The Path from the Great Wall to Wuzhen

20 min readThe West’s identification of the seven wonders of the ancient world would Lnever have secured approval in Asia. Given the dominance of Greek culture in European civilisation it is not so surprising that five were in Greece with the Egyptians contributing their pyramids and the Asyrians the Babylon gardens. They were indubitably Western-centric. Their selection before the wonders of the Middle Kingdom, the Zhongguo, would have mystified the courtiers of any Chinese imperial dynasty. There is great importance attached to the number seven in the West. It features 800 times in the Bible. It took their God seven days to make the world, there were the same number of Biblical deadly sins, vestal virgins, planets to be seen with the naked eye and colours in the rainbow. Even James Bond, who some believe studied at SidneySussex College of Cambridge University, was assigned the moniker ‘007’; and incidentally, he reputedly earnt a First Class degree in Oriental Studies. The number seven, gi, symbolises harmony and togetherness in Chinese culture but carries nothing like the significance it does in the West.

The World’s Seven Wonders do not attract so much attention amongst the Chinese. The focus of their children is directed towards the remarkable inventiveness of its people. Children are taught about “The Four Wonders’

which are, naturally, as sinocentric as the Seven Wonders were Western-centric.

Those four are of course the compass, gun-powder, paper and printing. The focus on the number four is unusual; other inventions -perhaps the stirrup, plough-harness, silk and porcelain -could easily have been added. It is alsounusual because four in Chinese is almost homophonous to the word ‘ death’.

It is considered a most unlucky number. Many hotels still avoid the floor designation of four in their lifts and site restaurants on the fourth floor to avoid placing guests in fourth floor bedrooms.

There are now a number of ‘ Wonder’ lists whose selections sometimes reflect mere political bias and prejudice. China generally appears once on all lists through its Great Wall and sometimes twice through the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing, which was used as the model for the Kew Gardens Pagoda in London. The contribution of Greece on modern lists is reduced to zero. The Chinese might argue that their contributions have still not been properly acknowledged.

The list of Chinese projects in contention, from lengthy walls, vast mausoleums, interminable canals, massive irrigation projects to ancient temples, is so large because they have always embraced the Big Project’ with fervour. The Chinese love Big Projects. They generally execute them faultlessly.

Their very first Big Project and the one included on nearly all lists of Wonders is the Great Wall.

A plentiful supply of labour,a determined focus on a single objective and sufficient wealth has ensured that many of their Big Projects have not just been colossal and been achieved but also have been of huge cultural significance. The Chinese tradition of autocratic government has greatly helped the realisation of these projects. The extraordinary age of many of their projects is a further astonishing feature. The vision necessary for these projects to succeed is not dissimilar to that which was applied to ‘ The Small Big Project of Wuzhen’.

Wuzhen was rescued from terminal decline through the resolve of a few determined people. Determination and vision are the two essential qualities for all such projects.

Great walls, wonders though they may sometimes be, generally bring little practical military benefit. Jericho’s Biblical walls fell after the Israelis marched round the city seven times blowing their trumpets. The walls of Rome and Constantinople were breached respectively by treachery and new technology.

Neither did the Antonine nor Hadrian walls from Roman times, built to keepthe Scots out of England, achieve much. The Scots have always come and gone as they would. The ineffectiveness in the First World War of the French Maginot and the German Siegfried lines is equally well recorded. It is similarly more than doubtful that Trump’s proposed Mexican wall will achieve much beyond deeply antagonising a decent neighbour and a short-term psychological fillip to the sort of American whose wishes are best left unsatisfied.

Neither did Chinas Great Wall much inconvenience invaders. Treachery generally enabled invading Mongols or Manchu to walk unmolested through the wall’s gates. Admittedly it may have reduced the number of challenges to the Middle Kingdom through its awesome representation of power. Psychological intimidation has long been a feature of China’s imperial governments. The Great Wall in this sense was simply the equivalent to the Chinese emperor’s army of any epoque. People in awe of a vast army, or of a vast wall, would be less likely to invade or rebel and, if a small rebellion did still occur, others might still be dissuaded from joining the revolt. The wall also served as a customs revenue point as well as to control immigration and emigration. The greatest value of China’s wall was psychological. The wall was even talked about in the West.

The Italian Marco Polo and William of Rubruck from Flanders had returned to Europe in the late 1200s; the great English savant Roger Bacon was in touch with William as both were Franciscan priests. They knew of Chinas wall. IndeedBacon proposed a wall of brass encircling Britain which would, he argued, make the country impossible to conquer.

The wall in China was certainly not made of brass. It comprised a combination of stone, rammed earth, brick and wood. Started in the seventh century BC, it has been extended, repaired and rebuilt regularly ever since. The parts of the wall which survive into twenty-first century are mostly those of the late Ming period, around 1600.

In building the wall along the northern boundary, the Ming acknowledged the reality of Mongol and Manchu control in the north of China. Their wall was stronger than previous sections, using more brick and stone. Treachery led the Manchu through the wall leading to the fall of the Ming. Great the wall may have been, but the prefix was not earnt through its defensive qualities.

Another myth, alongside the one exaggerating its effectiveness, was peddledby an English antiquarian, William Stukeley, in the mid-eighteenth century.

He determined, it is not known how, that the wall ‘ may be discerned from the moon’. Every English school child learns of, and most believe, its visibility from the moon. In the late twentieth century this was proven false but such is the awe in which the wall is held that it remains widely believed. It is, however, the longest, by far, man-made structure, and one of the best-known on earth.

The common feature between this project and others nearer to Wuzhen is the access to a vast labour pool combined with an extremely autocratic and sometimes brutal regime. After the first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, unified China in 221 BC it is recorded that 300,000 soldiers and 500,000 peasants were conscripted to build the wall along the northern border with the Hun. In the same period this emperor determined to arrange his greatest gift of all to posterity, namely his imperial mausoleum at Chang’ an. Measured against the goal of immortality which he sought, it has in a sense proved most effective.

Archeologists have brought this emperor back to life through the range of possessions which were buried with him.

The extent of the burial area uncovered in Chang’ an, meaning Perpetual Peace’, and known since the Ming as Xi’ an or’ Western Peace’, is vast. There remains far more left to uncover. Such a vast project was only possible because in addition to the 800,000 men working on the Great Wall a further 700,000 were preparing this imperial mausoleum. Writing a hundred years later, the historian Sima Qian provides these details in his Records of the Grand Historian. Soldiers, peasants, criminals from all over the empire were conscripted. Many must have died and were interred ahead of their master; likewise many are known to have died building the wall and been interred in its foundations. Archaeologists frequently find such evidence. Their death provoked one Chinese poet to write: Every brick, every stone, and every incb of mud are filled with Chinese peoples bones and sweat and blood.

Certainly more than once the labourers were withdrawn to suppress rebellion but the fact that a workforce of one and a half million labourers could be organised on two projects is astounding. The Chinese population around200 BC was 20 million. In any era the mobilisation of 7.5 per cent of the total population to undertake a couple of state infrastructure projects running concurrently is utterly astounding. Contemporaneous Chinese historians declare these figures reasonably reliable. The population of England a thousand years later was probably between one and a half and two million people. King Harolds army at Hastings, southern England in 1066-admittedly after many had been released for the harvest -was probably under 7,000. He faced the 5,000-strong army of the Norman invaders. King Harold, with his country’s survival at stake, could only raise under half a per cent of the population for his Big Survival Project. He lost the battle. At this time the Chinese were almost counting their armies in millions.

It is the ability of China to combine its vast population with determined willpower and vision that makes its projects attainable. The Great Wall and the imperial mausoleums are fine examples of this national trait. The same trait can be seen in the next two examples which both contributed to the Wuzhen story. First is the Grand Canal which stretches over 1,700 kilometres connecting Hangzhou to Beijing. In comparison the Great Wall’s maximum extent was more than 8,800 kilometres.

Similar superlatives as apply to the Great Wall should apply to the Grand Canal, the Da Yun He. It is the world’s first constructed, oldest in service and also the longest. Strangely enough it is the only man-made structure on earth which is visible from the moon, according to the astronaut William Pogue in 1974. Ironically another aspect in which it trumps the Great Wall is its service as a military weapon. In the north the dykes of the canal were broken on a number of occasions to hinder an enemy’s advance. It has won admirers as consistently as has the Great Wall, even if the achievement of its construction is less known in the West. Marco Polo was evidently familiar with its northern sections and its arched bridges as well as the southern sections near Hangzhou.

The canal was begun in the north during the Sui-Tang period around 600 to 900. The southern section which stretched down to Hangzhou was only built inthe early fourteenth century during the Yuan dynasty. This was the time when the Mongols welcomed Marco Polo. The Mongols who conquered China in the fourteenth century had more or less strolled through the gates of the Great Wall. Their capture of the key town Xiangyang on the Han River which guardedHangzhou, however, took them five years. The water of the Yangtze River basin, its rivers and the canal, proved a far better defensive network than the Great Wall in the north.

The extension southwards of the Grand Canal led to the first unification of the two most important Chinese river basins of the Yellow and Yangtze.

Hitherto the flow of rivers, both in the north and south, had made the east-west movement of people and goods in China far easier than those of north and south. The coastline provinces had always been wealthy through access to coastal trade and the gifts nature had supplied, but its inter-connectedness had been limited until the Yuan rulers pushed the canal south. The Yuan do not, however, deserve all the credit as small sections of canal, but unconnected to the main one, had existed around Wuzhen since the days of the Wu, and its nemesis the Yue, in the fifth century BC.

The easing of travel between north and south had huge implications for China, and in a more modest sense for Wuzhen as well. At the national level it permitted the full economic and political integration which a single empire required. As with the hopes behind the infrastructure transport projects of fast trains and airports in the twenty-first century, such economic structural development evened out regional disparities in wealth. Hitherto the south had been more commercially advanced. The public granary system, essential for social stability in times of shortage, also became more effective as grain could be moved around the country more easily using the canal.

It helped political and cultural integration as well. The canal’s importancecan be understood from the need the Eastern Han and Northern Song dynasties felt to have huge western extensions added to the canal in order to reach their capitals of Luoyang and Kaifeng. After the Southern Song moved to Hangzhou, Wuzhen scholars were reported heading south by canal to sit their exams in thelocal city. With the movement by the Yuan to Beijing the canal again served the scholars to take them to the distant north. Wherever examination success took them to work as bureaucrats,a home in Wuzhen became far more accessible. In retirement, or for the lengthy return home required to mourn a father, returning to the south down the canal was a simple journey.

The Grand Canal was always an epic-scaled project that had far more impact on China than the eye-catching and myth-creating Great Wall. The vision which it required, and the commitment of funding and labour, was as staggering as it was typical of the Chinese approach to ‘ The Big Project’.

At times not only were the Great Wall and an imperial mausoleum under construction at the same time, but so too would have been sections of the Grand Canal. Numbers employed on the canal are difficult to obtain. However, one statistic in the Ming dynasty survives. Their records show that 47,004 men were employed exclusively just to maintain the canal. This was virtually the same number of people who were employed to build the Olympic Park and Village at the 2012 London Games.

As for Wuzhen, where its reputation for beauty had hitherto usually depended on indirect acclaim, be it that of court officials, an artist or travellers, it now became accessible to many more. Courtiers, even an emperor, would visit. The canal had an immense impact on the town. The volume of trade in the region increased dramatically. The faster speed of moving goods and people around the country was used to justify the expense. Precisely the same argument is used to defend the expense of bullet trains or new airports a millennium later.

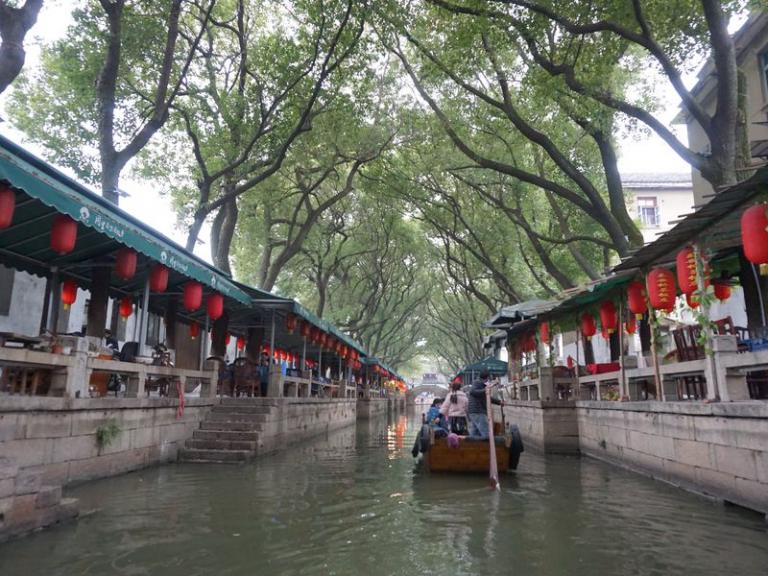

The canal passed right alongside Wuzhen. At the point the canal passes the town it is a hundred metres wide. In the twenty-first century vast barges with the length and breadth of an English coastal steamer move past. The English narrow boats, or barges need to fit into canal locks of as little as two metres wide. Used mostly by those seeking a peaceful holiday, the barges are still pulled along the quaint and attractive canals by a shire horse with long-haired hooves. The two canals are from a different world.

It perhaps took two or three days to move north from Hangzhou to Wuzhen. Its traders and innkeepers would have depended on the trade the river traffic bought to their community. Coastline aside, the canal was then the only artery of trade between northern and southern China. The canal developed the East Coast provinces of China.

The wealth it created brought also a cultural and political exchange between north and south. Wuzhen claims to have produced more successful examination candidates than any other town south of the Yangtze River. Such claims can usually be challenged but certainly there were some well known local scholars like Yan Chen in the early 1800s or Tang Long,a Jinshi who travelled to the imperial court. These exam candidates would have travelled slowly north along the canal to the imperial capital be it Kaifeng, Xi’ an, Luoyang, Nanjing, or Beijing. Success would have assured positions of authority power and wealth within the imperial government. Time and again when these sons of Wuzhenretired, they returned south to Zhejiang province and frequently Wuzhen.

This area, so generously gifted by nature, became known through the travellers passing by. The rough edges of the way of life in Wuzhen would have been rubbed away by knowledge of how life was lived in the north, in the imperialcourt and in rich places like Shandong province in between. Emperor Qianlong in the late 1700s travelled down the canal to visit the area about whose beauty he had heard so much. Imperial families liked to travel by water and the Grand Canal became a conduit of knowledge about China for the ruling dynasty.

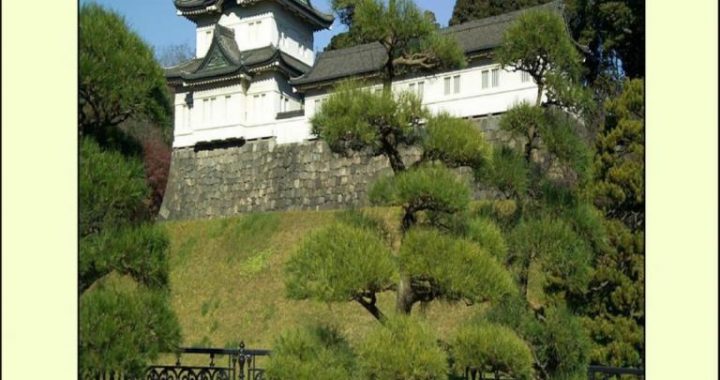

In a similar manner royal families of England, like the Tudors in the 1500s, sought a taste of their own dominion by travelling westward along the River Thames. When visiting the area near Wuzhen, the emperor admired another of Chinas grand projects, albeit one of a small scale completed long before in the late 1000’s. The governor of Hangzhou at that time,a poet called Su Shi, had used 200,000 workers to construct a three kilometre causeway across the West Lake.A more recent project in hydraulic engineering has been the Three Gorges Dam which spans the River Yangtze due west of Wuzhen. It was completed in 2012. Electricity production, flood control and increased commercial activity were all the desired outcomes from this massive project. The visibility of such projects in the twenty-first century did cause some difficulties which the constructors of the Grand Canal or Great Wall never faced. About 1.3 million people were displaced, archaeological sites were lost and the environment damaged. Big Projects in modern times inevitably attract criticism which those of the past rarely did.

The dam has also increased tourism in the region. From Shanghai, through Nanjing, Wuhan and then using the ship-lift, Chongqing can be reached.

Once more, as when Wuzhen profited from the thirteenth century court of the Southern Song being in Hangzhou, the entire Yangtze River valley has benefitted from the increased economic activity. The Wuzhen area again benefited.

Besides these projects, that of Wuzhen is a mere ephemeral Will-o’-the-Wisp,a flickering candle of near nothingness. Yet it still required the vision and commitment which the Chinese generally apply to its projects. There are significant differences to this Big Project of course, and not just in terms of scale. Twenty-first-century Wuzhen for example was partly developed by private money. However, little of significance is done in twenty-first-century China without implicit or explicit approval from officials at some level of government. Since its resurrection the government use of Wuzhen alongside its private tourist development make it a classic example of how Communist socialism works in China. The initiative and the majority of the investment may have come from the private sector but the state has been closely involved.

For outsiders at least, the project to rescue, restore and to provide a future for Wuzhen began in 1999. The business vehicle was Wuzhen Tourism Co Ltd (WTC). This private company is led by Chen Xianghong who was born in the town. It is now a large travel service group whose shares are held by China Youth Travel Services(CYTS), Tongxiang City government and a private equity firm, IDG. IDG were able to increase the value of its original investment tenfold by the time it sold its shares to CYTS in 2013. This investment profit is certainly one measure of the Wuzhen project’s success. CYTS now owns 66 per cent of the company with the balance still held by the Tongxiang government.

Chen Xianghong has won the top Asia Pacific Heritage conservation award for the reconstruction work he inspired.

WTC embraces the language of corporate speak and aspiration which is also over-used in the West. Its PR bumf records the wish that it objectives will be ‘ surpassed through foresight’ and that its people-based orientation foster its core competitiveness’. Mocked as such phrases of ‘ business speak?

should be, the venture has proved successful. Since 1999 the number of visitorshas grown to five million annually. The fortunate ex-shareholders at IDG could also speak for its financial success.

However little known for the moment Wuzhen remains in the West, it is now decidedly well known in China. It is rare to meet someone in China who has not heard of the town, who thinks it is attractive and who then mentions that it is firmly inscribed on their ‘ Wish List of Places to Visit’. This suggests its present success will continue.

The evidence of its success should start with the place itself. Cynicism ina Western visitor may be primed through absorbing such references as those of the London Daily Telegrapb newspaper to a ‘ sanitised village, or Time Out’s use of the term ‘ commercialised’ to describe the town. Another refers to its soullesness’ since few local people now live there. Yet all three journalists at the end of their articles recommend strongly that the place be visited. Wuzhen, they record, is undeniably pretty, best at night but just as picturesque in day time’. Another journalist records that they wished to find the whole thing ‘ impossibly cheesy’ but concluded that this audacious project has been brilliantly executed’.

New Wuzhen does look tremendous. It postures convincingly as a prosperoussmall Chinese water town, one to two hundred years old. The absence of any buildings in disrepair, of a town’s detritus, or of normal human disorder may disappoint some but it does not in any way vitiate the experience. It may even be that some controlled deterioration has been deliberately introduced as there were, in 2017 in any event,a number of large expanses of white walls which needed’a lick of paint’. The occasional imperfection is comforting.

Twenty-first century critics of Wuzhen forget it has been recreated before.

Recreation is the Chinese way; restoration, exemplified by Cambridge, is the English way. Each have their strengths. Usually recreation in China followed destruction during periods of national disintegration before dynastic change or perhaps through some natural disaster such as flooding in the Yangtze valley. The most recent resurrections were after the sufferings caused by the Taiping rebels and the cruel Japanese invaders. This twenty-first century re-creation isdelightful. It is not quite a Venice of the East, but Wuzhen captures a little of the Venetian charm. Wuzhen was a retreat for the rich, as well as a town where others made a tough living from silk, rice and the river trade. Venice after allwas the lagoon-strewn capital of a once powerful European state, with buildings and art of stupendous quality, which had despatched Marco Polo to Hangzhou.

Yet perhaps both Venice and Wuzhen have confronted the same nightmares of choosing between ‘ restored’ beauty and decay, of fairytale restoration ordystopia, and of needing to find those with willingness to fight decline andneglect. They now share the bane of success in modern times, namely excessive numbers of visitors. Weekend visits in tourist seasons can already harm the Wuzhen experience; in that respect Wuzhen has quickly caught up with itsneighbour Suzhou. Suzhou with its wonderful gardens, alleyways and little bridges is simply to be avoided in times of tourist surfeit during national holidays. At the wrong time the visit to either Suzhou or Wuzhen can be anincredibly claustrophobic experience. Due to the Chinese habit, shared with the French in Europe, of taking holidays simultaneously the timing of visits to Wuzhen requires attention. Wuzhen is ahead of Venice over handling visitor control. Visitors to Wuzhen pass through turnstiles at a single point and are limited to 15,000. The average 13,000 suggests the town is busy throughout the year. Summer visitors on a single day to Venice are up to 70,000; it is admittedly a bigger place but they continue to dither over whether to introduce controls such as Wuzhen have installed.

The markers of Wuzhen’s success are numerous. For example the town now has striking and well designed modern architecture. The museum and memorial to the writer Mu Xin built alongside a reed-and-lotus-filled pond is delightful.

The approach across a footbridge, its submerged water garden and the eight exhibition rooms themselves perched above the water is analogous to the homes in Wuzhen itself built on stilts above the water. There is the Lotus-themed theatre building and the conference centre. It was clever as well of the Wuzhen Tourism Co Ltd to employ outstanding architects.

The old architecture of the Qing period has been perfectly restored.

Nowhere do modern materials sneak into an ancient high gable,a party-wall, an alleyway,a shop front or a bridge buttress, as they do on occasion in ancient Cambridge. Either original materials have been salvaged or replacements have been sought out with great care. Neither has the disease of multi-coloured neon lights, so overused in most Chinese cities, ensnared Wuzhen. Bridges, alleyways, and some riverside homes are lit at night but discreetly and in only white or yellow lights. Such resistance to the social norms of modern China deserves praise. Even the resistance of Cambridge University to such lighting is crumbling; in 2017 to celebrate its 600th birthday the vast tower of itsUniversity Library was disfigured with flashing multi-coloured lights. Alsoabsent in Wuzhen are overhead power lines, television aerials and intrusive satellite dishes, even if there must have been telegraph poles here and there before the project began.

The old quarters are now kept particularly clean. Despite the remarks of some Western journalists this should not be considered so remarkable. The streets of many Chinese communities are swept clean to astonishingly highstandards. There is an army of young-retired folk to complete such jobs in China, as there is to police busy pedestrian street crossings in nearby Shanghai.

The money they earn supplements their very poor pension payments and doubtless such occupation supports their physical and mental health. People were moved out of the West sector of the old Wuzhen town. No residents are left beyond those running the small hostels. Homes in eastern Wuzhen were offered to the displaced and if the detritus of normal life is sought as proof of human inhabitation it can be found there. There are plans for the eastern, then northern and southern parts of Wuzhen to be developed.

Another measure of the success of Wuzhen has been its selection since 2014 as the home for the annual World Internet Conference. President Xi visited one of the internet gatherings and was photographed with a broad smile strolling through Wuzhen’s alleyways. Each year one of Chinas top leaders attends this conference and is pictured in Wuzhen. This provides an immense fillip to the visibility of the town. An annual theatre conference is hosted as well. The founding of a long-term arts festival by a private company suggests that themotivation behind the revival of Wuzhen is not money alone. The town is being filled with the culture modern life as well as that of the Qing from the past.

Criticisms are made, but they generally come only from prejudiced Western visitors. Wuzhen reminds of other delightful restored places such as Lijiang in Yunnan province, near to the Tibetan border.A hint at any criticism to a guide there about the town’s excessive commercialisation draws an immediate response.

The town was dying before its makeover. Life from farming for Lijiang villagers in the Himalayan foothills was torturously hard. Selling trinkets to tourists and taking them hiking in the hills is much easier. Rich tourists nonetheless still seek unmodernised ancient places such as Coleridge’s, or even Kublai Khan’s western capital, Xanadu without thought as to how the less wealthy local contemporaries may earn a livelihood there.

Wuzhen, like Lijiang, was dying. The silk industry had moved. Its homes were falling down, its canal was blocked and the bridges unsafe. China’s Big Project approach at Wuzhen to establish a vision and then a determination to complete a radical project rapidly is simply the Chinese way. The difficulties faced by China over the last two hundred years has left so much of their historical infrastructure in near total decay that there was no alternative.

Certainly the Cambridge University option of a constant series of tiny re-building projects did not exist. Where Wuzhen stands along the scale between recreation and restoration does not matter. It has been transformed and the architects of its revival deserve immense praise.

The Wuzhen experience also involves learning through direct involvement.

In the museums there are staff who will teach a child to weave straw, or mould small pieces of plastic into shapes. The museum of silk makes it clear how this wonderful fabric is made, dyed and woven.A large area of vegetable crops are grown, and a menagerie of animals tended in order to educate the hamburger eating young. The restoration of the town paired with learning opportunities in the museum, the theatre festival and the focus on the internet has certainly a proved successful combination.

Judged by the numbers visiting, by the monetary valuation of the Wuzhen company shares and by its aesthetics the project has been a triumph. It is estimated in 2017 that 300 million Chinese, twenty per cent of the population, have the funds and the wish to travel abroad. This number will grow. In the 1800s, given the absence of mutual trade, the English had to pay for its silk, tea and porcelain in silver. In consequence it created the vile opium trade. China too must seek to divert as many as possible of its people towards domestic tourism to avoid losing its own ‘ silver’. Wuzhen will play a role within this national imperative. It has already demonstrated the Chinese talent for transformational projects.