding about what we were seeing.

By the end of my last expedition in June 2005,I was fortunate enough to have rephotographed 420 historical scenes from all corners of the region and ranging in elevation from 870 meters (2,850 feet) to 5,047 meters (16,558feet).I stood in the same place as 20 photographers who had visited Yunnan between 1895 and 1949. Along with each photographic sequence,I retell a few of the thousands of stories I collected about history and change in a place many call Shangri-La.