Way of the Dragon

19 min readBruce Lee had made two successful films in the East, but his ambitions still lay in the West. Even as he planned his third film, he anxiously awaited a decision from Warners and the ABC network about The Warrior. He wanted the part desperately and had set his mind on it so much that he told both his friends and the local press that matters were virtually settled. However, towards the end of 1971, an interview he did for Canadian TV indicated that things weren’t going his way at all.

The Canadian news reporter Pierre Berton, who was one of the first in the West to realize the new phenomenon that was Bruce Lee, flew to Hong Kong to interview Bruce. Berton: Are you going to stay in Hong Kong and be famous, or are you going to the United States to be famous? Bruce: I’m gonna do both. Because I have already made up my mind that in the United States, I think something of the Oriental, I mean the true Oriental, should be shown. Berton: Hollywood sure as heck hasn’t. Bruce: You better believe it man. I mean it’s always the pigtail and the bouncing around, chop- chop, you know, with the eyes slanted and all that. Berton: Let me ask you about the problems that you face as a Chinese hero in an American series. Have people come up to you in the industry and said, ‘Well, we don’t know how the audience is going to take a non-American’? Bruce: Well, the question has been raised. In fact, it is being discussed, and that is why The Warrior is probably not going to be on . . . They think, businesswise, it’s a risk. And I don’t blame them . . . If I were the man with the money I would probably have my own worry whether or not the acceptance would be there. Berton: How about the other side of the coin: is it possible that you are – well, you’re fairly hip and fairly Americanized – are you too Western for Oriental audiences? Bruce: I have been criticized for that. On 7 December 1971, Bruce received a telegram from Warners saying that‘due to pressures from the network regarding casting’ he had been dropped from The Warrior TV series, which had by now been renamed Kung Fu. In his 1993 book The Kung Fu Book of Caine: The Complete Guide to TV’s First Mystical Eastern Western, Herbie Pilato writes about the casting history for the series: Before the filming of the Kung Fu TV movie began, there was some discussion as to whether or not an Asian actor should play Kwai Chang Caine. Bruce Lee’s name was put forward for the role. But in 1971, Bruce Lee wasn’t the cult film hero he later became for his roles in Fists of Fury and Enter the Dragon. At that point he was best known as Kato on TV’s Green Hornet. ‘In my eyes and in the eyes of Jerry Thorpe [director],’ said Harvey Frand [production supervisor], ‘David Carradine was always our first choice to play Caine. But there was some disagreement because the network was interested in a more muscular actor and the studio was interested in getting Bruce Lee.’ Frand says Lee wouldn’t have really been appropriate for the series, despite the fact that he went on to considerable success in the martial arts film world. The Kung Fu show needed a serene person, and Carradine was more appropriate for the role. Ed Spielman [scriptwriter] agrees: ‘I liked David in the part. One of Japan’s foremost karate champions used to say that the only qualification that was needed to be trained in the martial arts was that you had to know how to dance. And on top of being an accomplished athlete and actor, David could dance . . . The character was half-Asian and half-Caucasian, so either an Asian or a Caucasian would have been a reasonable choice; a Eurasian would have been the most natural choice.

Many of these later comments by those involved have more than a hint of retrospective justification. For the record, Bruce Lee’s mother was half- German and he was the 1957 Cha-Cha Champion of Hong Kong, making him in fact a Eurasian dancer – although hardly a ‘serene’ one! But as one senior TV executive at Warners later admitted, although they knew he wanted the role, Bruce Lee was never seriously considered. Before taking the role of Caine, David Carradine openly admitted he had only heard the expression ‘kung fu’ twice and had certainly never practised the art. Yet he confidently asserted that ‘No one on the planet was more prepared on as many levels to play the role of Caine as I was.’ In fact, most of the early action from the series features judo moves allied to Jewish Torah philosophy, because the technical advisor, David Chow, also knew little about kung fu, and its writers knew little about Taoism. Eventually a new technical director, Kam Yuen, was brought in. On 22 February 1972, ABC TV’s Movie of the Week was the pilot for the Kung Fu series. The accompanying press release explained the theme: ‘Kwai Chang Caine, a Chinese-American fugitive from a murder charge in Imperial China, becomes a superhero to the coolies building the transcontinental railroad through his mastery of an ancient science-religion.’On 8 August 1972, due to public demand the Kung Fu pilot was repeated following thousands of letters flooding into the production office. It became a weekly series in January 1973 and quickly became the number-one TV show in the US. Joe Lewis, the karate champion who trained with Bruce Lee, recalls Bruce’s own idea for the opening of what became the Kung Fu series: a Chinese- looking stagecoach with lots of ornamentation pulls into a dusty main street. As all the local cowboys amble up to look it over, the doors fly open, and out jumps a man in a kung fu suit. Lewis says that when Warners gave the part to David Carradine, Bruce decided he would concentrate on Hong Kong to begin his climb to success, just as Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson had gone to Europe to become stars first. Lewis adds, ‘It hurt Bruce when he failed to get the Kung Fu series. He experienced a lot of rejection.’ Bruce Lee had been thinking about writing and directing long before he went to Hong Kong to make his first film for Golden Harvest. Joe Lewis says that during the time he and Chuck Norris were training with Bruce, he would often mention ideas for films. Although Joe and Bruce worked together when Bruce choreographed the fights for The Wrecking Crew, Lewis declined to get involved in Bruce’s new venture. He felt that in this film, Bruce was aiming to show that the Asian martial artist was superior to the Caucasian. Lewis claims that Bruce wanted to cast him as ‘a big, strong, muscular, blue-eyed, blond-haired, all-American punch bag’. But Bruce countered that the problem was finding Western martial artists – who almost always had a bigger physique – who were fast enough to fight him convincingly. Bruce said that he asked Chuck Norris to appear in Way of the Dragon because Norris was one of the few Western martial artists who was fast enough.

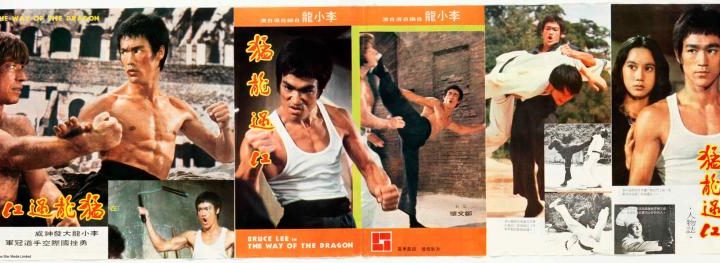

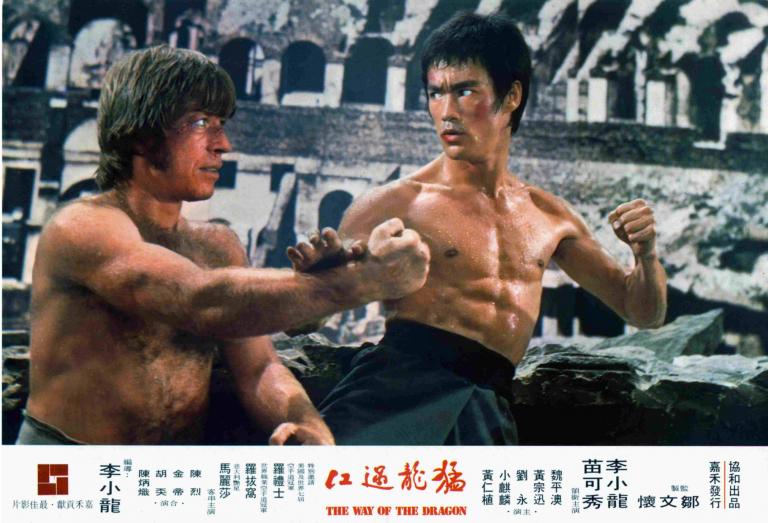

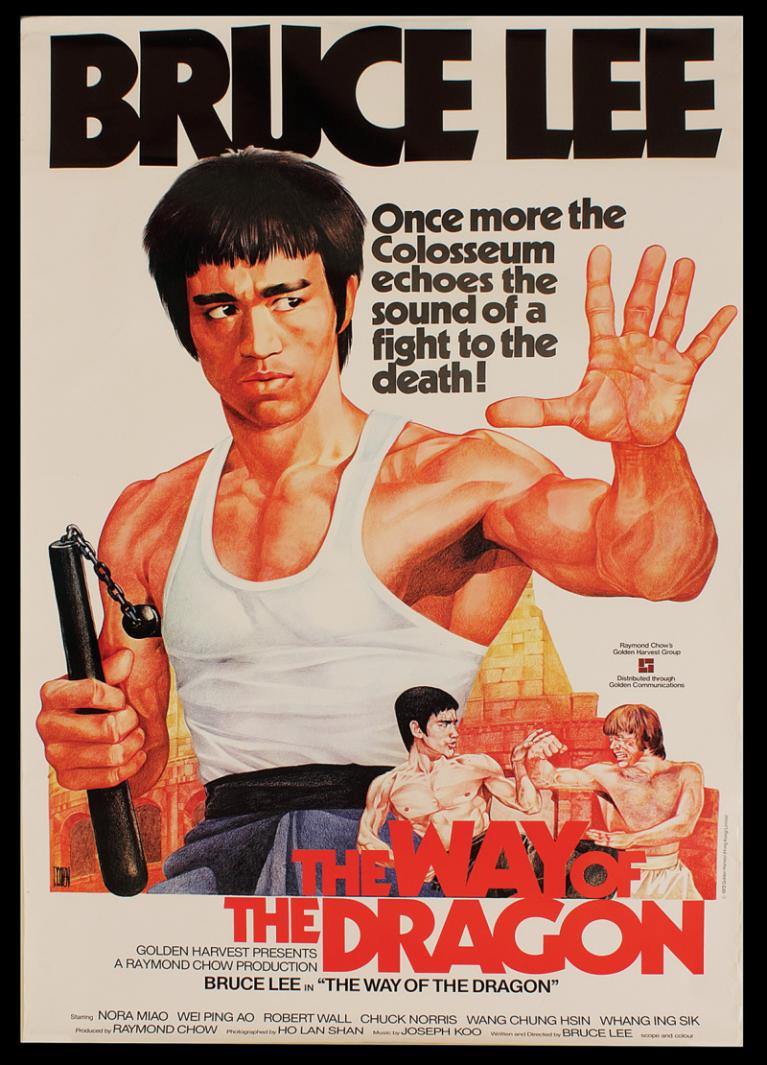

Bruce commented that he’d worked on his own speed because a smaller man who can swing faster hits as hard as a heavier man who swings slowly. ‘And besides,’ he added, ‘you can’t keep fighting midgets.’ Joe Lewis obviously felt that the power of the stronger, heavier Western martial artist would ultimately prevail over the speed of the faster, lighter Asian martial artist and that’s why he declined to act to the contrary. Lewis continues, ‘Bruce knew that he was asking me to get involved in a movie where I got my butt beat by a little 128-pound Chinese guy who’d never been in the ring.’ A succinct comment from Bruce’s mother shows that Joe wasn’t far off themark. Grace Lee recalls, ‘Bruce told me: “Mom, I’m an Oriental person, therefore I have to defeat all the whites in the film.” I don’t believe he ever mentioned this to Chuck Norris.’ However, Bruce had mentioned this to Chuck Norris, who recalls: In 1972, Bruce was directing Way of the Dragon and wanted me to be in it. ‘I want you to be my opponent,’ Bruce said with excitement. ‘We’ll have a fight in the Coliseum in Rome – two gladiators in a fight to the death. Best of all, we can choreograph it ourselves. I promise you the fight will be the highlight of the film.’ ‘Great,’ I said, ‘who wins?’ ‘I do,’ Bruce said with a laugh, ‘I’m the star!’ ‘Oh? You’re going to beat up the current world karate champion?’ ‘No,’ said Bruce, ‘I’m going to kill the current world karate champion!’ I laughed and agreed to do the movie after gaining twenty pounds, at his request, because he wanted me to look more formidable as his opponent. In early 1972, in preparation for filming Way of the Dragon, Bruce Lee bought and read a dozen books dealing with all aspects of filmmaking. Placing incredible demands on his energy, he intended virtually to make the entire picture himself: to write, produce, direct and star in it; to scout the locations, cast it, choose the wardrobe and choreograph the fight scenes. In the process he lost several pounds of hard-won weight. For the storyline, Bruce drew on his memories of leaving Hong Kong for San Francisco in 1958, and on his experiences as a waiter at Ruby Chow’s restaurant. When he’d first arrived in the US, Bruce had bought a Chinese- English dictionary; but he now found himself referring to it to find the appropriate Chinese words, rather than English ones, so that he could express his ideas when planning meetings with his assistants. Way of the Dragon was the first Hong Kong-based picture to be shot in Europe. At $130,000, the budget was slightly higher than his previous films, but production costs were already covered by pre-sales to Taiwan. On 4 May 1972, the first team arrived in Rome. It consisted of Bruce, Raymond Chow and Nishimoto Tadashi, a Japanese cameraman Bruce hired because he considered the Japanese to have more technical expertise. Leading actress Nora Miao, along with other members of cast and crew, arrived three days later, after spending nineteen hours on a plane routed via Thailand, India and Israel. Bruce let the crew rest for a couple of days, but when shooting started on 10 May, he proved to be a demanding director who expected the same level of commitment from everyone else as he was prepared to invest himself. Inthe following days they buzzed around Rome, pausing to film illegally at the Colosseum. At the Trevi fountain, they stayed long enough for Bruce to throw a coin in the water and make a wish. It’s not hard to imagine what it was.

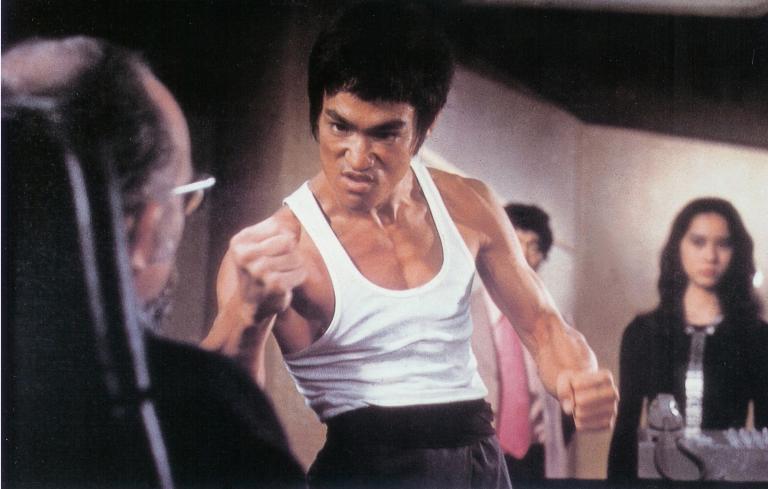

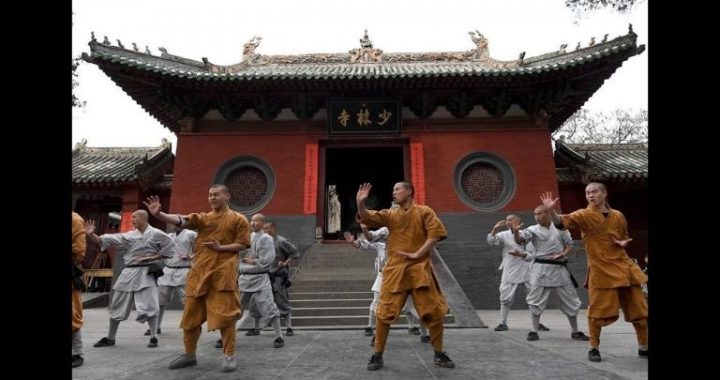

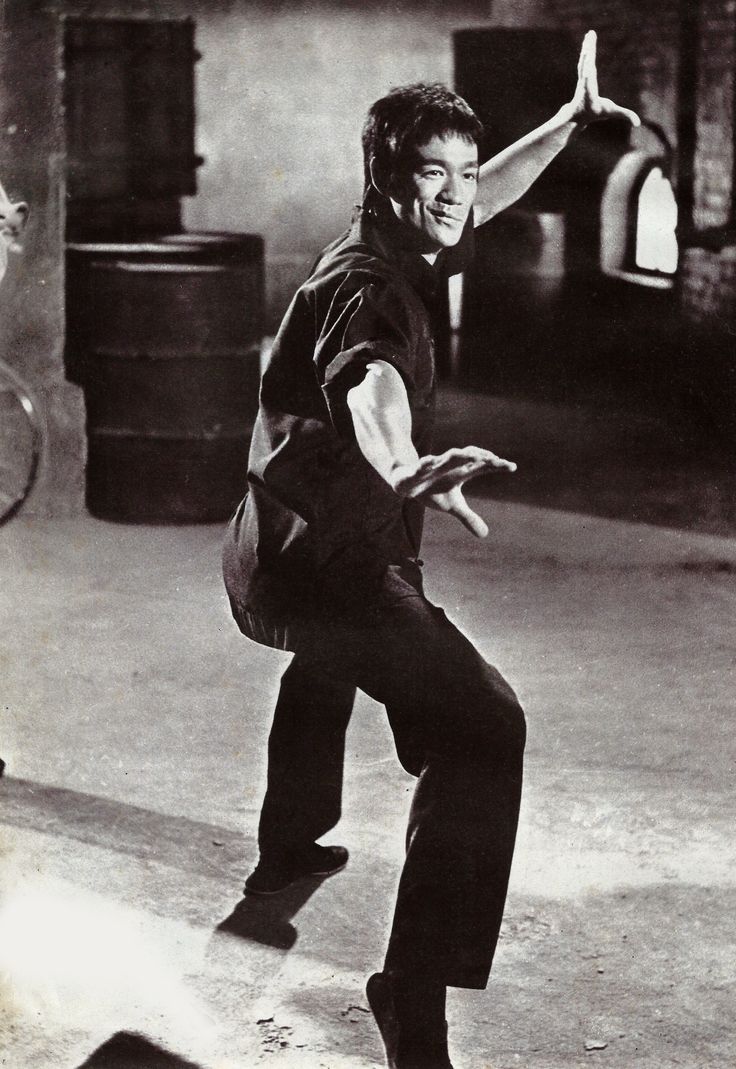

Having shot the location set-ups, Bruce could now turn his attention to more important matters: the fight scenes. Knowing how it would look on camera, Bruce spent a lot of time teaching his co-actors how to react convincingly. In contrast to the speed at which he’d hounded everyone around Rome, shooting over sixty scenes in one day alone, he then spent over forty-five hours on his fight scene with Chuck Norris. Bruce’s choreographed directions for this scene took up nearly a quarter of the script. As with all the fight scenes, Bruce watched the daily rushes, and if he saw any unconvincing moment of action, the whole scene would have to be re-shot. By the time the film wrapped, Bruce had been involved in yet another aspect of filmmaking: he played percussion on the music for the soundtrack. In the film Bruce plays a country bumpkin named Tang Lung (China Dragon) who leaves Hong Kong and goes to Rome. While waiting to be met at the airport he goes into a restaurant where, due to problems with the language, he finds he has mistakenly ordered four plates of soup. Tang is later met by his cousin, played by Nora Miao, and as they drive to her apartment, she explains that she has inherited a restaurant on some property wanted by the mob. In the scene itself the story is more concerned with Tang’s need to find a toilet, something that had them rolling in the aisles in Hong Kong. Way of the Dragon is played as a comedy, with pauses to accommodate audience laughter and a soundtrack punctuated with comic ‘wah-wah’ sounds and ‘boings’ from the timpani. Yet, for all that, it features some outstanding fight scenes and one or two excellent kung fu lessons. All the waiters in the restaurant are learning karate in order to repel the thugs who are harassing them and driving away the restaurant’s customers. Tang attends a training session at the back of the premises, where one of the waiters – Bruce’s old friend Unicorn – is drilling the others – including Bruce’s adopted brother, Wu Ngan. An argument starts about the merits of the various fighting systems. ‘It doesn’t matter where it comes from,’ says Tang, ‘you can learn to use it.’ Later, when the thugs return to intimidate the customers, Tang does battle with them outside. The waiters are so impressed with what they see that they vow to give up karate and learn Chinese fighting.A further confrontation between Bruce and the thugs is played for laughs, but it contains some superb fight sequences, especially those featuring Bruce using the nunchakas. The weapon’s potential for being more dangerous to an inept user than to his opponent is a comic possibility seized on by Bruce.

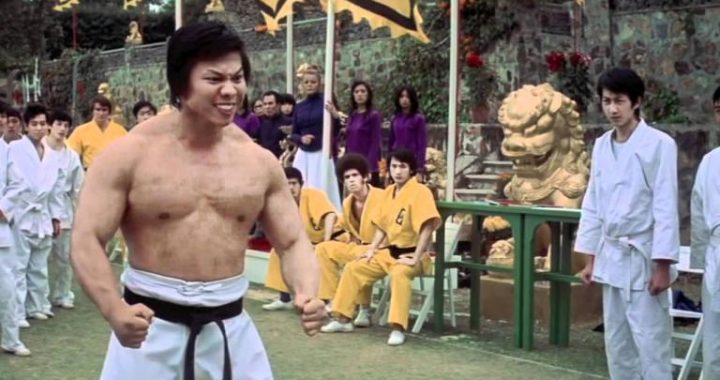

One of the Italian hoods manages to grab a pair and having seen Tang wielding them with nonchalant grace, he believes he too is imbued with the supernatural power of an Excalibur, but as he goes to strike Tang, he knocks himself out. No matter how skilled a martial artist is, however, he can’t beat a bullet, which is why kung fu movies were more credible in the East than in the US and Europe, because the martial arts tradition in places like Hong Kong and Singapore was intertwined with the British custom – at the time – of having mainly unarmed police. Likewise, most of the population were similarly unarmed, because there was no access to guns and most people couldn’t afford them. Men fought with their bodies, hand-to-hand, or used traditional and makeshift weapons. In Way of the Dragon Bruce had the gangsters carry guns and attempted to confront the problem by having Tang carve poison darts, which he fires with unerring accuracy into the gangsters’ gun hands, just as Kato had done in the first episode of The Green Hornet. These sequences do no more to overcome the major drawback of the martial arts genre than any other attempt and are the most unlikely scenes of the film, though the action that follows more than compensates. Once Tang has dispatched the local heavies, the Godfather has to import hired fighters played by Wong In Sik, a Korean hapkido exponent, and karate stars Bob Wall and Chuck Norris. In the Western version of the film, Norris’s character is named Colt. By offering a truce, the gang lures Tang into a trap. The first two opponents are dealt with, then in a sudden shift of scene from the countryside to the centre of Rome, the final scene is fought out under the arches of the Colosseum. Tang and his ultimate Anglo-Saxon enemy, Colt, face each other with all the dignity and formality of two samurai warriors; their only spectator a tiny kitten. Again there are comic moments, such as when Tang rips a handful of hair from Colt’s chest, but this fight scene is the best that Bruce Lee ever committed to film. In it Bruce was anxious not to make the fight a completely one-sided affair, but there was never any doubt as to what the outcome would be. In the first half of the screen fight, it is Colt who has the upper hand,knocking Tang to the floor a couple of times and bloodying his mouth. The turning point comes when Tang bounces back, dancing and moving like Muhammad Ali, bewildering Colt. As Tang speeds up the cadence of his footwork Colt follows him, not realizing that Tang has regained the initiative and is now dictating the pace. In one sequence Bruce Lee overwhelms Chuck Norris with a cluster of punches that are almost too quick to count. It’s a sequence taken directly from Muhammad Ali’s fight with Cleveland Williams, which Bruce studied over and over again on his home movie projector. It’s even shot from exactly the same camera angles. In the ensuing action, Tang delivers a devastatingly fast combination of strikes as he begins to overwhelm Colt, who sustains a broken arm and leg but struggles to his feet to continue the fight. Tang glances down at Colt’s broken leg and shakes his head, as if to say, ‘Look, you’ve got nothing to prove. Stop this while you can.’ But Colt’s warrior code leaves him only two options: victory or death. Colt almost smiles in acceptance of his fate, then attacks with one last flurry of blows until in the final exchange Tang breaks Colt’s neck.

At this moment a strange expression of remorse spreads over Tang’s face, then he lowers Colt’s body to the ground and respectfully places Colt’s jacket and black belt over his body. In beating Norris in the Western world’s greatest historical arena, Bruce Lee was once again giving his audience what they wanted to see, but he was also aware of the sentiments he was stirring and sought to include other lessons. The way he honours the opponent he has just killed is also in accordance with one of the tenets of the warrior’s code: that a worthy opponent be treated with respect. Bruce Lee told his friends that Way of the Dragon would be a hit on the Mandarin circuit but that he had no plans to release it in the West. The humour, which had Eastern audiences convulsed with laughter, would be missed in the West. The ‘soup scene’ was a big hit in the East because Campbell’s had recently begun importing their soups there and indigestion from this unfamiliar food was common. Bruce’s script was based on a real understanding of the Chinese psyche. Bruce’s character in the film has a much softer persona, with his hair brushed down and pointed sideburns that gives him an almost elfin look, but he slowly strips this character of his superficial naivety to reveal the capable hero at heart. To a chorus of disbelief from the Hong Kong press, Bruce predicted thatthe picture would earn $HK5 million. Shaking their heads in amazement, journalists also showed some irritation. They were no longer interested in celebrating the success of Bruce Lee, they were looking for flaws, so while dutifully reporting the new milestone in Bruce’s career, the press began speculating about who he might be sleeping with. In August 1972, Miss Pang Cheng Lian, a reporter on New Nation, the English newspaper in Singapore, went to Hong Kong for a week to write four daily features based on interviews with Bruce Lee. She spent time with him at the Golden Harvest studios where he was dubbing Way of the Dragon and there they had lunch together, after which Bruce made his customary call home. When he returned, Miss Pang brought up the subject of female martial artists. Bruce told her that a woman could never match a man for strength, so her best bet was to use her powers of seduction and persuasion to gain an opportunity to jab her assailant in the eyes or kick his groin before running like hell. With talk of seduction and vital parts, the questions turned to Bruce’s relationship with a certain actress. His response was that the people of Hong Kong had too much time to invent stories that would upset the girl in question, Betty Ting Pei. In 1967 Tang Mei Li changed her name to Betty Ting Pei and signed up as one of Run Run Shaw’s jobbing actresses. The ‘sultry Taiwanese sex bomb’ – as her publicity described her – had acted in around thirty films – dramas, comedies, musicals and martial arts films – though most often she played roles that ended up in the bedroom. The twenty-five-year-old rising starlet had yet to break through into leading roles when she and Bruce were introduced on the film set by Raymond Chow, and within days, Bruce told his friends, ‘She brightens up an otherwise dull film set. She quite makes my day.’ The Lee family now moved from the small apartment on Man Wan Road into one of the few two-storey detached houses in Hong Kong, at 41 Cumberland Road in the Kowloon Tong area. Although the large eleven-room house might have been considered average in Beverly Hills, in Hong Kong it was a palace. It had wrought-iron gates and an eight-foot stone wall enclosing a large Japanese garden where a stream wound through the trees to a goldfish pond spanned by an ornamental bridge, all of which could be viewed from the balcony of the main room, where Bruce had set up his new hi-fi system. Best of all, the house had enough space for a study to house his thousands ofbooks and a fully equipped gymnasium. Bruce replaced the red Porsche he’d given up in Los Angeles with a new red Mercedes 350 SL, most likely the same one seen in the closing shots of Way of the Dragon. And in response to Bruce’s taste for silk suits and even a fur coat, the press duly voted him ‘Worst-Dressed Actor of the Year’.

The move to their new house happened just in time, and it became Bruce’s sanctuary and the only place he could enjoy some peace and privacy. A few years before he had put on impromptu displays of kung fu at dances, doing one-finger push-ups to attract an audience. Now he couldn’t visit a restaurant without having to sit at a corner table with his back to everyone, hoping not to be noticed. But once the waiters began to hover, there would soon be a queue of people demanding autographs and asking familiar questions, and by the time Bruce left the restaurant, he would be faced with a jostling crowd of paparazzi. What’s more, if he reacted badly to any of this, the next day’s headlines would report his arrogance and ill manners. Bruce’s fame was a double-edged sword, and he said he now understood why stars like Steve McQueen avoided public places and regretted that they could no longer lead a normal life. Yet, in recalling his earlier vow to be a bigger star than McQueen, Bruce couldn’t resist revelling in his celebrity. The pressure of sudden stardom may be an entertainment business cliché, but it is real enough. While it drives some to become recluses or surround themselves with bodyguards, in Bruce’s case another contradiction emerged. On the one hand he fed off the public’s response and the recognition he’d been trying for years to achieve, on the other he could no longer pursue his art in the way that had made all this possible. The paradox revealed itself at a party once where a guest failed to recognize him. With a healthy dose of self- mockery he extended his hand and announced, ‘Bruce Lee, movie star.’ The old money problems had eased, but new problems arose to take their place. Producers extended big offers, usually with maximum fanfare and minimum resources to back them up, simply as a way of increasing their own prestige and getting some free publicity. The China Star, a down-market Hong Kong daily, ran a series ‘written’ by Yip Chun, the son of Yip Man, who at one time had trained alongside Bruce. The article quoted Yip Chun as saying that he had seen Bruce knocked down by an opponent during training. While no one could expect Bruce to have been invincible from the age of thirteen, the tone of the article upset him enough for him to track down Yip Chun and ask if he’d really said what had been printed. Yip Chun denied it,claiming it was an extravagance on the part of the article’s ghostwriter, The Star’s boss, a hard-bitten Australian named Graham Jenkins, who duly reported that Bruce had threatened his paper’s contributor. Bruce began a legal action against the paper, only to find himself being followed everywhere by photographers and reporters wanting to hype up a sensation on the slightest pretext. What the media didn’t report were Bruce’s simple acts of consideration for others. Bob Wall offers an example: Both Bruce and I wore contact lenses and when we were fighting in the dust, in the Roman countryside, we kept getting choked up. Bruce had some really good eye lotion and we were able to get through our fight scenes by using it. Later, as I was about to board the plane back to the US, I saw a commotion outside the airport departure lounge where a crowd of people had gathered. Then I saw Bruce’s red Mercedes and a few moments later he appeared in the lounge. He’d driven out to the airport to give me a whole case of this eye lotion as a gift. Even with all the demands on his time, he’d taken the trouble to do that. Bruce Lee had never been motivated purely by matters of wealth or status. Bombarded with invitations both to present and accept various awards and trophies, he elected instead to spend the time studying or training.

Neither fame nor money was an end in itself, they were simply the by-products of him doing his work well. The biggest advantage of money was that it allowed him the autonomy to set his own standards. As a martial arts teacher, Bruce had maintained standards that prevented him from over-commercializing his art by opening a chain of ‘gung fu’ institutes that would have been connected to him in name only, and he sought to apply the same values to his films. It’s doubtful whether the producers who now hounded him would have understood the principles by which he tried to operate; they just wanted to lure him to their sets with promises of huge sums of money. Just as fame was a side-effect of being the best, so wealth would be the natural outcome of work done with commitment and attention. For Bruce, what remained important was the quality of one’s work, so a good studio carpenter could earn his respect more easily than a hack director like Lo Wei. In the slipstream of three successful films Bruce Lee now planned a new film, which would feature some of the world’s foremost martial artists, because he wanted to involve his friends and show his appreciation to them, both as teachers and students. Game of Death would be a crowning achievement.