The Custom of Sand-skating at Dunhuang

6 min read“Custom: On the 5th day of the 5th lunar month, ladies of the town climb up the high dune and then slide down together, making noise as loud as thunder; looking when dawn comes, you find the slope as steep and smooth as usual.”This is what is described in Dunhuang Lu(Record of Dunhuang) under the entry of “Mingsha Mountain”, a custom of sliding on steep sand slope in ancient Dunhuang. It is watched up to the present. On the Dragon Boat’s Day of 1990, Dunhuang Folk Customs Society organized a sand-sliding exercise and a loud noise did come from above, measuring at 67 decibels. The athletes felt that the valley shook with it and they felt as if being tossed up.

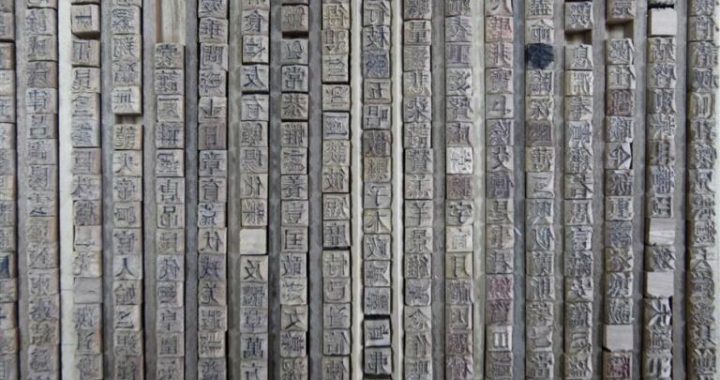

This is only one of the traditional customs of Dunhuang; others include diet, dress, architecture, travelling, wedding, funeral, education, faith, social rituals, and so on.A1l of these can be found in the Dunhuang manuscripts. The following is a brief introduction to some of them.

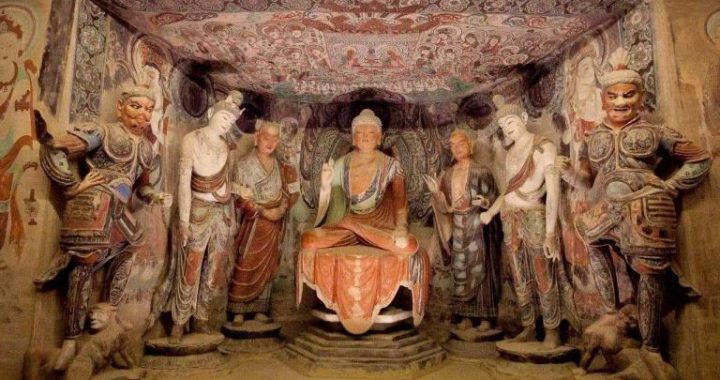

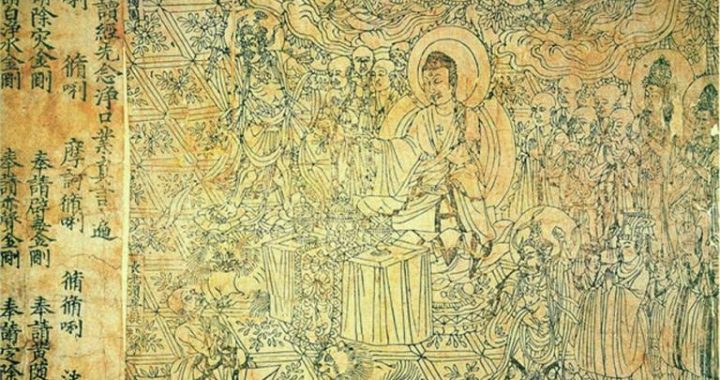

Devil driving is undoubtedly the most prominent folk custom in Dunhuang. It is a formal activity since the ancient times held to be supposed to drive away the devil which causes plague. Participants wear masks and disguise themselves as various characters, including ghost-catching Zhong Kui, the divine beast Baize, the General Keeping the Book of Life and Yamaraja, and all sorts of ghosts and monsters, as well as ordinary people. It is composed of chanting ballads and giving performances, unique and flourishing.

The custom of forming associations was rather popular among people of Dunhuang, with participants coming from all levels. Some people, in particular, organized private associations out of free will or set up associations by luck. Some associations were formed by monks; some by women. Some were formed by people inhabiting the same lane,e.g.S.2041 is about an association set up by “neighbors of the west alley of Rufeng Lane”during the years of Dazhong; some were formed by ranks,e.g. association of soldiers in P.4063; some by people of the same trade, like irrigators and carters. There were mini-associations of two or four members; and there were associations as big as 90 people. The rules were established and observed by all the members. Every member was equal before the rules. There was no strict hierarchy of a national organization. All the members in charge of something, including the head, were elected by their members. They were different in the division of work, but not in a relationship of rulers and the ruled.

All events were kept in record and the business was open to all. These associations kept the tradition of mutual assistance of primitive communities, bore the intense colors ofConfucianist morality, and engaged chiefly in religious activities of sacrifice andmutual assistance at funerals. They held together and helped each other in fighting against disasters and difficulties that could not be resisted by individuals. It reflected the Chinese spirit of saving people from grave danger and the tradition of mutual solidarity.

The customs of wedding in Dunhuang were rather rich in content and have providedus with complete data concerning the ancient wedding procedures. They reflect the overa11 look of wedding, and can be regarded as the database of wedding procedures of the Han people in China. The most prominent examples are zhangche (blocking wedding chariot) and xianifu (challenging husband). The key of the former custom was for the bride to respond to embarrassing challenges of young men, both throughchanting Erlangwei folk songs or poems, and closed by the bride handing out gifts.

This custom of folk wedding game was soon followed by the imperial court and officials. In the second year of Jinglong (708) in the reign of Emperor Zhongzong of the Tang, Prince Anle was remarried to Wu Tingxiu.

At the wedding, the queen’s guards of honor were borrowed and royal bodyguards were employed to make the ceremony pompous, and the bridegroom was told to stop thechariot. This means that the custom of blocking wedding chariot was very popular in the Tang and Five Dynasties and it was a wedding culture that appealed to both refined and popular tastes. And Xianifu was similar to the story of Su Xiaomei Repeatedly Challenging Qin Guan in later times. The bridegroom was frequently disguised as a successful candidate who had just passed the provincial civil serviceexamination and put up at the home of the would-be bride whose family would try with cross questions to find out his identity and assess his learning. And the result was such interesting works as Xianifu ci-poem which makes vivid and dramatic description of some links and procedures of wedding.

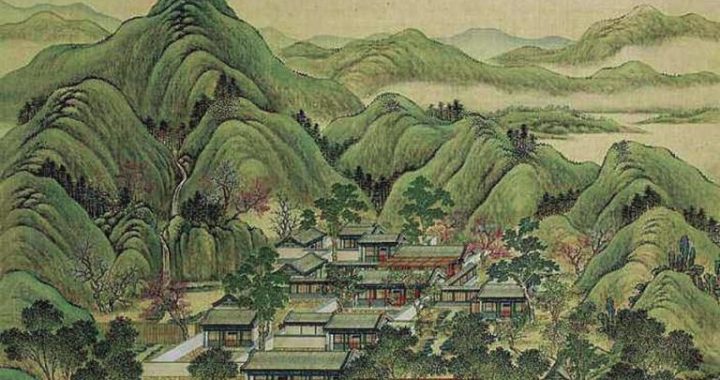

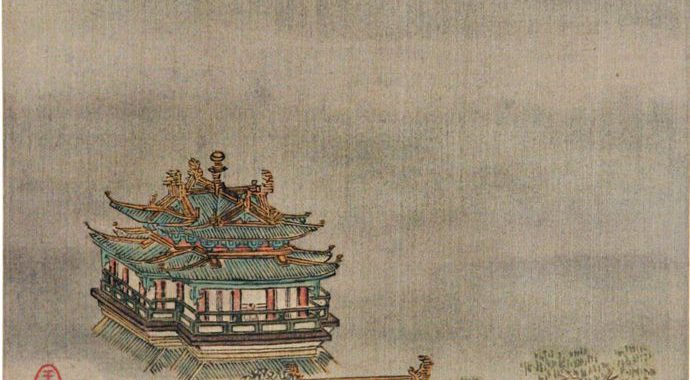

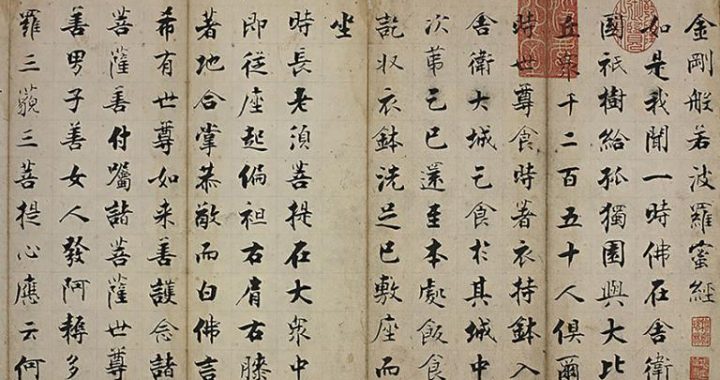

Dunhuang topographical documents are mainly Shazhou Dudu Fu Tu Jing (Atlas with Inscription of Area Command of Shazhou Prefecture), Shazhou Yizhou Di Zhi (Gazetteer of Shazhou and Yizhou Prefectures), Xizhou Tu Jin (Atlas with Inscription of Xizhou Prefecture), Huichao Wang Wu Tianzhu Guo zhuan (Biography of Monk Huichao’s Travel in Five Indian Kingdoms), Zhu Dao Shan He Diming Yaoltie (Outline of Mountain, River and Place Names in Various Routes), Gua Sha Gu Shi Xi Nian(Annalist Record of Ancient Events in Guazhou and Shazhou Prefectures) compiledin the Tang and Five Dynasties, mostly having never been seen or heard of. They have reflected the outlook of the works of local topography in the flourishing period of record compilation in the Tang and Song and occupy an important position in the history of local topography in this country.

Taking as an example several manuscripts of Shazhou Dudu Fu Tu Jing, they couldenable us to see the original appearance of the Tang’s illustrated topography.

Compared with Si Chao Tu Jing (Atlas with Inscription of Four Dynasties) and Yanzhou Tu Jing(Atlas with Inscription of Yanzhou Prefecture) in the closing years of Northern Song, the earliest exant illustrated topography, they are earlier by four centuries. This has greatly broadened our horizon, and based on them,a certain number of errors and fallacies in this field may be corrected. Detailed in narrationand rich in content, they have preserved much precious data of history and proved to be of considerable importance to the research of history, society, geography, communication, economy and religion in Dunhuang and even in the border area of China’s northwest in the Tang and Five Dynasties.

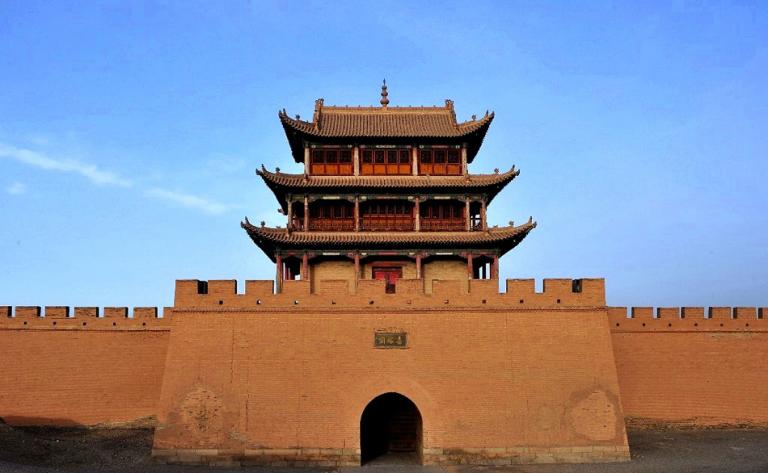

For example, the description of the towns of Dunhuang prefectrre, Hecang, Xiaogu, Shouchang, Guazhou, Changle, and Xuanquan, ancient Great Wall, ancient fortresses, and the passes of Yangguan and Yumenguan, as well as Shicheng, Tuncheng, Xincheng, and Putaocheng in ancient Kroraina is richer and more precise, therefore, extremely helpful in the textual research of the location of ancient townsites and further in the exploration of the origin and layout of townsites and the rules of formation and evolvement of town system in the arid area of the northwest. For example,a special entry “che kieou so yi”in P.2005, describes in detail the location and establishment of courier routes of all relay stations under the control of Shazhou;P.5034 records 6 routes to all places from the Shicheng town of ancient Kroraina with a detail description of their directions, mileage, availability of water and grass, road conditions, seasonal restraints, and so on. These data are more specific and lively compared with Di Li Zhi (Classified Record of Geography) and Wai Yi Zhuan (Biography of Alien Barbarians) in orthodox history; therefore, they have provided us with precious data in studying the ancient routes of the SilkRoad and changes in natural environments along these routes and opened a new sphere of research in geography.