The Porcelain in Tang Dynasty

4 min readMuch progress must have been made in the ceramic production of the province of Jiangxi. It is recorded in the topography of Fuliang, referred to above, that in the beginning of the reign of the founder of the Tang Dynasty, a native of the district brought up a quantity of porcelain to the capital in Shaanxi, which he presented to the emperor as “imitation jade”. In the fourth year (622 C.E.) of this reign, the name of the district was changed to Xinpin, and a decree was issued directing the potters to send up a regular supply of porcelain for the use of the imperial palace.

The simile of “imitation jade” is significant and almost proves that it must have been genuine porcelain. White jade has always been the ideal of the Chinese potter, whose finished work actually rivals the most highly polished nephrite in purity of colour, translucency and lustre, while the egg-shell body attains the same degree of hardness (6.5 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness), so it can be scratched by a quartz crystal but not by the point of a steel knife. There are abundant references to porcelain in the voluminous literature of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The official biography of Chu Sui in the annals recounts the zeal that he showed while superintendent of Xinpin, obeying a decree issued in 707 ordering sacrificial utensils for the imperial tombs.

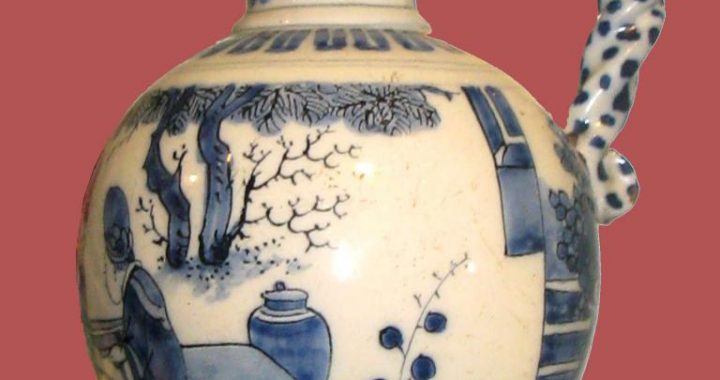

The Classic of Tea, the first volume in history devoted entirely to tea, describes the different kinds of bowls preferred by tea drinkers, classifying them according to the colour of their glaze and describing how each hue enhances the tint of the infusion. The poets of the time liken their wine cups to “disks of thinnest ice”, “tilted lotus leaves floating down a stream” and white or green jade. A verse of the poet Du Mu (803-852) is often cited in reference to white porcelain from the province of Sichuan: “The porcelain of the Ta-yi kilns is light and yet strong. It rings with a low jade note and is famed throughout the city. The beautiful white bowls surpass hoar frost and snow.” The first line of this verse praises the fabric, the second the resonance of the tone, the third the purity of the white glaze. The bowls most highly esteemed for tea were the white bowls of the province of Zhili and the blue bowls of Zhejiang. They both rang with a clear musical note and are said to have been used by musicians, in sets of ten, to make chimes, being struck on the rims with little rods of ebony. Arab trade with China flourished during the 8th and 9th centuries, when Muslim colonies settled in Canton and other seaport towns.

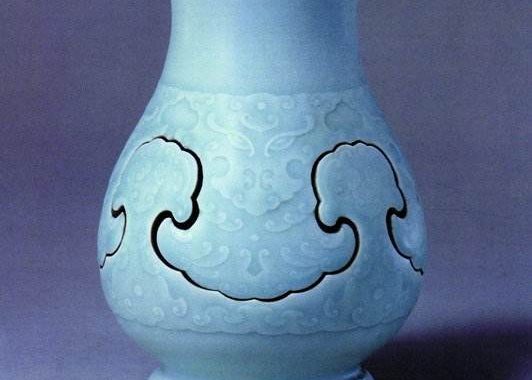

One of the Arabian travellers, Soleyman, wrote an account of his journey that has been translated into French and English, which gives the first mention of porcelain outside China. He says, “They have in China a very fine clay with which they make vases which are as transparent as glass; water is seen through them. These vases are made of clay”. The Arabs at this time were well acquainted with glass and could hardly have mistaken the material, so their evidence is of particular value. Under the Emperor Shizong (954-959) of the Later Zhou Dynasty, a brief regime established at Kaifeng just before the Song Dynasty, we have a glimpse of a celebrated production known afterwards as Chai yao, Chai being the name of the reigning house. The porcelain was ordered at this time by imperial prescript to be “as blue as the sky, as clear as a mirror, as thin as paper and as resonant as a musical stone of jade”. This eclipsed in its delicacy all that preceded it and soon became so rare that it was described as a myth. The various delicate wares referred to in the above extracts have all probably long since disappeared and we must be content with literary evidence of their existence.

The Chinese delight in literary research, as much as they fear to disturb the rest of the dead by digging in the ground, so that we have no tangible proof, so far, of the occurrence of true porcelain, and can only hope for the future appearance of an actual specimen of early date. Meanwhile we may reasonably accept the conclusion of the best native scholarship that porcelain was first made in the Han dynasty, without trying to fix the precise date of its invention.

A correct classification of Chinese porcelain should be primarily chronological, and the specimens should be secondarily grouped under the headings of the localities at which they were produced. Thirdly, each group may be subdivided, if necessary, according to the fabric, technique, and style of decoration of the pieces of which it is composed.