Tiger of Junction Street

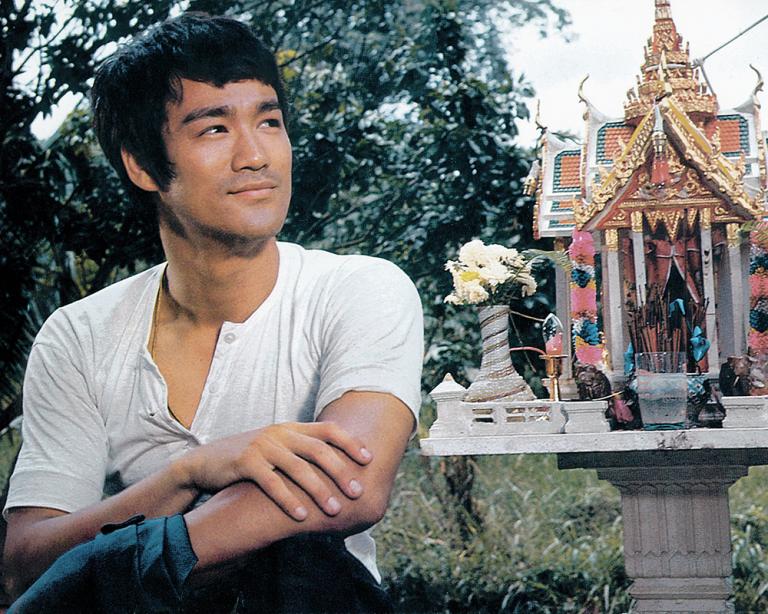

11 min readA year after beginning kung fu Bruce Lee took up dancing the cha-cha, mainly because of his interest in his partner Pearl Cho, although it also served to develop his balance and footwork. Unable to do anything by halves, Bruce kept a list of over a hundred different dance steps on a card in his wallet.

Along with fellow wing chun student Victor Kan, Bruce spent many evenings at the Champagne nightclub at Tsimshatsui, where they went to dance and admire the talents of the resident singer Miss Fong Yat Wah. A sharp dresser, Bruce insisted on ironing his own clothes. As he left the apartment each evening, he paused for a moment in front of the mirror to check his hair and flash the confident smile that never failed to charm the girls. His first serious girlfriend was Amy Chan, who later became famous in the East as film actress Pak Yan. Whenever Bruce had any money he would take her dancing, and on their dates, he would by turns make her laugh hysterically and scream with frustration. In private, she found him to be a good-hearted person who was always willing to help his friends, but as soon as they were joined by anyone else, Bruce turned into a chauvinistic show- off. Hawkins Cheung had also begun training with Yip Man in 1953 and he and Bruce soon struck up a friendship.

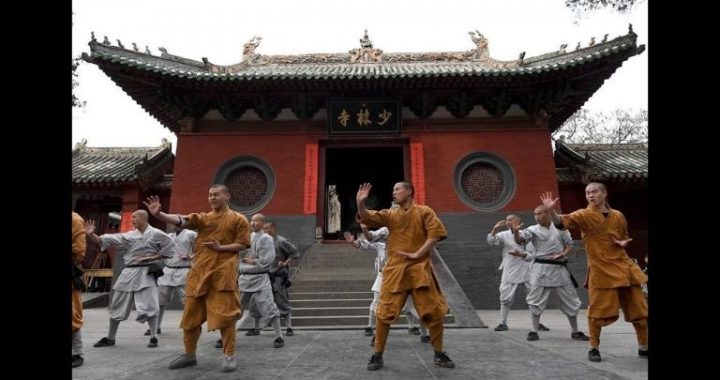

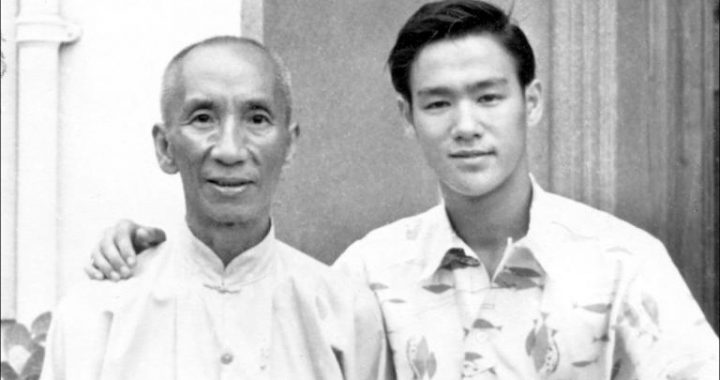

Speaking to Inside Kung Fu magazine, Cheung recalls: We started learning wing chun because of its reputation against other systems. But while learning the first form we felt frustrated. We said, ‘Why do you have to learn this? How can you fight like this?’ Everyonewanted to learn it quickly so that they could move on to the sticking hands exercises. The single sticking hands exercise was no fun and the younger students wanted to get through that even quicker. When we finally got to the double sticking hands exercise, we thought, ‘I can fight now!’ If you could land a punch on an opponent you felt proud and excited. ‘I can beat him now,’ was the first thought. That was our character – everyone wanted to beat his partner first and be top dog. Egos ran wild and everyone wanted to be the best. The Old Man always told us, ‘Relax! Relax! Don’t get excited!’ But whenever I practiced chi sao with someone, it was hard to relax: I became angry when struck and wanted to kill my opponent. When I saw Yip Man stick hands with others, he was very relaxed and even talked to his partner. Sometimes he threw his partner out without having to hit him. When I did sticking hands with Yip Man, I felt my balance being controlled by him when I attempted to strike. I was always off balance, with my toes or my heels off the ground.

I felt my hands rebound when I tried to strike him, as if he used my force to hit me, yet his movement was so slight, he didn’t seem to do anything, it was not a violent movement. When I asked him how he did it, he said, ‘Like this,’ and he demonstrated the movement which was the same as the practice form. Bruce Lee was going through the same experience: trying to master a physical technique, while confronting emotions like fear and anger, and rigid mental attitudes. The challenge was to persevere. He wanted to learn how to fight and he found it hard to follow Yip Man’s advice, which was to practise the form often and do it more slowly. Yip Man even suggested that Bruce stop doing sticking hands at all for a while. Bruce still wasn’t secure about his new skills and often used to carry a concealed blade or steel toilet chain as a weapon, although he didn’t use them often. Most of his street fights involved ripped clothes and bloody noses from blows landed by hands and feet. Leung Pak Chun, who was one of the Tigers, says: One day one of us was beaten up by a gang from Kowloon. Bruce and the others went off to get revenge. At first, Bruce approached them as if to talk it over, but when he got close enough to the two biggest ones, he hit them without warning.

These two turned out to be the family of a local Triad and WilliamCheung’s father, a high-ranking policeman, had to step in and mediate to prevent trouble escalating. Bruce’s sister Agnes says, ‘He began to get into more and more fights for no reason at all. And if he didn’t win, he was furious. Losing, even once in a while, was unbearable for him.’ ‘You never had to ask Bruce twice about a fight,’ said his younger brother Robert. Part of the responsibility for this also lay with Yip Man who, besides teaching relaxation and calmness, advised his students not to take everything on trust but to go out and test the system. Despite Bruce’s innate aggression, the seeds of understanding were beginning to take root, and a there was a depth of questioning that went beyond the brashness of his youth. Bruce even surprised himself by taking Yip Man’s advice to stop training for a while and spend some time contemplating the principles his teacher was trying to instil in him. Why was form so important? And what did that have to do with flowing with the events around him? As he would do throughout his life, whenever Bruce wanted to calm his fiery nature and reflect, he would walk by the water or through the rain. Now he spent time walking beside the harbour, as far away from the city’s bustle as he could get. Thinking about it over and over was no use – that would just drive you crazy. Suppose he could grow an extra head; would that increase his capacity to understand? No, it was a matter of using the form he already had more efficiently. Would he be a better fighter if he had four arms and four legs? If there were humans like that, he thought, then perhaps there might be another way of fighting! As he stood at the water’s edge, Bruce’s thoughts turned to the fish swimming in the deep as the possibility of a new way of approaching things dawned on him. Just as the reflections of clouds passed across the surface of the water, so he was able to see his own thoughts and feelings pass across his awareness. He wasn’t without feelings or thoughts but somehow, here, now, he wasn’t so bound up in them. The real challenge was whether he could find this sense of self when he was fighting and when more powerful emotions were involved. Bruce leaned down over the water and punched at his reflection.

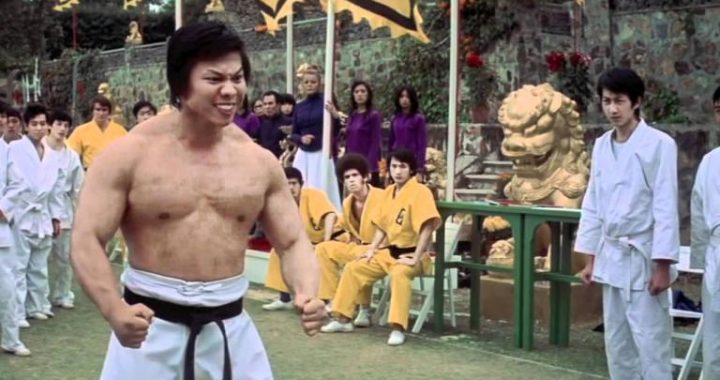

For a moment the water yielded to the force, parting and splashing away, but the instant he withdrew his hand, the water flowed back into the gap. As the reflected image took shape again, his face smiled gently. Nature had taught him something, not only about itself but about his own nature.And right at that moment there was no separation between the two. Bruce was soon to experience a new kind of conflict. When jealous juniors found out that he had German ancestors, they put pressure on Yip Man to stop teaching him, knowing that Yip was a staunch traditionalist who believed the art should never be taught to Westerners. Yip Man’s affection for Bruce and respect for his efforts caused him to refuse the other students’ demands. Soon people threatened to leave the school and no one would train with Bruce, so he left of his own accord. At first he trained with one of Yip Man’s senior students, Wong Sheung Leung, and sometimes he would intercept Wong’s other students and tell them their teacher was sick and there was no class that day, so they would go home and he would gain some private instruction. At St Francis Xavier some of Bruce’s restless energy was channelled by a teacher called Brother Edward, who encouraged Bruce to enter the 1958 Boxing Championships, which were held between twelve Hong Kong schools. Brother Edward, an ex-boxer himself, says of Bruce, ‘He was tough but he wasn’t a bully as some people think.’ Bruce used to train for the approaching contest every weekend with William Cheung, and by sheer force and determination he blasted his way through the preliminaries, leaving three opponents knocked out in the first round. In the final he faced an English boy, Gary Elms – from rival school, King George V – who had held the title for the past three years. In the ring, Elms had a classical boxing style. Bruce got into trouble almost immediately, and under some pressure in the corner he began swinging wildly. Despite the fact that boxing gloves are not the best aid to the trapping skills of wing chun, Bruce began to use some of the blocks he’d learned and countered with the continuous punching and two-level hitting he’d been working on. He was pleased enough with his third round knockout win to note it in the fight diary he kept. Meanwhile, the street fights continued, along with contests against other schools, and Bruce’s mother had to make frequent visits to the police station. In one such fight, the wing chun students fought the choy li fut students on the roof of an apartment building on Union Road in Kowloon.

According to Wong Sheun Leung it was Bruce who made the challenge. Wong recalls him as a hot-head who often caused trouble and showed no respect for the seniors of other styles, though he insists he wasn’t the delinquent some have portrayed him to be.Bruce’s fight was set to last two rounds, each two minutes long, with Wong as the referee. The fighters took up their positions and almost immediately Bruce’s opponent, a boy named Chung, attacked with a punch that Bruce palmed away. The next punch caught Bruce in the eye, shaking him up, and he reacted with a flurry of punches that fell short. He closed the distance but his blows were too wild and he was again hit on the nose and cheek. At the end of the first round Bruce sat in his corner, somewhat discouraged; his eye was swelling, his nose was bleeding and he hadn’t managed to land a single effective strike of his own. Bruce told Wong that he wanted to quit, worried that he wouldn’t be able to hide his injuries from his father, but Wong persuaded him to go on. As the second round opened, Bruce steadied himself and took a more determined stance, then feinted a couple of times and scored a straight punch to Chung’s face. As Chung gave ground, Bruce pursued him, hitting him repeatedly until he went down and others intervened. Bruce was elated and held his arms aloft. The victim’s parents went straight to the police and Mrs Lee was obliged to sign a paper promising to take responsibility for Bruce’s good conduct. Bruce had managed to stay in school largely by coercing other pupils to do his homework for him. Realizing that he stood more of a chance of going to jail than college, Grace Lee suggested that Bruce claim his right to American citizenship before the option lapsed on his eighteenth birthday.

At first Bruce wasn’t keen on the idea of emigrating, but his father rapidly warmed to it. Bruce told Hawkins Cheung that he was going to the US to become a dentist, but said he intended to earn money by teaching kung fu. Cheung reminded him that he only knew wing chun up to the second form, along with forty of the movements on the wooden dummy. Despite this, Bruce considered himself to be the sixth-best exponent in their style, but he took note of Cheung’s comments and felt it might be a good idea to have a few showy moves under his belt before he left. To learn these he went to see a man called Uncle Siu, who taught northern styles of kung fu. Bruce took Siu to a local coffee shop and struck a deal with him: over the following month Siu would teach him some of his moves, and in return Bruce would give Siu dancing lessons. They began at seven one morning, with Siu leading Bruce through two northern-style kung fu forms, a praying mantis form and another called jeet kune or ‘quick fist’. But Siu got the worst of the deal. He expected Bruce to take three or four weeks to learn the forms but Bruce mastered themin just three days, before Siu even got going with the basic cha-cha steps. Bruce had retained his friendship with Unicorn throughout their youth and they both became child actors. The two appeared together in Bruce’s first full-length film The Birth of Mankind, with Unicorn playing a shoeshine boy and Bruce a street rascal who fought with him. Run Run Shaw, the head of the Shaw Brothers studio, which employed Unicorn, now asked Bruce to sign a contract with them. Bruce told his mother he wanted to accept the offer, but Grace Lee somehow managed to persuade him that his best chance of making something of his life would come from finishing his education in the US. But before he left he managed to become the Crown Colony Cha-Cha Champion of 1958. Prior to leaving Hong Kong, Bruce had to apply to the local police station for a certificate to clear him for emigration. There he found that both he and Hawkins Cheung were on a blacklist of local troublemakers. Over- dramatizing the issue, Bruce phoned his friend, ‘We’re on a known gangster list,’ he said. ‘I’ve got to clear my name, and while I’m there, I’ll clear yours too.’ Whatever efforts Bruce made, however, resulted, a few days later, in a policeman calling at the Cheung household to ask questions about ‘gang relations’. Rather than settling matters, he’d succeeded in stirring up even more trouble. In the end Mr Cheung Senior had to pay to have his son’s name wiped from the record, so he could go to Australia to attend college. The day before Bruce left for America, he went to say goodbye to Unicorn. He told his friend he felt his father and his family didn’t love him or respect him. He felt that he had to achieve something in life, conceding that his mother was right, and if he didn’t take this opportunity, he might end up in real trouble. Bruce’s younger brother Robert recalls, ‘One evening Bruce came to my room with a suitcase in his hand. He put the case down and for a moment looked at me with a sad expression. He didn’t say anything, then he picked up the case, turned and left. I guess that was his way of saying goodbye.’ As he was leaving, Bruce’s mother slipped a hundred dollars into his pocket, while his father gave him fifteen. Bruce picked up his bags, but as he left the room his father called him back. As Bruce returned, his father suddenly waved him away again: he was enacting a Chinese tradition. Because he had made this gesture, even though his son was going far away,he would return to attend the father’s funeral. Quietly and a little disappointed, Bruce picked up his bags and continued on his way.