The past, present and future of Wuzhen

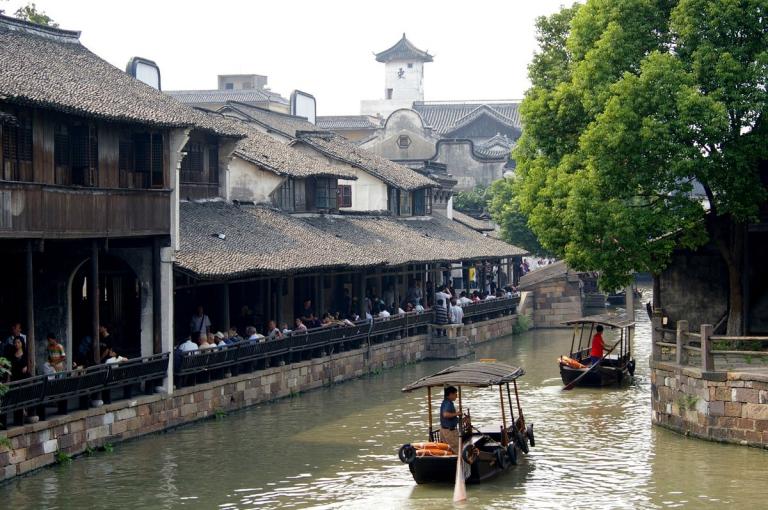

12 min readWuzhen is a fascinating town. It is also attractive. It does not matter if its faded beauty has had to be recovered as the restoration has been near faultless. There is nothing intrinsically superior about a place like Cambridge which endures constant small repairs to the sudden total restoration of Wuzhen. What matters is that the mending is done honestly and well. In this respect Wuzhen is above reproach. The canal boats, the canals themselves, the timber houses, the up-and-down pedestrian bridges, cobbled lanes, temples, and the places to eat and drink are irresistible. Those that would criticise its transformation need to remember that the alternative was a not-so-slow decline into oblivion.

The town offers, however, more than an intellectually undemanding piece of eye-cand’. It is more than a pretty but vacuous lady who is lost to the mind soon after moving on. It offers more because the new governors of Wuzhen provide a taste of Chinese culture which should linger with the visitor longer than the mere physical images.

Wuzhen holds out the opportunity to the Western and Chinese visitors alike of being better informed about China. During their visit they might have learnt a little about the life of Prince Zhaoming, son of the Emperor Wu around 500, as well as the staggering longevity of Chinese culture. This cornerof Zhejiang province has been an astonishingly fertile ground for literature.

So fertile that it includes three giants of twentieth-century Chinese literature, Mao Dun, Mu Xin and Kong Lingjing, who were each born, and lived part of their lives, in this water town. Other literary heroes, Lu Xun from Shaoxing and Xu Zhimo from Haining, dwelt barely a stone’s throw away from Wuzhen.

It is remarkable that a town so small in a country so vast could have producedsuch outstanding writers of their stature. The label ‘ Land of Plenty’, so easily attached to Wuzhen, is merited not just by its silk, rice, fish and tea but also by its cultural riches.

An acquaintance with Prince Zhaoming’s story might also have led the visitor to a little understanding of the ancient states of Wu, Chu and Yue which fought each other before the unification of China over two thousand yearsago. Such fighting made life difficult for the people of Wuzhen. Encouraged perhaps by the visits to Mu Xin’s museum or the home of Mao Dun, the visitor might subsequently be tempted to read The Shop of the Lin Family or Mu Xin’s An Empty Room. They are well-written pieces of literature. Sentences are short. Imagery is vivid. Their realism memorable. The stories tell of the good and the bad times in Wuzhen.

Revolts such as the An Lushan during the Tang in the eighth century or of the Taiping in the nineteenth century created much hardship for many, including the people of Wuzhen. The flooding of China with opium by the English, and Japanese cruelty during their invasions also brought huge suffering.

Such troubles did not bypass Wuzhen. Mu Xin wrote of how his father’s elegant concubine fled from Shanghai to Wuzhen only to be brutally murdered by the Japanese. Mao Dun described the opium-addicted Chen family of Wuzhen; a decent family, whose troubles must have been bad indeed if the head of the family was driven to take the toxic drug. There were not many of China’ straumas which the town avoided. This was because it lies at the heart of the Yangtze River valley, one of the richest cultural and economic areas of China.

Through Wuzhen so much of Chinas fascinating story can be understood.

Wuzhen’s museums provoke thought. Foot-binding was a repulsive and recent practice. The museum reminds how easily one section of society can persecute another. The museum also places foot-binding in the context of women’s historical position in Chinese society. Understandably modern Chinese people are ashamed of this practice, but not on the grounds thar China alone abused their womenfolk. There are still some equally cruel practices imposed on women in other parts of the world. Abuse against women comes in many forms.

In 2017 there was widespread shock in England at the dress codes imposed on women by some companies, such as the requirement to wear high-heeled shoes, make-up and particular clothes. Chinas version was unique in style and cruelty.

However, women in many places of the world still have to conform to male-dominated values. This museum raises such thoughts.

The Wedding Museum also educates. Wuzhen museums touch on the rituals which reached into ever corner of Chinese society, be the ritual the cosseting of a Wuzhen silkworm or the journey of the xichuan, wedding party boat. Ritual is all, from the time of Confucius to the present day. The museum also reminds how marriage, family and children have caught the attention of the government. Same-sex marriage, the marriage difficulties faced by the guanggun, or’ bare branches, the profound consequences of thirty-six years of the one-child policyand the presures on young men to provide homes, cars and the elusive parking space are topical isues. In different ways each is raised by the museum’s exhibits. The past is ever entwined with the present. The wedding bed may notbe quite so central a part of the wedding trousseau, but wedding rituals and these other pressures on the modern Chinese bridegroom remain.

The abundance of silk, tea, rice and fish ensured that there were many good times interspersed with the bad. However, economic change since the nineteenth century had left Wuzhen with a set of economic problems which could not be defeated as could be invaders. Invaders move on, tire of their savagery or are defeated. Economic decline can be a more permanent and destructive force.

Silk growing and filature passed to Yunnan province in the southwest, an area of cheaper labour with a more appropriate climate. Transport along the Grand Canal was trumped by the railway. Local people were left with the option of subsistence fish and rice farming, or emigration to the urban centres. Many joined that tidal wave of emigration to the cities. It is claimed that all fifty of Wuzhen’s factories closed in the years following the 1937 Japanese invasion; only five of them reopened. In consequence during the 1990s neglect from poverty disfigured or blocked Wuzhen’s waterways. Bridges fell into disrepair, the paving stones of alleyways cracked and timber buildings rotted. There was not much’ candy’ or beauty left for any eye to feast upon in Wuzhen.

This was the situation from which twenty-first-century Wuzhen was rescued. Some critics, usually Western journalists who are not thinking too deeply, suggest the town has lost its soul. It has for them simply become too perfect and needs more local people and detritus for authenticity. These are the similar thoughts incidentally that sometimes disturb the leaders of Cambridge University colleges. As the colleges’ intellectual mastery is surpassed by the interdisciplinary success of the university’s faculties, masters worry that their colleges are becoming little more than theme parks for visitors.

Wuzhen’s critics object to the fabric of the town’s near perfect appearance, near’ because happily it is still possible to spot a few signs of normal wear and tear. Pretty but fake’ was one such not very profound comment from a Westernjournalist. These critics forget that there was no alternative. Saving Wuzhen required a very significant investment. An expensive restoration of an attractive old water town needed a business framework which would reward investors.

Wuzhen’s mix of cultural history, contemporaneous theatre and the internet has met that need. Flesh has been added to the framework.

It could be tempting for some to see Wuzhen as a skilfully finessed Disneyfication, clever tinkering with a historic fabric motivated by developer’s gain. The transformation is actually much more interesting. This is an A la Recherche du Temps Perdu’ experiment in a country obsessed by taking its place as a world leader but aware that so much of an immensely fascinating culturehas been lost through a mixture of carelessness, frequently changed capitals, wanton vandalism and the recent movement of hundreds of millions of people from rural to urban living. The reclamation of Wuzhen is a magnificent project and should be see in this context,a context wherein China seeks to face forward without forgetting its past.

The old and the new in Wuzhen are delightfully entwined. Symbolically, prize-winning modern buildings stand close by a timber-built old water town. It also represents the new China in another way, the China which seeks economic progress, sanctions economic gain and provides legal framework for businessenterprise. The resuscitation of Wuzhen took place through local government cooperating with private businessmen. These conditions were missing in the late nineteenth century when China’s Qing political class fatally distanced itself from society. It failed to exert control from the economy. Wuzhen shows how China’s socialist market economy can work well.

Preservation of every country’s past culture is a universal obligation. To the economic decline of Wuzhen, Chinas political traumas ensured the town’s past had been neglected during the last quarter of the previous century. Not for Wuzhen the privilege of the Cambridge approach whose ancient buildings take it in turn to be smothered with plastic, scaffolding and then repaired. Cambridge bricks, stone and clunch are constantly restored, building by building; the town has been, and remains, rich for centuries — it never expereinced the difficulties which Wuzhen did in recent times. Preservation of Wuzhen required ‘”The BigProject’ approach at which China so often excels. The outcome is admirable.

Indeed the reclamation of Wuzhen from the clutches of terminal decline is simply the Chinese way of doing things. Since the traditional Chinese building material of timber rots, their ancient buildings have often been rebuilt several times on the same site to the same specification. This is, after all, exactly how ancient English churches evolved; the fifteenth-century stone church buildings which exist today have often replaced rotten Anglo-Saxon timber churches on the same site.

Generally in China these re-constructions have been faithful to the original design. Wuzhen may be particularly clean and its homes in particularly good condition, but it is again as it once was. The English, particularly the Victorians, often took a different, almost vandalistic, approach. In the nineteenth centurythey discarded centuries of adaptations to buildings by ancient occupants tocapture a past which they imagined existed. Cambridge has two very famous and delightful eleventh century buildings in the Round Church and Jesus CollegeChapel. However the historical continuity of each building was substantially broken by the Victorians. No Chinese journalist would ever consider writing of these two most attractive buildings as pretty but fake’ but a case could be made for exactly that proposition. Western criticism of China is often ill-considered.

Wuzhen’s internet hotspots may be legion but there are no power cables or old-fashioned telephone lines above ground. Neither has the occasional modern tile been left to disturb the peace in the middle of an old roof. The attention to detail is impressive. The inventiveness of Chinese architecture can be understood in Wuzhen. The cleverness of the Dougong timber structural support reducing Chinese walls to mere bit-player roles, the meaning of the roof charms and understanding why those high stone blocks at the threshold of a home must bestepped over are interesting pieces of knowledge to acquire. This can educate Chinese and English alike.

Museums to complement the places of religion are a sensible offer to the visitor. Decoration of linen cloth, the unravelling of the silkworm’s cocoon and complex weaving machines are as fascinating to visitors made ignorant of such processes by modern clothes stores, as a farm visit must be to city kids brought up on a diet of McDonald’s food. Similarly the Coin Museum plays a role.

The place of coins in the era of bitcoins and virtual money-substitutes needs remembering. Knowledge of ancient marriage customs in a time when young people use dating websites is equally important. It is also simply a good thing, in an era when the world’s cultures are converging towards an indistinguishable greyness, that past variations in culture are retained and celebrated. Engagingly Wuzhen does not deal with the past alone.’ Internet Wuzhen’is almost a curious juxtaposition for an ancient water town in the Yangtze River valley. This connection to the pervasive virtual world has bought some excellent modern architecture. The Mu Xin gallery and library, the theatre complex and the conference centre are acknowledged as world-class examples of twenty-first-century architecture. Again this provides a fine analogy to the ancient university town of Cambridge. The glare thrown off by its finest and most ancient buildings can leave the visitor unaware of some outstanding modern architecture the university has commissioned. So too in Wuzhen, but its modern architecture, as in Cambridge, is well worth seeking out.

The activities within the Wuzhen buildings are also relevant. Ironically provincial governments are on the one hand trying to hold back the virtual world by assisting the survival of the book, while on the other hand promoting the internet.A quarter of the costs of new bookshops in China can be covered by state subsidy and, in fact, the march of e-books is being checked in China as it appears to be in the West. Judging by the number of readers readingbooks in the amphitheatre-styled seating of many Chinese bookshops, there has been some success. Theatre too is fostered in Wuzhen through its annual festival which may yet provide another link to Cambridge. In a number of places around the town arts and crafts weaving and decorating practices are demonstrated with children encouraged to participate. Wuzhen tries hard.

Competing with the internet may be the challenge to the book world, but it is to shape the virtual world that the World Internet Conference has taken place in the town each year since 2014. Undeniably the internet provides wonderful opportunities for the hungry mind to soak up information which was simply inaccessible to most people before. No longer is knowledge the preserve of the university professor with special access to libraries. Knowledge has been democratised. This is a wonderful development. Anyone seeking knowledge can quench their thirst at their personal computer. The internet has, however, brought deadly serious problems. Since 2014 these problems have become both more intractable and multiplied. It is difficult to understand how Western countries can continue to justify their refusal to participate in the Wuzhen conference. The English policy of Splendid Isolation in the nineteenth century, American isolationism in the 1930s proved to be bad policies domestically and internationally. Engagement is always preferable.

Wuzhen has long been blessed with good fortune. In a culture of considerable superstition, Chinese people could claim Wuzhen is a lucky place.

The spirits of its ancestors, perhaps including that of the great General Wu, must be looking after the town. Its occasional disastrous periods, when rebellion or invasion made life hellish, have been followed by good times. Good times when the natural blessings of this Land of Plenty can be used to the profit of Wuzhen townsfolk. Certainly the sensitive development of the town in the twenty-first century has been a blessing.A decaying town with a prostrated economy has been reinvigorated through tourism, internet technology, cultural events and by hosting such high profile events as the World’s Internet Conference.

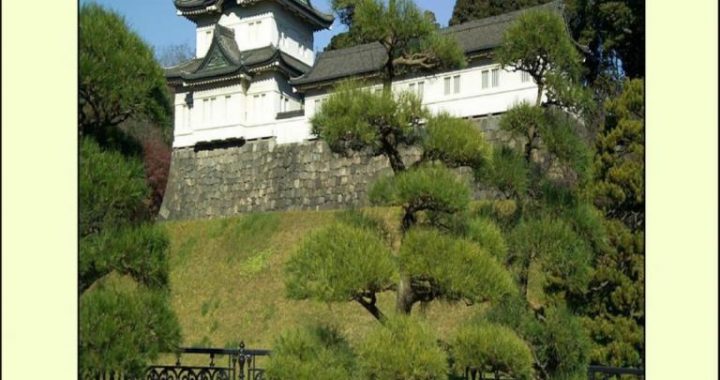

Together with Xi’ an and Shandong province, this corner of Zhejiang has been one of the crucibles in which China’s culture has been forged. The honour is not Wuzhen’s alone. Nearby are the mesmerising gardens of Suzhou, which, apart from their beauty, have such exquisite names. Some eighty kilometres in another direction from Wuzhen is the stylish imperial city of Hangzhou.

This is where the Grand Canal still begins its journey north. As in the English harbour cities of Liverpool and Bristol, the land near the canal has now beenturned into charming areas of restaurants, canal-side bars and walks. Shaoxing to the southwest also has an interesting cultural past to share. Back on the coast are the architectural marvels of Shanghai’s Bund and the hustle and bustle of a megapolis. This is a good base from which a Westerner can glimpse both modern and ancient China.

The same qualities which once attraced retired imperial bureaucrats to Wuzhen and the neighbouring area now draw Chinese visitors. China dislikes the loss of its ‘ silver, or foreign exchange, through overseas tourism as much as the English once disliked losing its sliver to buy Chinese silk, tea and porcelain.

In 2009 the State Council pronounced domestic tourism to be a pillar industry which must be developed.’ Pillar status’ is an accolade once confined to the auto, construction, mechanical and petrochemical sectors. There are big challenges facing domestic tourism even if the market is huge: the middle class section of China’s population able to afford family holidays is larger than that of the European Union.A holiday taken abroad is a statement of personal wealth which many wish to announce within their social circle. Encouraging them to holiday at home is a challenge equalled by the need to persuade Chinese toholiday at different times of the year. Wuzhen now plays a part in the tourism policy.

Wuzhen is, however, doing more than merely playing a part in China’s modern tourism plans. Like Cambridge, it is contributing to a critical needof society for history, cultural achievement and modernity to be embraced.

The late-eighteenth-century British philosopher-statesman Edmund Burke encapsulated the requirement for such an approach in Reflections on the Revolution in France(1790):’ Society is a contract between the past, the present and those yet unborn.’ The values, he argued, of a society will not endure unless the best of the past is preserved, the present accommodated and the future embraced. The Wuzhen community, however modestly, is making a commendable contribution across each of those three important dimensions.